On May 15, 1912, timber baron Michael Earles (d. 1919) opens an elaborate resort complex at Sol Duc Hot Springs in the Clallam County foothills of the Olympic Mountains. Earles credits Sol Duc's warm mineral waters with curing a serious illness he suffered. He has spent more than half a million dollars to construct a 165-room, four-star hotel, a three-story, 100 bed sanatorium, a large bathhouse, and gymnasium, golf links, tennis courts, croquet grounds, and more. For four years the resort attracts tens of thousands of visitors from across the country and as far away as Europe. Then in 1916 a disastrous fire levels virtually the entire complex. New facilities are built in subsequent years at Sol Duc Hot Springs, which since 1966 has been a concession of Olympic National Park, but none come close to matching Earles's short-lived vacation paradise.

The Sol Duc hot springs and their curative properties were well known to the Quileutes and other inhabitants of the Olympic Peninsula (as were the Olympic Hot Springs located a few miles east of Sol Duc on Boulder Creek, a tributary of the Elwha River -- both springs lie on the same inactive fault zone). According to tradition, Theodore Moritz, an early settler on the Quillayute River, became the first non-Indian to see the Sol Duc springs when a Quileute man he had aided showed them to him in gratitude. In the early 1880s, Moritz filed a homestead claim on the Sol Duc property, whose curative waters quickly began attracting visitors from Port Angeles -- a difficult two-day trip by wagon, lake scow, and trail -- and even farther afield.

Building the Resort

Visitors drank the mineral water and soaked in wooden tubs carved out of cedar logs. Eventually Moritz built a primitive bath house, wood-floored tents, and a dining room. Michael Earles, wealthy owner of the Puget Sound Mills and Timber Company, who had built mills at Crescent Bay and Bellingham and cut much of the timber between the Elwha and Twin rivers, sojourned at the springs in August 1903 with a dozen other prominent local citizens. Reportedly told by his doctor that he was dying, Earles believed that the mineral waters cured him. Hoping to make the cure more widely available, Earles obtained an option to buy the hot springs, which he did after Moritz died in 1909.

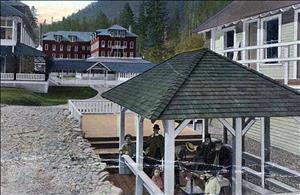

With Forest Service permission, Earles spent $75,000 building a road 14 miles from Lake Crescent to Sol Duc. When it was finished in 1910, he hauled in a sawmill that produced more than two million feet of lumber and 750,000 shingles to build the resort buildings. A brand new, 200- by 45-foot bathhouse with 30 tubs and a gymnasium replaced the prior bathhouse. There were also a ballroom, cabins, workers' quarters, an ice plant, and a steam laundry. Recreational facilities included golf, tennis, croquet, billiards, bowling, and theater. A three-story sanatorium presided over by Dr. William W. Earles featured beds for 100 patients and state of the art medical equipment, including an x-ray machine, laboratory, and operating room.

The centerpiece of the half-million-dollar resort was the four-star hotel. Each of the 165 guest rooms had view windows, electricity, steam heat, hot and cold running water, and telephones. The first story was constructed of massive upright fir logs and surrounded on three sides by a wide veranda. The large, ornate main lobby boasted brass chandeliers, massive pillars with gilt trim, and a huge fireplace.

Grand Opening

A well-publicized grand opening on May 15, 1912, heralded completion of the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort, described in the dedication pamphlet as a "Mecca for the sick, careworn, [the] pleasure-seeker and the sportsman" (Russell, 417). In an era when "taking the waters" was widely popular as both cure and vacation, Sol Duc became the leading resort spa on the Pacific Coast. Local residents took considerable pride in the elegant destination that brought visitors from across the nation and as far as Europe to Clallam County.

Though easier than the wagon journey and rugged trail of Moritz's day, it was not a short trip. The resort provided transportation from Seattle, beginning with a six-hour steamship trip to Port Angeles. From there guests were driven in large red Stanley Steamer automobiles to the east shore of Lake Crescent, which they crossed by steamboat. Another set of Stanley Steamers met them at Fairholm on the west end of the lake and drove them to the resort.

Given its remote location, the resort was largely self-supporting, generating steam and electric power and serving dairy products from its own herd and vegetables grown on the grounds. In addition to being used for tub, shower, mud, and vapor baths, the hot mineral waters were drunk by guests at the resort and bottled for sale elsewhere. Doctors prescribed the waters for a variety of ailments.

After the Fire

Earles's magnificent resort lasted barely four years. On May 26, 1916, sparks from a defective chimney flue ignited shingles on the hotel's roof. A strong wind spread the flames to the other buildings and within three hours all but the dance hall and health house were obliterated. During the fire, a short circuit caused the organ to play Beethoven's "Funeral March" repeatedly until it was consumed.

Insurance covered only a fraction of the loss and the magnificent buildings were never rebuilt. Michael Earles died in 1919 and Sol Duc passed through various hands over the next half-century. In the 1920s a more modest auto camp for middle-class vacationers operated on the site as did, reportedly, a bootlegging operation during Prohibition. Additional cabins and other buildings were constructed over the years, some of which also burned. Camping and RV facilities were also added.

The National Park Service purchased the Sol Duc resort in 1966 and incorporated it into Olympic National Park. The resort was completely rebuilt in the 1980s and its hot mineral baths continue to attract thousands of visitors, although the lavish elegance of Earles's spa is only a memory.