On August 1, 1862, Victor Smith (1827-1865), Collector of Customs for the District of Puget Sound, sails into Port Townsend on the lighthouse tender USS

Shubrick

to move the Customs records to Port Angeles, designated as Washington Territory’s new Port of Entry. The citizens lock up the records, but Smith threatens to order the

Shubrick

to shell the Customs House and commercial district with her three 12-pound cannons. Reluctantly, the city council relents and Smith takes the records to Port Angeles. Over the next four years, the citizens of Port Townsend in Jefferson County will persist in their attempts to have Smith dismissed from office and will finally succeed. On March 7, 1865, Fred A. Wilson, a native of Port Townsend, is appointed Collector of Customs and immediately proposes that the Customs House be returned there. Washington Territorial Representative Arthur Denny introduces a bill in Congress to that effect, which passes on July 25, 1865. Port Townsend regains the status as the Port of Entry for Washington Territory, critical to the economy and subsequent growth of the city.

The Customs District

U.S. Congress established the Customs District of Puget Sound for Washington Territory on February 14, 1851. Simpson P. Moses was appointed the first Collector of Customs and chose Olympia as the official Port of Entry into Washington Territory. Since his headquarters were so far away, Moses found it difficult to monitor shipping activities in upper Puget Sound and recommended the Port of Entry be moved to Port Townsend.

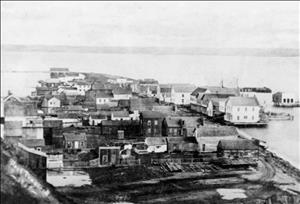

Colonel Isaac Neff Ebey (1818-1857), a Whidbey Island pioneer, succeeded Moses as Collector of Customs in 1853, at a salary of $1,200 per year and was successful in moving the Customs House to Port Townsend in 1854. Now inbound ships were required to stop at Port Townsend to clear customs and usually had to wait several hours for favorable winds and tides to continue their voyage. Ship captains often paid their crews there and most of the money was spent in town. Influential residents referred to Port Townsend as the “Key City” and believed it was destined to become the San Francisco of the Pacific Northwest.

Port Townsend's Victor Smith Problem

On July 30, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), at the suggestion of Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873), appointed Victor Smith, a newspaper editor from Cincinnati, Ohio, as Collector of Customs for the District of Puget Sound. Smith immediately disliked Port Townsend, creating feelings of hostility from the start. Smith thought the city was no more than a collection of shacks populated by uncouth Westerners. He immediately wrote to the Treasury Department, recommending the Port of Entry be transferred to Port Angeles. Also, Smith believed that the British intended to join forces with the Confederacy and could invade the United States from their naval base at Esquimault on Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

It wasn’t long before the citizens of Port Townsend learned that Smith was promoting the removal of the Customs House to Port Angeles, and that he and four other men had acquired title to a townsite there. Smith explained that the Port Angeles Townsite Company had been organized to develop land and build fortifications to discourage the British from invading the Union on behalf of the Confederacy. But Port Townsend’s citizens remained unconvinced.

When his letters to Secretary Chase failed to get results, Smith decided to make a trip to Washington D.C. to promote his plan to fortify Port Angeles and relocate the Customs House there. Since there was no Deputy Collector of Customs and he distrusted the local citizens, Smith asked the captain of the revenue cutter Joe Lane to appoint an officer to be the Acting Collector of Customs. The job was given to Lieutenant James H. Merryman. Loren B. Hastings, one of the city’s founders, was appointed as his deputy.

Smith’s lobbying effort in Washington D.C. succeeded. Secretary Chase sent a note to the Senate Commerce Committee stating that Port Angeles, although undeveloped, was a superior site because of its location nearer the ocean. On June 18, 1862, Congress authorized moving the Customs District of Puget Sound from Port Townsend to Port Angeles. In addition, President Lincoln signed an executive order on June 19, 1862, reserving Ediz Hook and the land within its protective arm for federal purposes, which included a lighthouse, a military reservation, and 3,000 acres as a townsite reserve. The lots would be sold with the revenue going into the treasury, helping to finance the Civil War (1860-1865).

Meanwhile in Port Townsend, Lieutenant Merryman and Loren Hastings audited the Customs House accounts and discovered they were $15,000 short. Lieutenant Merryman reported the discrepancy by letter to the Treasury Department. Because Smith had been revealed as a criminal, the citizens believed their Customs House was now safe.

Victor Smith's Use of Force

On August 1, 1862, Smith returned to Port Townsend on board the lighthouse tender USS Shubrick to resume his duties, but Lieutenant Merryman refused him access to the Customs House. Merryman said an audit of the receipts revealed that Smith was an embezzler and that he had reported it to the Treasury Department. Merryman said he would await official clearance before allowing Smith back into the office.

Humiliated, Smith left the customs office and returned to the Shubrick. An hour later, Lieutenant Wilson, captain of the Shubrick, came to the Customs House and informed Merryman that he had been ordered by Smith to load the ship’s three 12-pound cannons and train them on the Customs House. If the records were not surrendered within 15 minutes, he had been instructed to shell Water Street, the city’s commercial district. Merryman and Hastings conferred briefly with the city council and then, to save the city from attack, surrendered the keys to the Customs House. Wilson receipted for the files, loaded them on board the Shubrick, and sailed for Port Angeles.

A delegation of Port Townsend citizens traveled to Olympia to protest Smith’s unauthorized actions to Governor C. William Pickering. After talking to the delegation, U.S. Commissioner Harry Gill issued arrest warrants, charging Smith and Wilson with “assault with intent to kill.” When the Shubrick returned to Port Townsend, a U.S. Marshal boarded the vessel to serve the warrants, but Smith was not on board. The marshal attempted to serve Wilson, but he refused service, stating that he had no authority on board a government vessel. Confused, the marshal left the Shubrick to confer with the Commissioner Gill who told him to go back and arrest Wilson. As the marshal approached the Shubrick in his rowboat, Wilson ordered the two side-paddlewheels to be engaged, causing so much turbulence the rowboat could not approach and the ship left for Port Angeles.

In September 1862, Commissioner Gill convened a federal grand jury in Olympia. Forty men from Port Townsend were sent to Olympia on board the schooner Potter to testify against Smith. In the meantime, Smith arrived in Olympia on board the Shubrick, which anchored off Fort Nisqually. When the Potter sailed by the Shubrick, the cannon was fired in a derisive salute and a sign hung was over the stern renaming her “Revenue Ship Number Two.” The insult to Smith and the Shubrick would not go unchallenged.

The grand jury returned a 13-count indictment against Smith, charging embezzlement of public funds, procuring false vouchers, resisting arrest and assault upon the citizens of Port Townsend. The indictment was sent to Washington D.C. for review and a Treasury Agent was sent to investigate the charges. Secretary Chase cleared Smith of all charges and the indictment was quashed. Smith then filed a complaint against the Potter’s captain and the Port Townsend delegation for firing upon the Shubrick and illegally impersonating a government vessel. Secretary Chase, weary of the dispute, dismissed these charges too.

Things were quiet for several months. Smith busied himself in Port Angeles, constructing a house for his family and a large building, which he rented to the government for the Customs House. Meanwhile Port Townsend citizens built up a dossier for Washington D.C., denouncing Smith and the transfer of the Port of Entry to Port Angeles.

President Lincoln finally acquiesced and removed Smith as Collector of Customs, telling Secretary Chase that the degree of dissatisfaction with Smith was too great for him to be retained. With Lincoln’s permission, Chase appointed Victor Smith special agent of the Treasury Department, placing him in charge of all the customs districts on the Pacific Coast. L. C. Gunn, the Deputy Collector of Customs, officially replaced Smith on January 1, 1864.

Storm Takes Custom House

In the winter of 1863, a landslide in the Olympic Mountains created a huge reservoir above Port Angeles. On the night of December 16, 1863, the dam burst, sending a torrent of water through the town. Victor Smith was en route to Washington D.C., but his wife, Caroline, and four young children were at home. A logjam formed just above the Smith residence, which diverted the water and allowed Mrs. Smith to save herself and her family. Falling debris killed two Customs employees and the Customs House was swept off its foundation and carried out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The collapsed building was found by Makah Indians and towed ashore. They found the customs strongbox among the wreckage, broke it open and took everything of value. The records were thrown into the water, some of which were eventually recovered.

In February 1864, Smith’s brother, Henry, told authorities he had information that a strongbox belong to his brother and lost in the flood, was hidden in a nearby Klallam Indian village. Among other valuables, it allegedly contained $1,500 in bank notes and $7,500 in $20 gold coins. Eight Klallam Indians were arrested for the theft, but only one was convicted. The Indians claimed they had used the paper notes to start a fire and burned the strongbox. No trace of the gold coins was ever found.

On March 7, 1865, Fred A. Wilson was appointed Collector of Customs for the District of Puget Sound, replacing L. C. Gunn. Wilson was a native of Port Townsend and immediately proposed that the Customs House be returned there. Washington Territorial Representative Arthur Denny introduced a bill in Congress to that effect, which passed on July 25, 1865. Port Townsend had finally triumphed over her rival, Port Angeles, and regained the Customs House, critical to the economy and subsequent growth of the city.

In the summer of 1865, Treasury Agent Victor Smith was in San Francisco conducting official business. On July 28, 1865, he boarded the side-wheel passenger steamer SS Brother Jonathan, bound for Portland, Oregon. She carried 192 passengers and a crew of 50 officers and men. Among the passengers was the commander of the newly constituted Department of the Columbia, Brigadier General George Wright, his wife, and staff; and Paymaster E. W. Eddy with $300,000 in gold coins to pay the troops at Fort Vancouver. On July 30, 1865, the steamer struck the St. George Reef, north of Crescent City, California, in a gale, and sank in less than an hour, drowning 226 people, including Victor Smith. General Wright, his entourage, and the gold also went down with the ship. There were only 16 survivors who escaped in a lifeboat.

Key City Rejoices

There was great rejoicing when the Customs District of Puget Sound was returned to Port Townsend. The cannon on Union Dock was fired in salute as the Shubrick sailed into the bay, bringing the remains of the customs records. A public ceremony was held to honor Fred Wilson for his efforts in bringing the Port of Entry back to the city and people began clamoring for a new Customs House befitting the prosperous “Key City.”

In 1893, after many years of construction and several trips to Congress for additional funds, Port Townsend finally got a modern, spacious federal building that housed both the Customs House and the U.S. Post Office. This handsome stone and brick building, located at 1322 Washington Street overlooking Port Townsend’s Harbor, was dedicated on March 8, 1893. It was originally projected to cost $70,000, but wound up costing the public $240,000. The building, known as the Port Townsend Main U.S. Post Office, is listed on the Washington Heritage Register and National Register of Historical Places (listing No. JE00071). It is located within the Port Townsend Historical District, listed on the National Park Service’s Register of Historical Districts (listing No. 76001883).