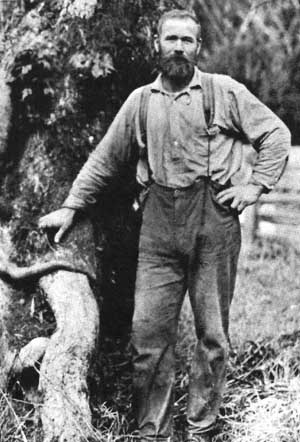

John Huelsdonk and his wife, Dora (Wolff) Huelsdonk, were the first settlers on the Hoh River and the Olympic Peninsula's most famous pioneers. Huelsdonk's homestead, claimed in 1891, was on the west side of the Olympic Mountains in Jefferson County, approximately 30 miles up the Hoh Valley. It is the wettest area in the continental United States, receiving more than 12 feet of rain a year.

John's Early Days

Bernard Wilhelm Johann (John) Huelsdonk was born on November 27, 1866, in Voerde in the little principality of Lippe on the lower Rhine River, which later became part of the German empire. In 1880, his parents, Herman and Elizabeth Huelsdonk, sold their estate in Germany and brought their family to America, settling on a large farm in Norwalk Township, Pottawattamie County, Iowa. According to the 1880 U. S. Census, Herman had five sons, Henry, John, William, Cornelius, and Herman, and one daughter, Hanna, living on the farm. Elizabeth Huelsdonk's father and mother, Cornelius and Sibyl Bernds, lived on the adjacent farm.

When John turned 21 in 1887, he left Iowa and came to Seattle. He found work with timber surveying parties near Snohomish and in east Clallam County, becoming a skilled woodsman. In 1888, he became a naturalized citizen, allowing him to file a claim for government land. When land was made available for homesteading in 1890, John and Cornelius Huelsdonk came to the Olympia Peninsula. After several excursions through the trackless forest, each brother decided to file a claim for 160 acres approximately 30 miles up the Hoh River valley. Together, they carved out pastures in the virgin forest and planted vegetable gardens and fruit trees.

The Hoh Valley

The Hoh Valley, approximately 17 miles south of Forks, is in Jefferson County on the west side of the Olympic Peninsula. More than 140 inches of rain per year made homesteading a challenge. Good land extended far up the Hoh Valley, but it was so distant from waterborne transportation and supplies that the latecomers often chose more difficult land closer to the mouth of the Hoh River. Those who picked natural clearings on flood plains often watched their fields and cabins wash away as water from rainstorms and spring snow-melt caused the river to flood and meander from one channel to another.

Many pioneers found that creating a homestead was exceptionally difficult in heavily timbered areas, and cedar swamps required draining as well as clearing. Creating farmland meant cutting trees and brush by day and burning the debris by night in order to have room to cut more the next day. The huge stumps remained as obstacles and blasting them from the ground was expensive, difficult, and dangerous. Burning involved drilling intersecting holes in the stump, and took time and patience.

Dora (Wolff) Huelsdonk

Dora Carolina Wilhelmina Wolff was born on October 2, 1863, in Schonemark in the Rhineland principality of Lippe. She was orphaned at age six. In Germany, the responsibility for raising and educating orphans fell to the landowners of the community, and she found a home with the Huelsdonk family. When they left Germany, Dora stayed behind, not wishing to be separated from her four brothers and one sister. She supported herself by cooking and housekeeping.

In 1886, Dora immigrated to America and eventually came to Iowa to visit the Huelsdonks on their farm. There she was reunited with John, her foster brother. But, in 1887, John left Iowa to seek his fortune in Washington Territory.

In 1892, John returned to Council Bluffs, Iowa, to visit his family. He told Dora about his beautiful homestead on the Olympic Peninsula and on October 5, 1892, they were married. Shortly thereafter, John and Dora Huelsdonk returned to the Hoh Valley to "prove up" their homestead. It was 17 years before Dora again saw civilization, during which time she bore four daughters: Lena (1893-1985), Dora (1895-1981), Elizabeth (1897-1989) and Marie (1902-1993). In 1909, Dora took her daughters to see the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle, one of the few times she ever left the Hoh Valley homestead.

The Hoh Valley in the 1890s

The Panic of 1893 caused Herman Huelsdonk to lose his store in Council Bluffs, for which he had traded his farm. Within the year, all the family still living in Iowa came to the Hoh Valley. Herman, his eldest son, Henry, and Cornelius Bernds filed claims on adjacent homesteads. After proving up their homesteads, requiring five years of improving and living on the land, all the Huelsdonks left the Hoh Valley except for John and his family, and Henry, who took over the family's property.

Many settlers left the Hoh Valley when President Grover Cleveland established the Olympic Forest Reserve in 1897, encompassing 2.2 million acres. It was the end to homesteading in the Hoh Valley and the dream of becoming a viable farming community that would one day bring civilization to their doors. Most of the settlers within the reserve's borders, tired of the isolation and heavy rainfall, abandoned their claims, convinced that without more people, roads, and civilization would never arrive. But the Huelsdonks stayed.

Working in the Woods

In order to make money during the early years of homesteading, John Huelsdonk worked as a logger at Port Crescent, a now-defunct logging town 17 miles west of Port Angeles. Unfortunately, while working in a camp north of Lake Crescent, his hands were pulled into a block by the sudden start of a donkey engine, and injured. The accident left him unable to perform any ordinary work at the logging camp, so he returned to farming and raising livestock. Over time, his hands healed and improved to the point that he could even milk cows. He earned money by carrying heavy backpacks and equipment for hunters, geologists, surveyors, and timber cruisers.

He also trapped fur-bearing animals and hunted predators (cougars, wolves, bears, and bobcats) for state bounties imposed to protect the elk and deer. During the year 1928, the U.S. Forest Service estimated that 500 deer and 305 elk were killed by predators and, depending on the species, a predator's hide was worth from $5 to $50 in bounty money from the State Game Department. It was during these years that John Hueldonk became a legendary woodsman.

Iron Man of the Hoh

People on the Olympic Peninsula began hearing stories about the "Iron Man of the Hoh." The stories about Huelsdonk's ability as a woodsman and his feats of strength were based in truth, but he neither sought publicity nor actively accepted it. In 1916, when trails were being cut into the wilderness of the Upper Hoh, he often strapped 175 to 200 pounds of provisions on his back and packed them up to trail crews. Because he was able to carry double loads, John received the salaries of two men, which was important to his family's economic welfare.

The story repeated most often concerned a camp stove, which, although bulky, was comparatively light. The stove was being carried to a trail camp and to make the trip worthwhile, Huelsdonk packed it with extra provisions including a 50-pound sack of flour. Altogether, the backpack weighed about 150 pounds. When a forest ranger whom he met on the trail commented on the size of the load, John explained the only thing bothering him was the sack of flour shifting around inside the stove, unsettling the load. Over the years, the story grew until the stove became a large kitchen range and the sack of flour became a barrel weighing 200 pounds. And there were many other stories, either true or partly true, told by the people of the Olympic Peninsula that made John Huelsdonk a legend in his own day.

Cougars and Bears

Huelsdonk was known as one of the greatest hunters and trappers on the Olympic Peninsula. By his own estimation, he killed more than 150 cougars and as many bears during his lifetime. In addition to packing heavy loads for money during the short working season, John supported his family by trapping fur-bearing animals and hunting predators for bounty. In September 1933, he was on fire patrol on the Snahapish Trail with his cougar dog, Tom, when a bear charged from the underbrush and hurled his dog 30 feet down the trail. The dog ran, but the bear, instead of giving chase, attacked Huelsdonk, knocking him down and grabbing him by the leg. Tom came back and attacked the bear so ferociously that it allowed Huelsdonk to escape and kill the bear with a shot from his rifle. Although suffering from claw wounds and a badly torn leg, he and Tom managed to walk five miles back to the farm.

District Fire Warden Charles Crippen came to the farmhouse to take Huelsdonk to the hospital at Forks, but he refused, saying that "he had lived in the wilderness 43 years without going to a hospital and he was not going to start now because of a few scratches" (The Seattle Times). It took Dora two days to persuade him see a doctor. He then walked 17 miles to the hospital at Forks. After bandaging his wounds and putting 32 stitches in his leg, the doctors managed to keep him in the hospital for three weeks. It was his only confinement until his death in a Port Angeles hospital.

In the fall of 1936, Huelsdonk was credited with killing the biggest cougar ever seen on the Olympic Peninsula. The cougar had been killing livestock on farms along the Hoh River during the 1930s and, because he left such huge tracks, he was named Big Foot. One afternoon, Huelsdonk was walking down a trail when he noticed a large number of crows feeding on the remains of a deer. Thinking the animal was probably killed by a cougar, he rushed back to the farm to get his cougar dogs and rifle, and began tracking the cat. An hour later, the dogs treed the biggest cougar Huelsdonk had ever seen. After being shot several times, Big Foot finally fell out of the tree at Huelsdonk's feet. The dead cougar measured 11 feet from his nose to the tip of his tail.

A World Without Roads

The Huelsdonk family lived in the Hoh Valley for more than 30 years before there was any road near their homestead. Farmhouses and outbuildings were built of hand-made lumber and shakes and furniture was built from any available materials. All supplies were either packed in on horses, by canoe, or on the backs of the settlers. In the late 1920s, Jefferson County finally completed Highway 101, which crossed the lower Hoh River, providing access to other communities by car.

But it wasn't until 1942, when lumber was needed for the war effort, that a bridge was built across the upper Hoh River within 100 yards of the Huelsdonk homestead and the road extended into the Snahapish Valley. The bridge was called the Huelsdonk Bridge and a campground was established nearby also bearing the family name.

On October 25, 1946, John Huelsdonk, age 79, died in a Port Angeles hospital, after being sick for two weeks with a heart ailment. After a funeral in Forks, he was taken back to the Hoh Valley and buried in the family cemetery on his father's homestead. Six months later, on April 27, 1947, Dora Huelsdonk, age 83, died of natural causes at their homestead and was buried next to John. Their graves were placed by a huge bolder that had been deposited on the spot during the last ice age, and marked with a brass plaque.

On February 11, 1972, the Huelsdonk Homestead, located eight miles west of the Hoh Ranger Station, Upper Hoh River, was listed on the Washington Heritage Register as an historic place (file No. JE00079), possessing particular value in commemorating American History.