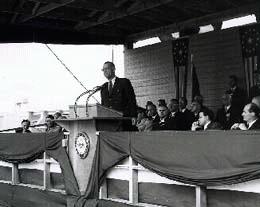

On May 9, 1962, Vice President Lyndon Johnson (1908-1973) dedicates Ice Harbor Dam on the Snake River. Planning and construction took 15 years due to lack of funding and to concerns about potential harm to migrating fish. Proponents of the dam countered environmental concerns with arguments that the electricity generated would support the Hanford nuclear weapons facility, and that the retained water would irrigate crops.

Snake River Potential

Ever since the 1860s gold rush in the Idaho panhandle, people have looked at the Snake River as the answer to numerous problems. Lewiston, Idaho, grew up at the confluence of the Clearwater and Snake rivers during the gold rush. Idaho promoters felt that the only thing keeping Lewiston from major growth was its distance from a major shipping center. But a solution was at its doorstep. If the Snake River could be tamed, people, crops, and manufactured goods could easily be shipped to and from Idaho. After the successful completion of Cascade Locks, steamship travel on the lower Columbia River was greatly improved. Other merchants and farmers joined Lewiston in its fight for river transportation.

The completion of various railroads temporarily interrupted the need for river navigation. Trains could ship goods much cheaper and soon put the steamers out of business. But by the 1930s, powerful tugboats could pull massive barges upstream and tow them downstream at a rate competitive with train travel. Idaho promoters once again began pushing lawmakers to create a navigable Snake River, namely by building dams. They were joined by the Inland Empire Waterways Association (IEWA), executive secretary Herbert G. West of Walla Walla. But they met stiff opposition from biologists, fish and game departments, and other interested parties who were concerned about the dams’ effects on migratory salmon and steelhead. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the eventual builder of the Snake River dams, also testified that the dams were not economically feasible based only on improved navigation.

Lower Snake River Dam Projects

It wasn’t until the end of World War II that Congress authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build four dams along the lower Snake River. Congress reluctantly agreed to spend the money only because of the hydroelectricity that would be generated. Cold War supremacy would require large amounts of electricity for defense projects around the Pacific Northwest.

The Portland District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers already had plenty of projects to work on, so the Corps created a new district to manage the work. The Walla Walla District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was formed in 1947, and district headquarters in Walla Walla opened on November 1, 1948.

Walla Walla District personnel assessed the preliminary design completed by the Portland District. The plan called for building the dam at Five Mile Rapids. The rapids were downstream from a small bay where riverboat captains tied up in the spring to allow icebergs to flow by. They called the bay “Ice Harbor,” thus providing the name for the new dam.

Ice Harbor Dam: Objections and Problems

The Corps couldn't begin work immediately due to the resistance of people concerned about the environmental effects of the project. Most of the objections concerned how many migrating fish would die as they attempted to clear the dam. These concerns and protests caused numerous delays in congressional funding for the dam.

In stepped Washington senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989) and Oregon Senator Herbert West. Magnuson and West believed cheaply produced hydroelectricity would encourage industrial development. Magnuson also argued that the dam was needed to power the Atomic Energy Commission’s Hanford Operations and other defense projects such as the manufacture of aluminum. Magnuson and West continued to press Congress for funding to start dam building.

In 1950, the Corps asked for $12 million to complete construction of Ice Harbor Dam. President Harry Truman supported the project, but Congress denied funding because of concerns over balancing the budget as well as the unknown effects of a dam on fish. The project was put on hold until January 1953, when President Truman asked Congress for $5 million to start the dam. It looked hopeful until Dwight D. Eisenhower assumed the presidency a few weeks later. He put a hold on all new dam projects.

The Dam Is Built

West and Magnuson continued to fight for the dams. They finally won $1 million to start the dam in 1955. The Corps used the initial appropriation to build an access road to the dam site. Additional money in 1956 financed the first cofferdam on the south shore, built to keep the construction site dry while building the fish ladders, powerhouses, and other structures on the Walla Walla County shore. Political dignitaries marked the placement of the first concrete on June 2, 1957.

In May 1959, the Corps erected a cofferdam on the north shore to complete the dam structures needed on the Franklin County side. The Corps made some design changes to the dam, particularly to the fish ladders, based on lessons learned from the Bonneville and McNary dams on the Columbia River.

Other expenses did not relate to the dam building itself. The Corps spent an additional $714,000 for 9,600 acres of adjacent land to the reservoir pool to relocate railroads and roads that would be flooded when the reservoir filled. The Corps also developed a number of parks along the banks of the Snake River: Hood, Charbonneau, and Fishhook parks in Walla Walla County, and Windust and Levy Landing in Franklin County. This work took place from 1957-1961. The dam generated its first power in December 1961.

On November 28, 1961, the Corps began filling the pool behind the dam, which was completed by April 1962. They named the 30-mile-long reservoir Lake Sacajawea, after the Shoshone woman who was a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition. The lake sits at 440 feet above sea level and contains a surface area of 9,200 acres. Several Indian burial grounds were inundated by the backwater. The Yakama, Warm Springs, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Colville tribes met with the Corps and all agreed to erect a single monument rather than relocate the graves. The Corps installed this memorial on a bluff overlooking the dam in April 1965.

The Dedication

Early in 1962, local officials organized the dam’s dedication. The Port of Pasco, Port of Walla Walla, Inland Empire Waterways Association, and others sent an invitation to the White House in the hope that President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) or someone from his staff would speak at the dedication. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson agreed to come. He arrived at the Pasco airport on the morning of May 9.

Johnson had just finished an engagement in Chicago and flew directly from there to Walla Walla. From there, he transferred to a four-engine Corvair plane and flew to Pasco, where he arrived 45 minutes later than planned. Idaho Senator Frank Church and Washington representative Julia Butler Hansen accompanied him.

Washington Governor Albert Rosellini (b. 1910) and Magnuson, who had flown in earlier, greeted Johnson as he came down the ramp and a crowd of some 1,200 others greeted him at the airport. Johnson, Church, and Hansen moved down a receiving line greeting representatives of the state, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Tri-Cities organizations. The Tri-City Drum and Bugle Corps provided music. Miss Tri-Cities, Judy Hutchinson, presented a silver platter to Johnson. Miss Indian America, Miss Brenda Bearchum, gave a presentation to the vice president.

During a short speech at the airport, Johnson gave credit for the success of the dam building project to the “quality of your representation in Congress.” He praised Magnuson, Representative Henry “Scoop” Jackson, and Julia Hansen. Following his address, a parade formed to downtown Pasco for lunch. There Johnson spoke about visiting the Hanford site to discuss progress on a new reactor.

Afterward, the entourage drove to the Walla Walla County side of the dam. Officials gave Johnson a tour and briefing, prior to the dedication. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Colonel James Beddow presided over the dedication ceremonies. Also on hand were Lt. General Walter K. Wilson Jr., M. G. Lapsley, and Lt. General J. L. Ryan, Commanding General, Sixth Army.

Governor Rosellini spoke on how the low cost of hydropower would allow construction of large projects in the state, including a light-metals industry, a chemical and oil-refinery industry, and a leading manufacturer of jet aircraft, space-age missiles, and space craft. He said it wouldn’t be long when more power would be needed.

At 3:00 p.m., Johnson gave his dedicatory speech from a podium near the river. He said the dam made the country stronger and our freedom more secure. He said President Kennedy set the tone when he said “Wise investment in a resource program today will return vast dividends tomorrow ...” He dedicated the dam, speaking of his "great pride in this accomplishment, and confidence in the future of this country." He recalled the day in 1955 when Magnuson fought for $1 million to be added to the public works appropriation to begin work on the dam, and lauded other western delegates for winning appropriation for the dam. Johnson then pushed the button that officially began dam operation.

After the dedication, two sky divers jumped over the dam. One jumper landed in the water, and the other broke his leg when the wind blew him into a pile of structural steel above the dam. Other activities included an Air Force flyover, a Marine parade, an Indian village, and refreshments. Johnson later flew to Seattle to dedicate the NASA pavilion at the World’s Fair.

Ice Harbor Dam

At completion, Ice Harbor Dam was 2,822 feet long and 130 feet above the river bed. The 10-bay spillway was 590 feet long. The dam contained 35 million pounds of reinforced steel. The navigation locks were 86 feet wide, 675 feet long, and 15-foot minimum depth, with a vertical-lift gate that weighed 700 tons (opened in October 1962). Dam builders excavated a million cubic yards of rock and dirt, drilled more than 90 miles of holes in bedrock to blast the foundation, and excavated more than 100 feet below the river bottom. Each of three generators produced 90,000 kilowatts for a total of 270,000.

At the time of completion, three bays were left empty for future expansion. Three additional generators and a powerhouse were installed in the 1970s, at a cost of $37 million. The three generators had a larger generating capacity of 111,000 kilowatts each. The new generators produced their first power early in January 1976. Shortly afterward, the Corps constructed viewing rooms for the fish ladders on both sides of the dam.

About 30,000 acres, mainly in Walla Walla County, were irrigated from water pumped from Lake Sacajawea behind Ice Harbor Dam. By 1975, all four dams were completed, and Lewiston finally had reliable river traffic, all the way to the Pacific Ocean.