Kittitas County, located at the center of Washington between the Cascade Mountains and the Columbia River, was part of the land ceded by the Yakama Tribe in 1855. Briefly part of Ferguson County (now defunct), then Yakima County, Kittitas County was established on November 24, 1883. Its geographic area is 2,297.2 square miles, placing it eighth in size among Washington counties. Ellensburg, home to Central Washington University and the Ellensburg Rodeo, is county seat. The Kittitas Valley became a stopping place for cowboys driving their herds north toward mining camps in Canada and northwest toward the Seattle/Tacoma market. By the late 1860s, cattle ranchers established land claims and cattle became the area’s foremost industry. The completion of a wagon road over Snoqualmie Pass in 1867, the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1887, the discovery of gold in Swauk Creek in 1873 and of coal near Cle Elum in 1883, and the 1932 completion of the Kittitas (irrigation) Project are important turning points in the county's history. Today the main industries are agriculture (including timothy hay to feed racehorses), manufacturing (food processing, lumber, and wood products), and government (including employment at Central Washington University).

A Land and its People

Kittitas County has a diverse ecology. The Wenatchee National Forest extends into its northwestern corner and in present-day times the U.S. Army’s Yakima Training Center extends into its southeastern corner. The Wenatchee Mountains (part of the Cascade Range) run along the county's northern border. The Saddle Mountains, Manastash, and Umtanum ridges form the east-west border between Kittitas and Yakima counties. The Cle Elum, Yakima, and Teanaway rivers snake through Kittitas County.

The first inhabitants of the Kittitas Valley were the Psch-wan-wap-pams (stony ground people), also known as the Kittitas band of the Yakama or Upper Yakama. Although the Kittitas were distinct from the Yakima (later renamed Yakama) Tribe, settlers and the federal government (for treaty purposes) grouped the Kittitas with the larger Yakama Tribe.

Interpretations of the meaning of the word Kittitas vary -- perhaps shale rock, white chalk, or white clay -- but in any case the name probably refers to the region’s soil composition. Another interpretation is that the bread made from the root kous was called kit-tit. Kous grew in the Kittitas Valley. “Tash” is generally accepted to mean “place of existence.”

The Kittitas Valley was one of the few places in Washington where both camas (sweet onion) and kous (a root used to make a bread) grew. These were staples that could be dried, made into cakes, and saved for winter consumption. Yakama, Cayous, Nez Perce, and other tribes gathered in the valley to harvest these foods, fish, hold council talks, settle disputes, socialize, trade goods, race horses, and play games.

The west side of the Columbia River at what would eventually become the eastern border of Kittitas County was home to some dozen Wanapum villages.

Fur trader Alexander Ross (ca. 1785-1858) was one of the earliest non-Indians to describe the Kittitas Valley. Along with his young clerk, two French Canadian trappers, and the trappers’ wives, Ross entered the Kittitas Valley in 1814 to trade for horses and stumbled upon an enormous tribal gathering. Ross described the scene in Fur Traders of the Far West:

“This mammoth camp could not have contained less than 3000 men, exclusive of women and children, and treble that number of horses. It was a grand and imposing sight in the wilderness, covering more than six miles in every direction. Councils, root gathering, hunting, horse-racing, foot-racing, gambling, singing, dancing, drumming, yelling, and a thousand other things which I cannot mention, were going on around us” (Ross, p. 23).

Ross calls this valley in which he encountered the encampment “the Eyakema Valley” but W. D. Lyman’s 1919 History of Yakima Valley and subsequent histories of the region identify the location as the Kittitas Valley.

The Catholic Missions

Beginning in 1847 Catholic Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate established missions in the lower Yakima Valley. In 1848 Oblate Father Charles Pandosy (1824-1891) founded the Immaculate Conception Mission on Manastash Creek near what would become Ellensburg. Pandosy served at the mission until 1849. After his departure, travelers used the Immaculate Conception Mission as an overnight shelter. Eventually the logs of which it was constructed were used as firewood. In 1853 the first emigrant wagon train passed through the Kittitas area en route to Naches Pass and Puget Sound. David Longmire, later a pioneer of Yakima, was a member of the party.

On March 2, 1853, Washington Territory was established. Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), newly appointed Territorial Governor, quickly set about establishing title to Indian-held land within the Territory.

On June 9, 1855, Yakima Chief Kamiakin (ca. 1800-1877) and other tribal leaders signed a treaty with Stevens ceding claim to all 16,920 square miles (10,828,800 acres) of the tribe's lands except a 1,875-square-mile (1,200,000 acre) portion of land to be used for a reservation. The future Kittitas County was part of the ceded land, along with the present Chelan, Yakima, Franklin, Adams, and large portions of Douglas and Klickitat counties, about one-fourth of the present state of Washington. Although the treaty was not scheduled to be ratified and go into effect until 1859, within one month of obtaining Kamiakin’s signature, Territorial Governor Stevens advertised in the Puget Sound Courier that the lands ceded were open to settlement.

Gold and the Indian War

Gold miners crossing the Kittitas and Yakima Valleys on their way to northeastern Washington combined with the threat of imminent white settlement angered the Indians. Kamiakin and other tribal leaders, having signed the treaty reluctantly, rejected it almost immediately. The Yakima Indian Wars of 1855-1856 and of 1858 followed. From May to September of 1856, Major Granville O. Haller directed a military encampment in the Kittitas Valley. It was not until after 1859 that many of the Yakimas were forced onto the reservation near Fort Simcoe. Congress ratified the Treaty of Yakima and President James Buchanan (1791-1868) signed the ratification proclamation on April 18, 1859. Cattlemen such as Ben Snipes (1835-1906) brought their herds to graze in the Kittitas Valley almost immediately, and within a few years non-Indian settlement in the area began in earnest.

Gold miners crossing the Kittitas region continued to be ubiquitous as they had been during the Indian Wars. In his memoir, Ka-mi-akin, early Kittitas Valley pioneer, cowboy, and eventually state senator A. J. Splawn (1845-1917) described how he and his brother William Splawn (1839-1921) bought horses from the Kittitas and Yakima Indians and sold them to gold-crazed miners. He recalled, “By 1864 this part of the country was gold-mad ... Spreading out like a fan, the gold hunters invaded every hole and corner of the mountains” (p. 213).

The Cattle of Kittitas Valley

The Valley was a cattleman’s paradise. Streams and bunchgrass were abundant so cattle could fatten and calf. It was a short cattle drive over Snoqualmie Pass to Seattle or a longer route over Colockum Pass to the Caribu Trail. A. J. Splawn described the Kittitas Valley in the summer of 1871 as a kind of Valhalla for cows and settlers alike:

“Thousands of cattle, driven in from the lower Yakima summer range, grazed the beautiful valley, whose fine bunch grass grew even up to the water’s edge. There were no flies of any kind to disturb the stock and there was cool, clear water in numerous small streams that wound through the grassy plain. The cattle became so fat that they had to hunt the shade early in the morning. It was a veritable cattle heaven. With no market for agricultural products, everybody was in the cattle business. The only labor attached consisted in putting up wild hay and fencing the ranches. Commercial crazes and get-rich-quick schemes had not yet reached this wild and beautiful land. The people were honest and happy. They sold their cattle once a year, and consequently paid their bills only once a year, but the trader knew he would get his money” (Ka-mi-akin, p. 303).

By the late 1890s, the beef cattle ranching industry was somewhat eclipsed by farming, especially growing hay and wheat. Better rail transportation to get herds to market stimulated a resurgence in the region’s cattle industry shortly thereafter. From the early 1870s to the 1960s many farmers also kept dairy cows and sold their milk to local creameries. Much of the resulting product was shipped to King County. The Kittitas Valley also produced a commercial wool crop. Sheep were initially raised in migrating bands, and shearing stations were scattered throughout the region. Kittitas also shipped lambs to eastern markets.

In 1867 Frederick Ludi (1832-1916) and John Goller (1813-?) (known as Dutch John) became the first non-Indian settlers to the Kittitas area, building a cabin on the site of what is now Ellensburg. In 1868, Charles (1831-1908) and Dulcina Thorp Splawn (1844-1869) and Tillman (1840-1918) and Louise Houser (1843-1916) became the first non-Indian families to make their homes in Kittitas. As other families came to the area they settled near necessities: timber and water. In 1870, A. J. Splawn and Ben Burch established the Robber’s Roost trading post in Ludi and Goller’s cabin. In 1871 Splawn sold the store to John Shoudy (1842-1901) and his wife Mary Ellen Shoudy (1846-1921). The Shoudys became the founders of Ellensburg.

On November 24, 1883, Territorial Governor William Augustus Newell (1817-1901) signed the act creating Kittitas County. The land had been part of Yakima County (established January 21, 1865). Residents of the Kittitas area had petitioned the Washington Territorial Legislative Assembly demanding that Yakima County either be divided into two counties or that, if the county were not divided, Ellensburg rather than Yakima City be named county seat. Much to the relief of the residents of the lower Yakima Valley, who wanted to keep their county seat, Kittitas County was split off from Yakima County and Ellensburg was named the new county’s county seat.

By 1886 whites were settling in and transforming the land. In January of that year, the Teanaway Bugle described Kittias Valley’s rapid development from a settler’s point of view: “Less than a year ago, Teanaway City was a howling wilderness while today we have a healthy village with a bright prospect for the future” (History of Kittitas County, Washington, 1989, p. 65).

Irrigating the Valley

For farmers in the Kittitas Valley, the key to this transformation from wilderness to village was irrigation. The farming potential of the rich Kittitas Valley bottomland was apparent to early settlers, who dug simple irrigation ditches. In 1885, the Ellensburg Water Company began surveying canal routes and building simple canals. By the early 1900s the Cascade Canal and Town Ditch on the east side of the Yakima River in Ellensburg and the West Side Ditch on the west side of the river were irrigating more than 26,000 acres in the lower part of the Kittitas Valley. This spurred the growth of the region’s commercial fruit industry.

In 1911 the Kittitas Reclamation District began preliminary surveys and cost analysis for what would become the High Line canal, the Kittitas Valley’s largest irrigation project. Lack of funding caused the project to lie dormant until 1925 when the federal Department of Interior's Bureau of Reclamation became involved in what was called the Kittitas Project. In 1926 construction on the canal (officially called the Kittitas Division of the Yakima Project) commenced. The canal was completed in 1932. The High Line Canal diverts water from the Yakima River just above the town of Easton and carries it out into irrigation canals completely encircling the Kittitas Valley, terminating where Turbine Ditch spills into the Yakima River. Reservoirs were created at Kachess in 1912, Keechelus in 1917, and Cle Elum in 1933.

Once the Kittitas Project was complete, the federal government solicited settlers to use the water and transform sagebrush into cash crops. Once full irrigation became available, existing farms were able to produce much more. Irrigated farmland was soon producing pea seed for commercial growers, sweet corn, potatoes, tree fruit, and hay. Wheat, however, continued to be largely dry-land farmed.

Hay from the Kittitas Valley fed Puget Sound workhorses. but by the 1920s the internal combustion engine made workhorses obsolete. In 1933 Washington legalized gambling on horse racing and the subsequent growth of the state’s horse breeding industry boosted the Kittitas hay business. Beginning in the 1950s Kittitas-grown timothy hay (high protein grass-hay) was exported to other states, to Japan as horse and dairy feed, and to Europe as feed for thoroughbred racehorses. Timothy hay is now the largest single cash crop in Kittitas County.

Towns of Kittitas County

Located at a traditional gathering spot for Indians and settlers alike, Ellensburg unsurprisingly blossomed into the major town in the Kittitas region. The Kittitas Localizer began publishing in Ellensburg on June 12, 1883, followed by the Kittitas Standard on June 16, 1883. The Ben Snipes and Company Bank opened in Ellensburg in September 1886, and the first Kittitas County Fair was held there in 1885. The arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1886 and the establishment of the Washington State Normal School (now Central Washington University), a teacher’s college, in 1891 brought further growth to Ellensburg. The University has been an anchor and major employer in the Ellensburg community.

Thorp, a quiet farming town nine miles northwest of Ellensburg, was home to a grist mill, two sawmills, and a creamery. Thorp served as an important community hub for farmers throughout the county.

The discovery of gold in Swauk Creek in 1873 prompted a gold rush, the creation of a mining district, and the growth of Liberty and Swauk. Placer-mined gold nuggets are the most common form of gold found in the region, but the Swauk Creek area is also one of the few locations in the world where crystalline gold wire has been found. This highly unusual formation is valued not for its weight but for its delicate wire-like sprigs of filigreed gold. It is so rare that most specimens are in museum collections.

Roslyn and Cle Elum prospered because of their large coal deposits. Coal mining in the Kittitas region was initially developed by the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1886 to fuel steam locomotives. The Northern Pacific owned the Roslyn town site and many area mines. The Roslyn-Cle Elum coalfield contained eight known seams, six of which were mineable. By the time in 1963 that the last mine in the region closed, Roslyn-Cle Elum had shipped more than 50 million tons of coal. From 1990 to 1995 Roslyn served as the setting for the television program Northern Exposure. Roslyn’s western storefronts, augmented by copious piles of Styrofoam prop snow, doubled for the fictional village of Cicely, Alaska.

Ronald, a smaller coal mining town northwest of Roslyn, suffered a devastating fire when a moonshiner’s still (at 250 gallons perhaps the largest in the state) exploded on August 17, 1928.

Easton, originally a sawmill town, was the last station for the Northern Pacific Railroad before it crossed the Cascades through Stampede Tunnel and the last stop for the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad before it crossed Snoqualmie Pass to Puget Sound.

Both Cle Elum and Ellensburg experienced devastating fires, Cle Elum on July 23, 1891, and again on June 25, 1918, and Ellensburg on July 4, 1889. Easton’s saloon district burned in November 1907 and the entire Easton business district burned in 1913.

The town of Kittitas was platted in 1908 and incorporated in 1931.

The town of Vantage, from 1914 to 1927 the site of a car ferry service across the Columbia river, was relocated in 1927 when the first Vantage Bridge was built and again in the early 1960s during the construction of Wanapum Dam. Vantage is the site of Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park. The park displays fossils of petrified wood uncovered at the site in 1927 and petroglyphs originally located on land subsequently inundated by Wanapum Dam. Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park is considered one of the most unusual fossil forests in the world and was designated a national natural landmark by the National Park Service in 1965.

The logging industry in the Kittitas area began in the late 1870s and was concentrated in the western end of the county. Lake Keechelus, Lake Kachess, and Lake Cle Elum all had logging camps. Sawmills soon followed. In addition to furnishing building supplies to the region’s growing towns, much of the early timber logged in Kittitas County was cut into railroad ties. In 1903 the Cascade Logging Company became the first large-scale commercial logging company to operate in the region.

Trails, Roads, and Rails

The main Indian routes into the Kittitas Valley were the Squaw Creek Trail (up Selah Canyon and over Selah Mountain, entering the Kittitas Valley at the head of Badger Pocket, then across the Valley) and the Snoqualmie Trail, used heavily by Indians traveling east-west across the mountains. Indians used a lower trail (later Snoqualmie Pass) for foot traffic and a higher trail (later Yakima Pass) for horse traffic.

Cowboys on horseback and herds of cattle could cross open range and ford streams, but wagonloads of goods required roads and bridges. As white settlement in the Kittitas Valley increased and cattle ranching gave way to agriculture, roads were constructed to link infant towns. These roads often followed Indian trail routes. A wagon road between Seattle and Ellensburg across Snoqualmie Pass was completed in 1867. Although this wagon route over the pass was unpaved and would remain so for half a century, it enabled goods from Seattle to reach the Kittitas Valley. Prior to 1867 all supplies to the Kittitas area came by wagon from The Dalles. This route was arduous enough to cause one stagecoach driver to conclude, “There is no hell in the hereafter; it lies between The Dalles and Ellensburg” (Dorpat/McCoy, p. 157). Once goods could be shipped by rail, the wagon route over Snoqualmie pass fell into disuse. The rise of the automobile in the early 1900s led to improvements on the old wagon road.

The main line of the Northern Pacific Railroad was completed through Kittitas County on July 1, 1887. The railroad allowed Kittitas Valley products to be efficiently shipped to customers beyond the county, immediately benefiting the cattle, dairy, produce, and hay industries.

The Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad reached Kittitas County in 1909 and on July 10, 1910, established daily local service. Several small logging railroads operated within the county from 1916 until the mid-1940s.

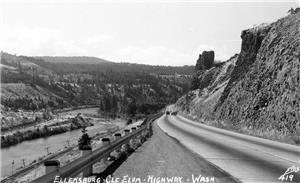

By the 1920s motor routes through Kittitas County were well established, if not always well paved. The Sunset Highway (Primary State Highway No. 2) crossed Snoqualmie Pass and went through Easton and Cle Elum before exiting Kittitas County over Blewett Pass. Beginning in 1930, Snoqualmie Pass was plowed during the winter to accommodate skiers. The Inland Empire Highway (Primary State Highway No. 3) carried traffic from Cle Elum through Ellensburg, exiting Kittitas County and turning sharply north as it proceeded toward Quincy in Grant County. Interstate 90 is now the main route from Snoqualmie Pass through Kittitas County, exiting the county at Vantage. Interstate 82 runs from Ellensburg south into Yakima County, and Interstate 97 runs from Virden over Swauk Pass toward Wenatchee.

Kittitas County today remains strongly agricultural. All available water has long been harnessed. Sagebrush-covered arid land (known as shrub-steppe) contrasts sharply with lushly irrigated crop acreage. The county’s gold mining and coal mining past are echoes of an earlier and wilder west, but the passage of time has not obscured the region’s pioneer heritage. Cowboy and cattle ranching culture and history continue to be celebrated on a grand scale at the yearly Ellensburg Rodeo.