Okanogan County, often called The Okanogan, is home to 38,400 people including members of the Colville Confederated Tribes on the Colville Indian Reservation. The area was one of the last in Washington settled by non-Indians because of its remoteness, but it was an early thoroughfare for prospectors en route to gold fields in British Columbia. In the twenty-first century, the county earns its living from agriculture and forestry with tourism offering additional opportunities. Grand Coulee Dam, the largest producer of electricity in the U.S., sits astride the Columbia River at the county's southern boundary.

The Okanogan Valley is a drained by a tributary of the Columbia River flowing out of British Columbia. The international boundary cuts across Lake Osooyos, which feeds the Okanogan River. The Canadian valley is spelled Okanagan. In the 77 miles between the lake and the Columbia River, the river drops just 125 feet, giving the route to the north an easy grade for travelers and vehicles, with plenty of fresh water and grass for stock. The Methow ("Met-how") Valley is another tributary of the Columbia flowing out of the Cascades. Okanogan County is 5,281 square miles in size with as much as 70 percent owned by the state and federal governments. The west half of the Colville Indian Reservation occupies the southeast corner.

The Okanogans

For hundreds of years prior to contact with Europeans, the indigenous peoples of The Okanogan consisted of three major bands of a group called the Northern Okanogans or Sinkaietk, the Tokoratums, the Kartars, and the Konkonelps. They spoke as many as seven dialects of the Interior Salishan or Interior Salish language related to the languages of Puget Sound tribes, but very different from the other languages of the Columbia basin.

The Okanogans led a semi-nomadic existence, starting in permanent camps through the winter, then leaving to hunt bears in the spring, catch salmon in the summer, and hunt deer in the autumn. One of the most prolific fisheries was at Kettle Falls where the Columbia dropped as much as 20 feet. Women gathered any of 100 varieties of nuts, roots, and berries. Permanent camps consisted of teepee-like longhouses covered with hides, bark, and particularly tules, which grew along water courses. Each house was 12 to 15 feet wide and as long as 150 feet, housing a dozen or more people. Summer huts were covered with transportable mats woven from tules.

The Okanogans traded with other tribes to the south and across the Cascades to the west. In the late 1700s, the Okanogans acquired horses from other tribes both for transportation and for food. In 1782-1783, a smallpox epidemic may have cost the lives of a third to a half of the people in the Okanogan.

Contact

William Clark of the (Lewis and Clark expedition) Corps of Discovery was the first to map the Okanogan River based on his interviews of Indians at the mouth of the Snake River in 1805. David Thomson of the North West Company was the first European to visit the Okanogan River when his expedition paddled past the mouth down the Columbia in July 1811. A few months later, David Stuart and Alexander Ross of the American Pacific Fur Co. built a log cabin at the mouth and called it Fort Okanogan. This became a base for trading goods for beaver pelts collected from the north by Indians. Fort Okanogan was taken over by the North West Co. in 1814, which sold it to the Hudson's Bay Company in 1821. The paths up the river became the Okanogan Trail.

Territorial Governor Issac Stevens (1818-1862) signed the Walla Walla Treaty with tribes of the Columbia Basin in May 1855. He regarded the Yakima Chief Kamiakin as representing the Okanogan bands to the north, even though Kamiakin did not even speak their language. Stevens met, but never signed treaties, with the northern tribes before war between Indians and newly arriving settlers broke out. The Indian War of 1855-1856 did not really touch the tribes of The Okanogan.

Gold strikes in New Caledonia -- the Okanagan (Canadian spelling) and Fraser River valleys of British Columbia -- in 1858 attracted prospectors from California to the region by way of the Columbia River. These incursions triggered Okanogan County's one battle of the Indian wars, an ambush of a 160-member party of miners at a defile called McLoughlin Canyon (named for the leader of the party) on July 29, 1858. Three miners died and several more were wounded. The U.S. Army launched a punitive expedition into the valley, but they turned back without finding anyone to punish. The following spring, the Army established Fort Colville at Mill Creek in the Colville Valley.

The boundary between the U.S. and Canada ran through Lake Osoyoos and was marked only with a Canadian customs station at what would become the town of Osoyoos. As miners discovered gold and silver, a precise boundary was needed to clarify claims. From 1858 to 1861, surveyors from the Royal Engineers and the U.S. Army established a boundary starting at Point Roberts and running to Montana. The location of the border was determined sometimes through scientific calculation and sometimes through consensus and compromise. The engineers cut a 60-foot swath through timber and erected stone markers to mark their survey. Since most of the traffic was northbound in the early years, the U.S. did not establish a Customs Port of Entry until 1880.

Pioneers

The honor of being the first American to settle Okanogan County falls to one of two men, Hiram Francis "Okanogan" Smith (1829-1893) or John Utz (b. 1824). Utz was a "shadowy backwoodsman" (Wilson, 67) and moved on, but Smith stayed to became a prominent commercial and political leader, so Smith is often identified as the county's First Citizen. In the 1850s and 1860s, few pioneers made their homes in The Okanogan, but many miners arrived to dig gold and silver. With the departure of the Hudson's Bay Company, former employees took up farming in the Colville Valley.

The Okanogan tribe and other tribes of north central Washington Territory never signed treaties ceding their lands to the U.S. Government. In 1871, Congress authorized the president to establish reservations by executive order and Ulysses Grant created the Colville Indian Reservation in 1872. This was to be home to about 4,200 Methows, Okanogans, San Poils, Nespelems, Lakes, Colvilles, Calispels, Spokanes, and Coeur d'Alenes. Non-Indian settlers whose homes fell within the vast area protested and had the Colville Valley in the east subtracted. At one time, all of today's Okanogan County was an Indian Reservation. But miners and settlers lobbied the government relentlessly until the reservation was reduced in 1886 to the contemporary Colville Indian Reservation, home to the Colville Confederated Tribes.

Gold! Silver!

Once Indian title to most of the Okanogan had been extinguished in 1886, miners were free to exploit the gold and silver there. The ensuing mining boom saw the founding of Ruby City (later Ruby), Conconully, Solver, Loop Loop, Oro (later Oroville), and other camps, and the construction of some substantial mines and stamping mills. Chesaw comes from the Chinese chee-saw or good farmer and a cordial host and is the only municipality in the U.S. named after a Chinese. In 1890, the non-Indian population of the county numbered 1,509.

The end of the boom came with the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, the drop in the price of silver, and the Panic of 1893. Mining continued to be an important activity into the twentieth century, but Okanogan County was never more than fourth in gold production in the state.

Home Rule

American settlers in the Willamette Valley had included The Okanogan in the Vancouver District of Oregon in 1844, then in Clark County in 1845. In 1854, the Washington Territorial Legislature placed the Okanogan Valley in Walla Walla County, and in 1860 made it part of Spokane County. The legislature created Stevens County in 1863, encompassing Okanogan and Ferry counties. In 1864 Spokane County was folded into Stevens, which then covered most of northern Washington east of the Cascades before various other counties (including a revived Spokane) were carved from it, as Okanogan eventually was.

Colville was the county seat of Stevens County. Anyone in the Okanogan Valley needing to register or change a title to land had to travel days to the courthouse

. Okanogan ranchers Cullen Bryant Bash, Henry Wellington, and school teacher and miner David Gubser organized a petition drive for a separate county. Bash delivered it to the Territorial Legislature and worked hard to get it passed. On February 2, 1888, Okanogan County came into being. In 1899, the state legislature took the southern portion of Okanogan (and northern Kittitas) to form Chelan County, establishing Okanogan County's final boundaries.

Ruby was the first county seat, but voters moved the seat to Conconully after eight months. In 1914, after periodic attempts at a new county seat, voters decided that Okanogan would be home to the courthouse.

Settlement

Since most of the county was Indian land through the 1880s, formal surveys did not begin until 1893 and would take 12 years to complete. Impatient settlers squatted on unsurveyed Indian land. They defied officials who might evict them when their claims conflicted with legal homesteads, so most of the squatters rights came to be recognized as valid. The population almost tripled from 1890 to 1900 and almost tripled again by 1910 as homesteaders moved in, not so much by prairie schooner, but by train. In 1913, migrants made the trip from St. Paul to Spokane in two-and-a-half days. Fifty years before, the journey had taken six months or more. Once the new arrivals took up their claims, they could take title by residing there for five years and improving it and by paying a $15 fee.

Water

Although grass and field crops naturally flourished with the 12 to 13 inches of annual rainfall, orchards required additional water. Pioneer Hiram Smith irrigated an orchard near Lake Osoyoos in the 1860s. In the 1880s, squatters in the Okanogan and Methow valleys dug ditches individually and as associations. In 1908, Congress passed the Reclamation Act (Newlands Act), which got the Federal Government into the ditch business. At first, the bureaucrats deemed The Okanogan too small for their trouble, but finally approved $500,000 for the first Bureau of Reclamation project in Washington.

Between 1907 and 1910, engineers built an earthen dam, which formed Conconully Lake, and the first water irrigated 2,000 acres that orchardists had painstakingly planted with apple saplings. Until the water flowed, they had carried buckets of water to keep each young tree alive. Seven years later, the first apples shipped from the project. In 1919, this became the Okanogan Irrigation District. The soil proved to be much more absorbent than planned and the project never achieved the dream of 10,000 acres of orchards.

This and other farmer-owned projects often required landowners to sell off most of their original homesteads since, by law, no more than 40 acres per plot could receive water. New arrivals moved in to snap up the smaller, potentially more profitable parcels. It took years for the projects to overcome problems with seepage, washouts, and evaporation, but irrigation transformed The Okanogan.

The federal Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 sought to integrate Indians into American society by giving each tribal member 160 acres of land to farm, and turning the rest of reservation lands over to non-Indian settlement. In 1898, the remaining 1.3 million acres of the now diminished Colville Reservation was opened to mineral exploitation. In 1905, a majority of the adult Indians were convinced to relinquish rights to the South Half in order to be paid for the North Half taken from them in the 1880s. Each Indian received $500. In 1916, about a third of the South Half was opened for settlement and a new land rush.

In 1907, forest reserves owned by the federal government became national forests and the following year, Chelan National Forest was established. In 1911, Okanogan National Forest was split off from the Chelan unit and still holds the majority of land in the county both east and west of the Okanogan Valley.

Transportation

The Okanogan and Columbia rivers were both barriers and thoroughfares depending on the direction of travel and the time of year. Indian canoes ferried people, goods, and animals across the streams, but travel up and down the valleys was mostly by land. Beginning in July 1888, the Pasco-built stern-wheeler City of Ellensburgh, offered service up the Columbia and just up the Okanogan as far as Monse. The Columbia rapids and seasonal drops in the river prevented reliable year-round travel. If rapids were too swift, the crew ran a line to the shore and winched the vessel past the fast water. In the spring, steamboats might reach as far up the Okanogan as McLoughlin Falls. Freight and stage lines connected The Okanogan with points downstream toward Wenatchee and upstream toward Spokane.

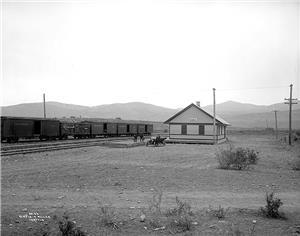

Rail service to Okanogan County resulted from James J. Hill's desire to link the transcontinental Great Northern at Spokane Falls to Nelson, B.C., and came to the county not from the south, but from Canada. Between 1902 and 1906, Hill built the Washington & Great Northern, which meandered north and west across the international boundary. In Canada the line was called the Vancouver, Victoria & Eastern.

Trains first reached Molson in the Okanogan Highlands from Spokane on November 2, 1906. County residents clamored for more direct service and finally the Great Northern laid tracks from Oroville south to Pateros by 1913 and to Wenatchee the following year. Twice-daily rail service to Oroville put the steamboats out of business and marked the end of Okanogan County's frontier days. With a rail connection, loggers moved into the county and began to exploit timber resources.

The Great Depression (1929-1939) did not devastate Okanogan County as it did other rural areas in the U.S. Residents already lived fairly simple lives with a high degree of self-sufficiency. Relief programs helped farmers and merchants, and hundreds of men in the Civilian Conservation Corps built roads, trails, campgrounds, fire lookouts, the Salmon Meadows Ski Lodge, and fought fires. The timber industry struggled with falling prices, but since the county did not produce dimensioned lumber for the construction market, demand continued. When the Government raised the price it paid for gold to $35 an ounce, miners returned to the hills either as employees of rejuvenated operations or as independent prospectors.

The big spur to the economy of the county and the state was the construction of Grand Coulee Dam in the south near Coulee City. This part of the county had been bypassed by settlement and quickly became home to 15,000 people. By 1937, unemployment in the county was at 6 percent. Irrigation supplied by the dam enabled the cultivation of a half million acres of arid land.

Modern Times

Cattle ranching led to The Okanogan's most notable celebration and athletic event, the Omak Stampede. This annual rodeo was first held in August 1934. Publicity Chairman Claire F. Pentz proposed a horse race involving a wild plunge down a sandy bluff and across the Okanogan River to the arena. Most riders were Native Americans and the winner received a cash prize, a saddle, and a belt buckle. Winning was a significant accomplishment for residents of the Colville Reservation.

The 55-second, one-fourth-mile Suicide Race became the most popular -- and most controversial -- of the county's annual events. Some horses were injured and a few had to be destroyed. When two 13-year-old riders were hurt, the minimum age was set at 16. Horses had to be five years old. Animal protection advocates persuaded some sponsors to withdraw in the mid-1980s and pressured organizers to stop the event.

In 1999, the race was cancelled when Indian participants boycotted the race over a dispute about parking for their encampment and when the river was too high. The Indians returned the following year along with the protests over cruelty to the horses, but the races still ran.

The late twentieth century saw residents struggle with economic development that would impact its rural way of life. (The county's first stoplight was installed in the early 1980s and the second, for a WalMart, in the mid 1990s.) The construction of State Route 20 (North Cascades Highway) from the Skagit Valley across Okanogan County to the Methow Valley in 1972 ended some of the remoteness of the Methow, at least during the summer months.

In 1968, developers announced plans for a ski resort on Sandy Butte near Mazama in the Methow Valley. In 1978, Methow Recreation, Inc. made formal application for the 3,600-acre Early Winters resort. The project hoped to place Washington ahead of skiing destinations like Colorado and Utah and would produce 1,200 jobs, which might compensate for the decline of the logging industry. But Early Winters would attract an average of 3,500 skiers a day and drastically change the character of quiet, rural area, turning it into something like Vail, Colorado. The Methow Valley Citizens Council organized to block the project and the controversy divided the small community. The matter went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which cleared the way for the project in May 1989.

That same year, Crown Resources, a Denver mining company, discovered gold underneath Buckhorn Mountain near Chesaw and announced plans for the Crown Jewel Mine, an open-pit operation that hoped to extract 1.4 million ounces of gold over eight years. Crown proposed to build Washington's largest open-pit mine, which would generate some 97 million tons of waste and leave a lake in the pit. A process using cyanide would leach the gold out of the ore. Up to 75 high-wage jobs would be created in an area with chronically high unemployment.

The Early Winters project generally prevailed against its opponents in court, but in 1992, financing fell apart and the 1,200 acres of property were auctioned off to pay debts. The concept reemerged in 1996 as a smaller resort called Arrowleaf, with cross-country skiing instead of downhill skiing, and with some community approval. Developers hoped to expand Arrowleaf, but in December 2000 after spending $20 million and years waiting for regulatory approval, they dropped the plan.

A month later in January 2001, The Trust for Public Land purchased 1,020 acres once envisioned for Early Winters and preserved it from development.

Environmental groups opposed the Crown Jewel mine for 10 years. In 1999, U.S. Senator Slade Gorton sought to overturn a Clinton Administration ruling against the project by tacking an amendment onto funding for a military action in Kosovo. The key defeat for the open pit plan was a withdrawal of a State water permit in 2000 because of concerns about the pollution mitigation measures. By that time the price of gold had dropped and the new operators decided to dig an underground mine and to process the ore at an existing facility in Republic, Ferry County.