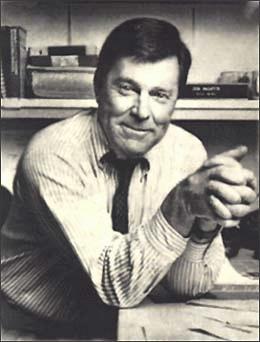

Donald E. “Don” McGaffin pursued a full, often-controversial 30-year-career as an investigative reporter and commentator, including 16 years in Seattle, where he was a major player in the golden years of television news, first at KOMO-TV and then at KING-TV. He accumulated a mantelpiece full of awards, including numerous Emmys. The injunction,

“Afflict the comfortable, and comfort the afflicted," an old mantra for fledgling journalists, was a compulsion for Don McGaffin. A muckraker in the classic sense, he exposed corruption and scandal in high places, and investigated and reported on a wide range of society’s ills. He was a stormy petrel described variously as gritty, tough, fearless, passionate, charming, impish, bizarre, and pugnacious -- literally and figuratively. He cheated death several times -- twice while serving in the U.S. Marines, three or four times as a reporter, and once or twice as a stroke victim. In 1985, at the apex of his career as media critic-commentator for KPIX-TV, San Francisco, McGaffin suffered a massive stroke. He survived and continued to write and even to speak. Don McGaffin died on May 29, 2005.

A High-Spirited Kid

Donald Edward McGaffin was born in Mount Vernon, New York, on July 23, 1926, to George and Elsie Finegan McGaffin, and grew up in nearby Elmsford, with a fascination for story-telling. Four children were born to the McGaffins: George, Don, Ethel Marie (“Mickie”), and Lorraine.

Don developed on “the small side of average” (Smith) but he was a “high-spirited kid” (Sheridan) and his father didn’t make growing up easy. George McGaffin managed the Westchester County bus system and was a school board member for a while. But he came from military roots, was a commander of the local American Legion post, and a practitioner of tough love. George taught young Don how to box, to defend himself, and those lessons in pugnacity became embedded deep in the boy’s psyche. He also developed into a promising baseball player, good enough to be scouted for a professional career, and the family always went to West Point games.

He joined the Marines at 17, in the middle of World War II and served as a radioman-gunner in the Pacific Theater. His father died in 1945 while Don was overseas. He re-enlisted when the Korean War began and served as a pilot, surviving two crashes; one in a New Guinea jungle, the other in the Sea of Japan.

Itinerant Newsie

After leaving the Marines, McGaffin attended Cornell University briefly, and graduated with a degree in political science-history from Davis & Elkins College, a small Presbyterian school in Elkins, West Virginia. He went on to earn a master's degree in journalism from Columbia University.

For the next 10 years, he was an itinerant newsie, drifting from the Schenectady (N.Y.) Gazette, to the San Diego Tribune, the Riverside Press-Enterprise, the Corona Daily Independent, and the San Jose Mercury-News.

Hard News

After the stint in Corona, where he dodged a bullet while covering a drug raid, he took time out to join a voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama, with civil-rights activists H. Rap Brown (b. 1943) and Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998), then leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Along with many others, McGaffin was picked up by sheriff’s deputies, roughed up and jailed.

While at the Mercury-News, in 1964-1965, he wrote a series of articles on the Minutemen and Citizens Councils of America, two prominent radical-right organizations flourishing at the time. The series earned him another beating.

Sparring on TV

Meanwhile, television news had been gaining viewers, with its mesmerizing images amplifying the visceral impact of events. By the mid-1960s, television was the major source of news for the majority of Americans and the medium was made for McGaffin.

He spent two years at KNTV, San Jose, and then in 1967 joined KPIX-TV, the CBS affiliate in San Francisco. He served as bureau chief in Sacramento, the state capitol, but the bureau was closed a year later. Westinghouse, the KPIX owner at the time, proposed moving McGaffin to KDKA-TV, its flagship station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. McGaffin declined and instead, in 1968, joined KOMO-TV in Seattle.

Given his track record, style, and radical mindset, it was an odd fit for the more low-key, establishmentarian station. “Don liked to fight,” said Jack Norman, McGaffin’s producer at KOMO-TV. “He enjoyed the sparring.” Norman was proud of their work, noting “Young, Black and Explosive,” an award-winning, prescient report on Seattle’s Central District powder keg; “The SDS: The Real Revolutionaries,” a report on the radical Students for a Democratic Society, and "Ramon.”

McGaffin's Pit-Bull World

In 1969, McGaffin and Norman, more or less in concert with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, exposed the Seattle police gambling tolerance policy and its attendant corruption. The exposé triggered the resignation of Seattle Police Chief Frank Ramon and the conviction of several police officers. Three years later, in 1971, fallout from the gambling probe would dethrone King County Prosecutor Charles O. Carroll, “arguably, the most powerful man in Seattle and King County” (Wilma).

A few years later, McGaffin would learn that one of Ramon’s successors, George Tielsch, kept a list of suspected subversive citizens, including then-Mayor Wes Uhlman, Uhlman's staff, and McGaffin. He read the list on the air.

In McGaffin’s pit-bull world, rank not only had no privileges, it provoked extra bite. Among his more notable confrontations at KOMO-TV was an interview on September 24, 1968, with Richard M. Nixon (1913-1994), then stumping the country for the presidency. Nixon, whose fear of the media bordered on paranoia, was expecting to awe a soft-hitting “local yokel” (Stiffler). Instead, he drew McGaffin.

In their book, An American Melodrama: The Presidential Campaign of 1968, authors Chester, Hodgson, and Page write: “It was not often that Nixon ran into a questioner like Don McGaffin ...” (p. 688). Responding to Nixon’s attacks on the record of his Democratic opponent, Hubert Humphrey (1911-1978), McGaffin asked Nixon about his own record of serving in an administration in which “the United States finds itself propping up military dictatorships.” Nixon was forced to admit the United States had done so, and the testy exchange so enraged the president-to-be that he kicked “every tire on his limousine before he got inside” (Diemond).

McGaffin In-Your-Face

If McGaffin was in-your-face on the air, he was no different out on the street. While covering a night of teenage rioting in Seattle’s University District on August 14, 1969, he was one of five reporters roughed up by police (Wilma).

In 1970, when the corporate reins at KOMO-TV began to chafe the easily chafable McGaffin, he had little trouble accepting an invitation from KING-TV, a few blocks away. KING-TV, anchor of the Bullitt communications conglomerate, had established a considerable progressive reputation, with editorials questioning the Vietnam War, tough documentaries, and investigative journalism. But its once-dominant position in the market had eroded and the new president, Ancil Payne (1921-2005), began making changes. In addition to McGaffin, Charley and Bob Royer, from Oregon City, Oregon, were hired. The newsroom became “a family of rough-and-tumble, intense and competitive people” (Tu), and the trio “did largely as they pleased” (Chasan, p. 192).

The Glory Days of Television

“The inmates were in charge of the asylum,” said Bob Royer, recalling a common assumption at the time. They also produced some of the most impressive, influential investigative reports on television and set a standard not only for the Seattle market, but for the country. They were major players in the glory days of television news in Seattle. McGaffin, given even freer rein, flourished, often to the consternation of management, his cohorts, and the subjects of his investigations.

“He helped people realize that television could be a pretty powerful player in journalism,” said Charley Royer (Tu).

“Don McGaffin was the incisive, biting voice of the liberal left on KING-TV before Seattle was liberal and leftist,” said Steve Excell, assistant secretary of state and longtime Republican stalwart. “He used to irritate the heck out of the Seattle Republicans, and he enjoyed every moment of it.”

McGaffin appeared to enjoy every moment of everything. He played as hard as he worked, always highly amped, always on, never shunning center stage. He could be histrionic, prickly, and not above vanity. Newspaper stories tended to list his age about five years on the short side. He was an excellent golfer and avid skier, always competitive, and a charmer with the ladies. For a time he drove an early Mini-Cooper with a British flag painted on the top.

Fast Mouth, Fast Mind

But he had “one of the fastest mouths and minds in TV news” (Paynter), and he produced an award-winning body of work that comforted the afflicted, and afflicted the comfortable.

In August 1971, while weekending with his wife, Ann, at their storefront apartment on Whidbey Island, he spotted several orcas captured and penned in Penn Cove. That led to “Catch 33,” a report on the abuse -- and deaths -- of killer whales captured for aquariums. The documentary changed the way the country viewed the mammals, and their pods are now Pacific Northwest icons.

The next year, his documentary on children’s flammable nightwear, “The Burned Child,” not only earned local and national awards, but led to reforms in the clothing industry, reforms shepherded by Senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989).

In 1975, “The Buck Stops Here,” produced with Charley Royer, helped end the political career of August Mardesich (1920-2016), a pro-business Democrat, Senate majority leader, and the most powerful member of the State Legislature.

Bob Royer was particularly proud of “A Political Chautauqua,” a series that examined the issues in the 1975 elections. Management apparently wasn’t all that impressed, so the Royers and McGaffin bought their own ads to promote the series.

Trouble in El Salvador

In 1981, KING-TV sent McGaffin and cameraman Randy Partin to El Salvador for three weeks, when U.S. involvement in Central America was still below the public's radar. They were in a mountain hamlet, “doing some footage on how the guerrillas were destroying villages in a kind of ‘scorched earth’ policy,” when members of the Farrabundo Marti Brigade captured them (Voorhees).

They were taken for CIA operatives (McGaffin was 55 at the time) and there was talk among the guerrillas of killing them, but they were released the next day. Out of the adventure came “Poor El Salvador,” another Emmy award winner.

Scoop Blows His Cool

McGaffin often made news as well as reporting it, both at play and at work, and if he could outrage Republicans, he didn’t ignore Democrats. On October 18, 1982, he was on a panel of newsmen interviewing Sen. Henry M. (Scoop) Jackson (1912-1983), at a civic luncheon sponsored by real estate executives at the Rainier Club. “Jackson blows his cool at McGaffin,” the Seattle Post-Intelligencer headline announced the next day.

Jackson, an avowed anti-Communist hawk, was no fan of McGaffin’s and KING-TV’s antiwar carping and he bristled when McGaffin questioned him about the proposed MX missile, a controversial first-strike weapon. “You don’t report the news. You just get on and you’re an advocate,” Jackson snapped, and a stunned McGaffin “declined to participate” in further questioning. Former Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman, the panel’s moderator, approached Jackson after the luncheon and said, “That’s the first time I’ve ever seen Don McGaffin speechless.”

Jackson responded, “That son of a b–– ” (Hadley).

Rising and Falling

By late 1983, television was changing, KING-TV was changing, McGaffin was changing, and the Royers had left to run Seattle, as mayor and deputy mayor. His work in Seattle had earned a mantle full of awards -- 13 local Emmys and a host of national honors.

After 13 years at KING-TV, by far his longest job tenure, McGaffin accepted an offer from KPIX-TV, San Francisco, and started the new year as its media critic and commentator. His quixotic goal: “To make television news accountable for itself” (McGaffin). He was 57, at the top of his craft, with a six-figure salary and an audience of a million.

It was a dream job and it lasted almost two years. On December 12, 1985, at 10:40 a.m., McGaffin arose from his desk, but then collapsed, victim of a massive stroke. He had been aware of the danger. Early stokes or heart attacks had killed his grandfather, father, and other relatives. Doctors feared he wouldn’t live, much less walk or speak again.

After two months, McGaffin was shipped back to Group Health Hospital in Seattle, his consciousness beginning to flicker back. At one point, it was too much -- not uncommon in such situations. “I decided it was time to die” and was “consumed with getting my gun,” a Colt .38 caliber Chief Special. His friends found it first and threw it into Lake Washington (McGaffin).

The Road Back

Finally, his considerable will took over and he began painful, frustrating, tearful months of rehabilitation -- with occupational therapists, speech therapists, and physical therapists -- relearning how to walk, talk, and read. “Imagine reading Sanskrit the first time” (McGaffin). But he did it, neuron by neuron, word by word, muscle by muscle, step by halting step. From bed to wheelchair to leg brace and cane. His right side was useless and he learned to write left-handed. He survived on savings and a $770 month disability payment. The bravado was still there, but the bitterness hovered just below the surface. “It makes you half a man” (Case).

On March 5, 1987, 15 months after doctors said McGaffin probably wouldn’t be alive, much less speak, he made the first of a dozen appearances on KCTS-TV’s “Nightsight” news program as a commentator and sometime-co-host. Barry Mitzman, “Nightsight” producer-host at the time, remembered McGaffin’s “singular style,” and “more audience response than anything I can recall. He struck a chord.”

Barry Mitzman remembered an interview with Richard Butler (1918-2004), the virulently racist neo-Nazi who viewed Jews as the children of Satan. “McGaffin says something like, ‘Well, we have a Jew right here,’ pointing at me. ‘What do you think of that?’ It was fun to work with him.”

McGaffin was happy to be on the air again and saw it as a gateway back to commercial television news, but when “Nightsight” was dropped from the KCTS schedule, so was he. He also worked briefly at KIRO-TV, writing and mentoring, at the behest of KIRO-TV anchor Aaron Brown, who had moved from KING-TV. Brown was one of many KING-TV news alumni who idolized McGaffin for his mentoring during their early days.

McGaffin also occupied himself writing a memoir and the occasional op-ed piece. One particularly scathing essay in The Seattle Times on October 1, 1988 -- reflecting his obsession with journalism’s culpabilities -- took Seattle’s media to task for ducking the Gary Little story.

The Gary Little Story

It was an ugly story. On August 18, 1988, King County Superior Court Judge Gary Little, 49, killed himself in the King County Courthouse with a .38-caliber revolver, after he was told the Post-Intelligencer was publishing a story the next day about his pedophilia -- his fondness for young boys. Little’s sexual predilections had been rumored for years, but he was a respected, socially and politically active judge, and the system looked away.

KING-TV reporters Jim Compton and John Wilson had obtained taped accounts from four adults who said they were molested by Little at Lakeside School, but the station killed the story (McGaffin, The Seattle Times). As did the Times. McGaffin named names, Seattle’s most prominent journalists, editors, and anchors, including KING-TV, and including himself.

Last Years

McGaffin persevered, his dream of returning as a television commentator undiminished, until a second stroke struck in 1999, hampering his speech. There was more rehab, this time with the encouragement of Dr. Rick Rapport, a Group Health neurosurgeon and McGaffin fan from the KING-TV days. Rapport, a founder of the Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, for several years hosted a conference on “Literature and the Art of Medicine,” at Seattle’s Asian Art Museum, and he cajoled a reluctant McGaffin to speak.

On May 28, 2003, McGaffin haltingly, sputteringly read from an essay, "The Stroke That Didn't Kill Me." Characteristically, he lambasted his audience, members of the medical profession.

McGaffin died on May 29, 2005, after a fall, related to another stroke, in his Magnolia home. He was 78 years old.

Said Shelby Scates, former political reporter for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, whose path occasionally crossed McGaffin’s: “He was very aggressive, especially for a television reporter, had a real good sense of where the story was. And he had a lot of fun doing it.”