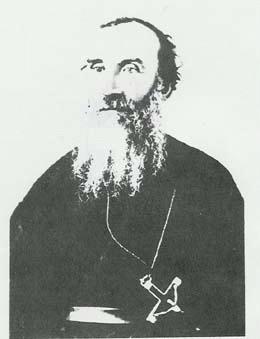

In July 1848, Father Charles M. Pandosy (1824-1891) establishes the Immaculate Conception Mission on Manastash Creek in the Kittitas Valley. Pandosy is a Catholic Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate. He operates the one-room mission until September 1849.

Making Do

Father Pandosy, along with fellow Oblate Missionary Eugene Casmire Chirouse (1821-1892), had only just been ordained a priest. Bishop Augustin Magloire Blanchet (1797-1887) ordained Chirouse and Pandosy at Fort Walla Walla on January 2, 1848. (Bishop Blanchet was the brother of Bishop F. N. Blanchet.)

Although an ordination was a solemn event, the vicissitudes of daily life in a Territorial stockade required improvisation. Father Ronald Young describes the scene in his Ph.D. dissertation on the Missionary Oblates:

“While attempting to maintain all the solemnity that the occasion required, but lacking some of the vestments, Brother Chirouse had to use one of Mr. McBean’s long nightshirt as an alb. [An alb is a long white robe worn by a priest at Mass.] As there had been no time to build any churches, they were ordained in the temporary residence of the Bishop. It was the same room that served as his chapel, refectory, recreation room, meeting hall, and dormitory” (p.75).

Chirouse and Pandosy were the first Catholic priests ordained in the future Washington Territory.

In December 1847 Yakama chief Owhi (d. 1858) visited Fort Walla Walla and asked that missionaries be sent to his people. In response Brother George Blanchet (1821-1906) and another missionary, Brother Celestine Verney, traveled to the Kittitas Valley. In early 1848 they started building a small structure on Manastash Creek to serve as a mission, but were unable to complete the work. On July 6, 1848, Blanchet, Verney, Chirouse, Pandosy, and two workmen returned to the site and resumed construction. The Immaculate Conception Mission, like the other Oblate missions in the Yakima Valley, were by necessity simple structures. Father Young describes them as “little more than wilderness huts, crude and uninviting ... a one-man hovel” (p.85).

Taking advantage of a clause in the Oregon Territorial Organic Act of 1848 that allowed missionaries with settlements among the Indians to claim up to 640 acres, on November 20, 1848, Father Pandosy filed a claim for the 640 acres surrounding Immaculate Conception Mission.

Difficulties and Hard Times

Although Pandosy’s mission had land, at least on paper, he was low on funds. Pandosy kept up a regular missionary circuit into the Yakima Valley and back to Immaculate Conception during the period between 1848 and 1849. On one trip he fell off of his horse and broke his shoulder. So great was his poverty during this time that he reportedly walked from Immaculate Conception to Fort Walla Walla barefoot.

Perhaps as a result of these pressures his mental health seems to have declined. On August 14, 1849, Father Chirouse stopped in at Immaculate Conception. Father Young’s dissertation recounts, “What he found shocked him. The bearded Pandosy was close to starving, his cassock was in tatters and he had been abandoned by all the natives. Although he had plenty of food, it became apparent that he was unable to take care of himself” (p. 93). Pandosy’s relations with the Indians had deteriorated to the point where one Walla Walla Indian threatened him with a knife during an argument. Chirouse nursed Pandosy back to health and in September 1849 took him to the Holy Cross Mission in the Yakima Valley.

Mission Structure and Mission

Thereafter, travelers seeking shelter used the Immaculate Conception Mission structure. Eventually it deteriorated to the point that the logs of which it was constructed were burned as firewood.

In 1855 Pandosy served as an interpreter for the Kittitas Indians during negotiations with the United States government, writing letters to officials on their behalf.

During the summer of 1856, Pandosy once again preached near Immaculate Conception, serving the spiritual needs of both Indians and the United States soldiers during the encampment of Major Granville Haller (1819-1897) in the Kittitas Valley.

In July 1879, Bishop Augustin Magloire Blanchet filed an affidavit in order to reclaim the land for Catholic use.