On April 20, 1825, David Douglas (1799-1834) arrives at Fort Vancouver, the Hudson's Bay Company's new Columbia River headquarters, in the company of chief factor Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857). The young Scotsman is a collector for England's Horticultural Society, dispatched to the Northwest Coast to bring back specimens and seeds of the marvelous and new (to Europeans) plants of the region, for introduction into British gardens and forests. For the next two years, Douglas will use Fort Vancouver as a base for botanical explorations through much of present-day Washington and Oregon, where he will collect thousands of specimens of plants ranging from tiny, rare mosses and herbs to the giant and abundant tree that now bears his name, the Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzeisii, not actually a fir, but a member of a Pacific Rim genus).

A Scientific Traveler

David Douglas, the son of a Scottish stone mason, was an apprentice gardener in Glasgow when his educational ambition and enthusiasm for plant collecting brought him to the attention of William J. Hooker (1785-1865), a leading British botanist. Hooker recommended Douglas to the Horticultural Society (later the Royal Horticultural Society) as "an individual eminently calculated to do himself credit as a scientific traveler" (Nisbet, 7). At the turn of the nineteenth century, well-to-do landowners in Britain and elsewhere in Europe were fascinated by exotic flora from other parts of the world and sought new ornamental species for their gardens.

There was particular interest in the Northwest Coast of North America, first explored by Europeans (beginning with the Spanish) only a generation earlier. Archibald Menzies, the surgeon and naturalist who accompanied the 1792 expedition of Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver (1758-1798), brought back descriptions and dried specimens of many species -- including the Douglas fir -- but no seeds or living plants. The reports of the Lewis and Clark expedition and the specimens they introduced into American gardens heightened desire for more of the region's remarkable flora. After proving himself with a collecting trip in 1823 to the eastern United States and Canada, Douglas was chosen for the Northwest expedition.

Of necessity, the collecting journey was "undertaken under the protection of the Hudson's Bay Company" (Harvey, 41). The company's scattered fur trading outposts were the only non-Indian settlements in the vast region, and its logistical support was essential. In July 1824, Douglas sailed from England on the company ship William and Ann, which was making the annual supply run to the Columbia. Before departing, he studied the few existing scientific texts that described Northwest flora and met with Menzies and other scientists who had visited the area. The long voyage around Cape Horn and up the west coast of the Americas was followed by fierce storms that for seven weeks prevented the ship from entering the Columbia.

The Long Wished-for Spot

Finally on April 7, 1825, the William and Ann managed to cross the bar and anchor in Baker Bay, much to Douglas's relief. He wrote:

"The joy of viewing land, the hope of in a few days ranging through the long wished-for spot and the pleasure of again resuming my wonted employment may be readily calculated" (Journal, 102).

Constant heavy, cold rain kept Douglas on ship the following day, but on the 9th he landed at Cape Disappointment and made his first botanical observations:

"On stepping on the shore Gaultheria Shallon [salal] was the first plant I took in my hands. So pleased was I that I could scarcely see anything but it. Mr. Menzies correctly observes that it grows under thick [conifer] forests in great luxuriance and would make a valuable addition to our gardens" (Journal, 102).

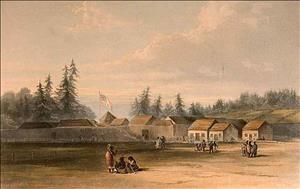

Two days later the ship reached Fort George, the Hudson's Bay Company post at what is now Astoria, Oregon, only to find that the company was moving operations to the new Fort Vancouver, which it had just opened on March 19 on the north (Washington) side of the river, about 100 miles above the mouth. Chief factor John McLoughlin came down from the new post to greet the ship. McLaughlin and Douglas traveled upriver in a canoe paddled by six Indians, who made the journey in two grueling days, reaching Fort Vancouver on the evening of April 20, 1825.

Since quarters were still being built, McLaughlin initially offered Douglas a tent for his residence. Later, "a lodge of deerskin was ... made for me which soon became too small by the augmenting of my collection" (Journal, 107). Eventually Douglas lived in a cedar bark hut.

Botanical Journeys

Douglas spent the rest of 1825 at Fort Vancouver, making collecting journeys of a few days or weeks up and down the Columbia, Willamette, Chehalis, and Cowlitz rivers and along the Washington coast. Although he concentrated on plants, Douglas also preserved some of the animals he hunted and collected geological samples. He sometimes traveled with Hudson's Bay employees, but often relied on local inhabitants to guide him. Douglas quickly learned the Chinook Jargon trade language and made friends in the Chinook villages of the lower Columbia who shared their knowledge of local plants and sent him seeds of plants he was interested in. By the end of the year, he had traveled (according to his probably generous estimates) 2,105 miles and amassed 510 separate plant specimens.

The following year, Douglas ranged more widely, estimating (again generously) that he traveled 3,932 miles. He spent much of the summer east of the Cascade Mountains, botanizing the dry, barren country of the Columbia Basin as diligently as he had the wet western forests. He ascended the Columbia as far as Kettle Falls and explored the Spokane and Snake rivers and the Blue Mountains of Oregon. In the fall, he joined a Hudson's Bay Company expedition to the Umpqua River in southwestern Oregon.

After another winter at Fort Vancouver, in 1827 Douglas traveled with the company "express" over the Canadian Rockies to Hudson Bay, where a company ship carried him to England. Many of his specimens, sent by ship from the Columbia, had already reached the Horticultural Society, and he was met with great acclaim. As a result of Douglas's collections, salal, red flowering currant, Oregon grape, and other Northwest plants soon populated gardens in England and eventually throughout the world. Douglas fir trees planted from seeds he collected still stand in England and Scotland. "Doug fir" and other trees Douglas introduced (which include the ponderosa, western white and other pines, several true firs, and the Sitka spruce) have become commercially important not only in their native habitat but in Great Britain and many other countries.

David Douglas made two more journeys to the Columbia River, in 1830 and in 1832-1833, before dying at the age of 34 under mysterious circumstances in Hawaii, trampled after apparently falling into a pit trap for wild cattle.