On August 31, 1999, the City of Sammamish formally incorporates. After a decade of wrangling, one failed vote for incorporation, and an unsuccessful attempt to annex to Issaquah, voters approved the incorporation of the City of Sammamish on November 3, 1998. The new municipality is carved out of an area in King County on the Sammamish Plateau just east of Lake Sammamish.

Early Years

The lands that would one day be known as the city of Sammamish were home to Native American tribes (such as the Snoqualmie) long before the first scattered non-Indian settlers began making tentative inroads onto the Sammamish Plateau in the 1870s and 1880s. By the late 1880s a few more settlers were starting to arrive, but it was the 1890s before people began arriving in real numbers. The southern half of the plateau, particularly the area near Pine Lake, developed (relatively speaking) more quickly than the northern half. By the late 1930s no less than three resorts (the Tanska Auto Camp and French’s LaPine Resort, both on Pine Lake, and the Four Seasons Resort on Beaver Lake) were operating on the southern half of the plateau.

The Sammamish Plateau’s country ambiance remained unchanged through the 1950s, with the area’s population probably edging above 1,000 for the first time during that decade. But in the 1960s, a small amount of development began creeping in; by 1970, all of the resorts were gone. Much of the rural feeling still remained in the 1970s even as the plateau’s population passed 5,000 early in the decade and steadily increased, particularly after 1975. Then, in the mid-1980s, growth accelerated dramatically as more homes, schools, and shopping centers were built. About 1984 the plateau’s population passed 10,000, and by 1985 its residents were starting to talk about incorporation or annexation. But it would be a few more years before anything really happened.

Failed Attempts

In 1991 local voters rejected a proposition to annex the southern half of the plateau to Issaquah (south of SE 8th Street, east to area ending roughly around 260th Avenue SE). That same year, Redmond included the northern half of the plateau (north of SE 8th Street, and west of -- again roughly -- 244th Avenue NE) in a long-range annexation plan. The Redmond plan was hotly contested and debated for more than a year before being abandoned.

In 1992 the question of whether to form a new city on the plateau was put to the ballot. Proponents argued that it would save tax dollars and create a community. Opponents argued that the lack of a business tax base and retail core from which to draw taxes in the proposed city made incorporation unrealistic, and that it would ultimately be more expensive, not cheaper, for local taxpayers. On September 15, 1992, plateau voters rejected Sammamish’s incorporation bid by a margin of 58.4 to 41.6 percent. Incorporation backers were surprised by the breadth of the defeat and blamed negative media coverage and concern over higher taxes for the resounding no from the voters.

The drive to incorporate languished for the next few years. Meanwhile, population and traffic gridlock on the plateau continued to grow. By 1997 incorporation was again a hot-button topic. This time, sentiments were more in favor. Many felt that the King County Council was more interested in urban than suburban issues, while at the same time, most local residents remained uninterested in annexing with Issaquah or Redmond. Explained plateau dentist John Rossi to a

Puget Sound Business Journal

reporter in 1997, “If we became part of Redmond, we would have to assume Redmond’s debt, and a lot of people here don’t ever go down into Redmond.”

SING and SHOUT

In 1997 area activists formed two groups to support incorporation: SHOUT (Sammamish Home Owners and Renters United Together) and SING (Sammamish Incorporation Neighborhoods Group). Once again, the debate to incorporate grew heated, with opponents again arguing that without an established business tax base, taxpayers would pay higher taxes for the new city’s services. But a rift also developed in the pro-incorporation forces. Representatives of SHOUT charged that SING had become too developer friendly; SING claimed that SHOUT was anti-development.

Despite the bickering, by the summer of 1998 the move toward incorporation was picking up speed. In June, King County released a feasibility study which concluded that a new city in the area would be self-supporting with a healthy annual tax surplus. This was the break incorporation supporters needed. A date for the vote was set, and differences were curbed. Explained incorporation activist Tom Harman, “We are trying to put a city together,” and presciently quipped, “Then the issue of personalities can make itself known” (Sammamish Review, October 1998, p. 7).

Incorporation

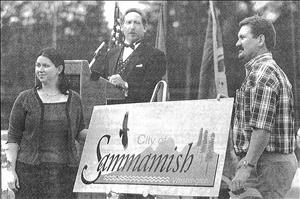

On November 3, 1998, local voters approved incorporation by a wide margin: 63.2 to 36.8 percent. A primary election for seven at-large city council positions was held in February 1999, and a general election was held on April 27. Sammamish officially incorporated at midnight on August 31, 1999, but the celebration was held three days before, on a happy Saturday afternoon and evening at Bill Reams East Sammamish Park. About 1,000 people turned out for the gala affair, called “Sammamish Day,” which came complete with a concert by 40 selected members of three symphony companies out of Seattle, an antique car show, and, of course, the incorporation ceremony. Sammamish Mayor Phil Dyer unveiled the city’s new flag, and Amy Sanders and Tom Burgess were announced the co-winners of the city’s logo design contest.

During the incorporation process there was considerable discussion over what to name the new city of about 28,000. Many favored Sammamish, which had originally been chosen during the failed 1992 drive to incorporate because state law required a name on the incorporation petition. Supporters liked the name because it had been used throughout the area’s history, but other names were suggested: Sahalee, Inglewood, Pine Lake, Heaven (a proposition quickly withdrawn), Timberline, and Monohon. An initiative or a public petition to rename the city could have been put on the ballot, but it wasn’t. Explained City Councilman Don Gerend in August 1999, “I think it’s more important for us to just get started at this point” (Sammamish Review, September 1, 1999, p. 7).

And there was a lot needing to get started. Sammamish’s city hall was in the Sammamish Highlands Shopping Center; there was no post office (and still isn’t); 228th Avenue looked much as it had 50 years earlier when the street was a bucolic country lane. But Sammamish took on the challenges and moved forward into the new millennium. Between 2001 and 2005, 228th Avenue was widened from two to four lanes between the Pine Lake and Sammamish Highlands shopping centers. In August 2006, Sammamish’s new city hall opened at the newly built Sammamish Commons. And on July 4, 2007, the city hosted its first “Fourth on the Plateau” celebration at Sammamish Commons, which seems to have the potential to become a big community event.

Meanwhile, rapid growth has continued in the nascent city, with Sammamish’s population passing 40,000 in 2007. The debate -- often passionate, occasionally rancorous -- continues over the future of how this growth can best be managed.

Sammamish is a Snoqualmie name. According to members of the Snoqualmie Tribe, the name is a corruption of two words: "Sqawx," the Snoqualmie name for Lake Sammamish, and "abs," a suffix which refers to people of a certain area.