Daroga State Park, on the east bank of the Columbia River in North Central Washington, was once part of an orchard and ranch operated by legendary fruit grower Grady Auvil, who introduced Red Haven peaches, Granny Smith apples, Rainier cherries, and many other new fruits to the Northwest. Auvil moved to higher ground in the late 1950s when the Chelan County Public Utility District (PUD) began building Rocky Reach Dam. The reservoir behind the dam, called Lake Entiat, inundated part of the original orchard. The PUD bought the rest in 1981, developed it as a park, and leased it to the state. The park is an incongruous oasis of deeply watered lawns and full-service campsites, bisected by several huge, high-voltage transmission towers, painted bright orange and white. Kite flying is strictly prohibited because of the network of power lines overhead, humming with electricity from the dam that turned this section of the once-muscular Columbia into a well-mannered lake.

“Favorable Terms”

Daroga State Park lies in an area of the Columbia Plateau that had been occupied by Native Americans for thousands of years before the first white settlers arrived in the 1890s. The federal government recognized the ancestral rights of the Wenatchee, Chelan, Entiat, and Columbia tribes -- known collectively as the Middle Columbia Sinkiuse -- when it established the Columbia Reservation in 1879. The reservation’s original borders reached from the confluence of the Columbia and the Okanogan Rivers north to the Canadian border. The southern border was extended to the vicinity of the present-day park in 1880. With the expansion, the reservation encompassed nearly 3 million acres, set aside “for the permanent use and occupancy” of the Sinkiuse.

Whites began encroaching on mineral-rich areas of the reservation almost immediately. In 1883, the government “withdrew” a 15-mile strip in the Okanogan Highlands, opening it up to miners. The action sliced off nearly one third of the reservation. Reaction from the Sinkiuse was “much more hostile than friendly,” the Office of Indian Affairs reported. Even so, three years later, President Grover Cleveland ordered the rest of the reservation “restored to the public domain” (Executive Order of May 1, 1886).

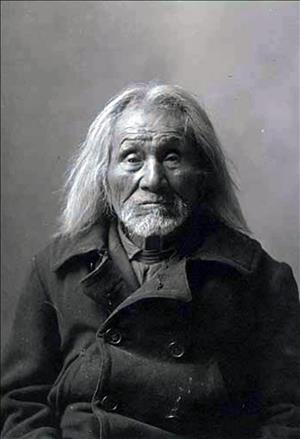

Under terms negotiated by Chief Moses (1829?-1899) and other leaders of the Sinkiuse, the government agreed to grant homesteads of up to 640 acres to individual Indian families who wished to continue living in the area. The government also agreed to provide livestock and farm equipment to help the Indians abandon their traditional lifestyles and become farmers. Moses and two other chiefs were to receive small pensions in return for their cooperation.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs estimated that fewer than 22,000 acres would be claimed as Indian “trust patent lands” -- less than 1 percent of what had once been the Columbia Reservation. The cost of meeting all the government’s obligations to the Sinkiuse was expected to be less than $85,000. “The terms upon which the Indians agree to relinquish their claims to this vast tract of country are regarded as favorable to the Government,” the commissioner concluded in a report to Congress (“Indian Lands in Washington Territory”).

From Scabland to Fruitland

Located on the edge of the parched scablands of the Columbia Plateau -- so-called because they resemble scabs on the backs of a dog -- the site of the future Daroga State Park attracted little interest from whites until after World War I.

This was due partly to questions over the ownership of lands that had been allocated to Indian families after the Sinkiuse relinquished the Columbia Reservation. In an effort to discourage land speculators, the allotments had been made inalienable -- meaning they couldn’t be sold -- for 25 years. Many parcels were sold anyway, often under fraudulent circumstances.

One such case involved 143 acres of land granted to Silico Saska, a Wenatchee who lived at the confluence of the Columbia and the Entiat River. Part of Saska’s claim was sold to the founders of the town of Entiat in 1896; the rest was sold to orchardists after his death in 1903. His heirs filed a lawsuit challenging the sales in 1912. The heirs prevailed in Chelan County Superior Court and in the Washington State Supreme Court. However, in 1917, Congress passed and President Woodrow Wilson signed a bill to cancel all restrictions on lands granted to individual Indians under trust patent laws. The act not only cleared the title to land in the town of Entiat, but to many other Indian lands across the West.

The other limitation on development along the middle Columbia was nature itself. Without supplemental water, the otherwise fertile land supported little more than bunchgrass. Early settlers discovered, more by accident than design, that the volcanic soil and temperate climate were particularly suitable for fruit trees. The first commercial orchard in Chelan County was established in the 1890s. The construction of the Highline Canal in 1902 brought a rudimentary irrigation system to Douglas County. But it wasn’t until the 1920s that the network of irrigation canals and ditches could support a large-scale fruit industry.

In 1928, Grady Auvil (1905-1998) and his two brothers, David and Robert, established an orchard four miles north of the small town of Entiat, along what the Sinkiuse had called “nch’i-wána,” meaning “Big River.” Auvil soon began experimenting with new varieties of fruit, using stock ordered from plant breeders around the country. One of his experiments produced the “Daroga peach.” The name, which lives on as the name of the park, was taken from letters in the first names of the three Auvil brothers: “DA” for David, “RO” for Robert, and “GA” for Grady.

Father of the Granny Smith

Auvil used his orchard as a testing ground for new fruits and new methods. In 1941, he established Red Haven peaches in the Northwest, just one year after the variety was developed by researchers at the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station in East Lansing, Michigan. Red Havens are now the most popular peaches grown in the United States. Later in the 1940s, Auvil experimented with the use of grass as a groundcover and mulch between rows of trees, an innovation that is now standard practice in the industry. In the 1950s, he planted rows of poplars as windbreaks in the orchard, another innovation that became common practice.

The original Auvil orchard remained in production for nearly 30 years until the construction of Rocky Reach Dam forced the family to move its operations to higher ground. Auvil continued to experiment in his new orchards. In the late 1960s, he planted a new white cherry called the Rainier, developed by researchers at Washington State University's Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser. Auvil wasn’t impressed initially with the cherry’s commercial possibilities. It bruised easily, and thus required special handling. But it produced a powerful pollen. When interplanted with Bings, it increased production of the valuable dark cherries.

Rainiers also had wonderful flavor. Auvil began snacking on the plump, juicy, rosy cherries as he worked around the trees. He brought them home to his wife and children, passed them out at Auvil Fruit Company board meetings, and gave samples to friends. In the early 1970s, he arranged for cushioned boxes of handpicked Rainiers to be sold at a special auction in New York. Buyers bought them up at twice the price of Bings. For a decade, Auvil Fruit Company dominated the growing market for fresh Rainiers. “We’re growing a yellow cherry up here that’s tremendously profitable,” Auvil told an agriculture trade journal in 1983. “I don’t know why more people don’t do it” (The Seattle Times, 2004).

Rainier cherries today are Washington’s celebrity fruit, coveted by consumers throughout the country and above all in Japan, where a single cherry sells for as much as 85 cents.

But it was with apples that Auvil really made a name for himself. He was the first commercial grower to plant Granny Smith apples in the United States. The tart, green apple had been developed in the late nineteenth century by orchardist Mary Smith in Australia and was popular in New Zealand but it was virtually unknown elsewhere. Auvil planted his first samples of the cultivar in 1972. He promoted it so successfully he became known as the “Father of the Granny Smith.”

In February 1998, Auvil received a Washington Medal of Merit -- the state’s highest honor -- in recognition of his leadership in the fruit industry. He died later that year, at age 93.

Dam Mitigation

Daroga State Park is one of 14 campgrounds and day-use areas owned by the Chelan County PUD. The parks were developed under recreation plans required by the federal government as compensation for land lost to reservoirs behind the district’s three hydroelectric projects: Lake Chelan Dam, built in 1903; Rock Island Dam, the first large dam on the Columbia, completed in 1933; and Rocky Reach Dam, completed in 1961.

The three most popular parks -- Daroga, Lincoln Rock, and Wenatchee Confluence -- are leased to the state. In 2002, the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission threatened to end the arrangement because of a budget crunch. The PUD increased its financial support of the parks, and the state agreed to continue operating them.

Daroga is a family-friendly park with one and a half miles of shoreline on the east bank of Lake Entiat. Two boat ramps and three docks provide easy access to the water. The park includes 17 campsites earmarked for boaters or hikers, on a strip of land commonly called “the island.” The main campground includes baseball and soccer fields, basketball courts, and almost clinically clean restrooms.

The park is a study in the transformations brought about by the damming of the Columbia. High-voltage transmission towers march through the campground like the figures in Navajo sand paintings, elbows locked and forearms pointing downward, carrying away electricity generated by Rocky Reach Dam. Children splash in a roped-off swimming area, disturbing the otherwise glassy tranquility of a river-turned-lake. The park’s lush lawns, watered daily by automatic sprinklers, provide stark contrast to the adjacent dun-colored desert.

Campers are warned that the sprinklers cover the entire 90-acre park, including concrete tent pads, and can run anytime between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. The prudent keep their equipment and supplies covered up.