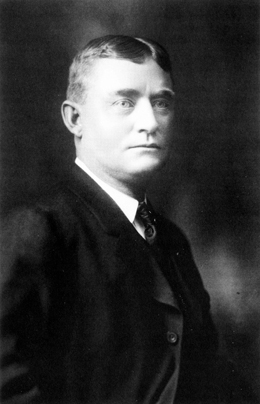

In late November, 1919, the first orphans arrive at the Hutton Settlement, Spokane’s new children’s home built and endowed by mining millionaire Levi W. Hutton (1860-1928). The opening of the home is the fulfillment of a dream of a man who himself was an orphan, raised by uncaring relatives. Hutton designed and will manage his orphanage along the most enlightened principles of the time, with a goal of providing a happy, healthy environment in which orphaned and needy children can grow up. Although not the first orphanage in Spokane, it quickly becomes the most prominent institution of its type in the region.

Levi Hutton was a locomotive engineer in the “Silver Valley” of the Idaho panhandle. In his off-duty hours, he, August Paulsen, and other shareholders toiled at a claim they had named the Hercules Mine. His wife, May Arkwright Hutton (1860-1915), kept the miners well fed during their backbreaking labor.

In 1901 they struck a large vein of silver and lead, and soon the newly rich Huttons moved to Spokane. Hutton expanded his business operations into Spokane real estate, May became a major force in the woman suffrage movement, and both gave time and money to philanthropy.

After May’s death in 1915, Levi Hutton began working toward the realization of his dream. He purchased 111 acres, enough land to function as a working farm, in the valley just east of Spokane. He then sent Spokane architect Harold C. Whitehouse (1884-1974) on a nationwide tour to research orphanage facilities. Hutton did not want his children’s home to have a grim institutional character, and together he and his architect decided on the cottage plan as the best of existing options. The facility Whitehouse designed consisted of an administration building and four “cottages” -- each in reality a gracious and functional Tudor-style home able to accommodate 20 children under care of a matron or house parents.

Hutton not only oversaw the planning of the physical facility, but also outlined the total administration of his orphanage and laid down the principles that would guide it over decades. The Deed of Trust and other founding documents specified that the home be non-sectarian; that siblings be admitted together; that the children be educated in the local public schools until graduation; that special consideration be given to orphans from the Coeur d’Alene mining district; and that the children do reasonable farm and house chores.

To carry out his wishes, Hutton named an all-woman board, many of whom were carry-overs from the Ladies’ Benevolent Society and its then still-existing Spokane Children’s Home. Most of these women were society matrons, the wives of Spokane leaders, yet they were a working board, furnishing the cottages, sewing for the children, and seeing to their educational, health, social, and recreational needs. Over the years, the board relinquished some of these tasks to paid staff as it assumed a more professional supervisory role in terms of personnel, admissions and business decisions.

Until his death in 1928, Hutton himself did much of the administration of his orphanage. The children loved and mourned “Daddy Hutton,” the closest to a father most had ever known. Hutton bequeathed to the Settlement his mining shares as well as his downtown Spokane commercial properties, including the beautiful Hutton Building. His handpicked assistant, young Charles S. Gonser, took over management of these assets as well as the administration of the Hutton Settlement, serving until his retirement in 1970. He was succeeded by Robert K. Revel, who retired in 1995, then by Michael Butler, the current administrator.

The Hutton Settlement has survived various challenges over the years -- threatened development and road encroachments on Settlement land, fluctuating revenues, complicated relations with the social work establishment and state regulations, difficulties in finding and keeping good residential staff, and the changing nature and needs of the children served. Because there are few full orphans today, the Hutton Settlement serves a different clientele -- children who for a variety of reasons cannot be raised by their own parents. Its beautiful buildings are now on the National Register of Historic Places. Through it all, the board and administrators have kept the Hutton Settlement true to the vision of its founder, and it continues to provide an important service to children of the region.