On October 23, 1875, Dr. Dorsey Syng Baker (1823-1888) completes the Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad from Wallula, on the Columbia River, to Walla Walla. Work on the railroad began in 1871, and it is completed four years later. Dr. Baker celebrates by offering a free round-trip ride on the new railroad. Hundreds come from around the valley to see the new train. Walla Walla residents board the train, ride to Wallula, and enjoy a picnic before returning by train to Walla Walla. The line will become part of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Transporting Wheat

As early as 1862, the townspeople thought of building a railroad from Walla Walla to Wallula. Farmers raised wheat and other staples that were in demand in Idaho gold camps. But when the Idaho gold rush went bust, Walla Walla County farmers had to find a new market for their agricultural products. They needed a means of transportation. It was impractical and expensive to transport crops by wagon to the port at Wallula. They needed a railroad.

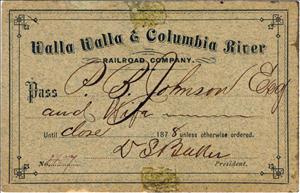

In 1868, Dr. Dorsey Syng Baker, A. H. Reynolds, I. T. Reese, A. Kyger, J. H. Lasater, J. D. Mix, B. Scheideman, and W. H. Newell incorporated the Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad Company. The men hoped to finance the railroad by the sale of public bonds. Though the townspeople needed the railroad, they were unwilling to pay for it. After several attempts to finance the railroad in this manner, the original corporation folded. However, Dr. Baker wasn’t willing to quit. He decided to finance the project with his own capital. Others who joined him in the venture included W. Stephens, I. T. Reese, L. McMorris, H. M. Chase, H. P. Isaacs, B. L. Sharpstein, O. Hull, and J. F. Boyer.

In 1871, he hired General James Tilton to survey the 32-mile route. Tilton estimated the cost of the roadbed would be $166,988, the rail $358,784 (if using standard 45 pound English rail), and two locomotives, rolling stock, and other equipment, about $673,367. Baker figured he could get the work done for much less. The biggest savings came by using narrow gauge locomotives rather than the more expensive standard gauge. He would also build his rolling stock locally rather than buying ready-built cars. He achieved big savings by using wooden rails on which he fastened strap iron. The story that he used rawhide on the track and that crews had to keep rebuilding track as coyotes gnawed away the rawhide are complete fiction.

Locomotives from Pittsburgh

In late 1871, Baker traveled to the East Coast to look at other railroads. He studied narrow gauge railroad construction, especially those that used wooden rails. While in Pittsburgh, he bought two engines made by Porter, Bell & Company. These 0-4-0 engines weighed about 7.5 tons and cost $4,400 each. The engines burned wood and carried a water supply in a tank on top of the boiler. He named Engine No. 1 the Walla Walla and Engine No. 2, the Wallula.

The two engines were delivered by sailing ships that sailed around Cape Horn and up the west coast to the mouth of the Columbia. From there, they were placed on steamers. The locomotives arrived on March 11, 1872.

Construction began in 1872, and the road was built west from Wallula. Baker placed Major Sewell Truax in charge of grading the roadbed, and the crew began the work in March. The town of Wallula boomed due to incoming and outgoing shipments by the railroad. Wallula soon had a hotel, ice house, warehouse, butcher shop, several saloons, several stores, a doctor’s office, corrals, a livery, and a boardinghouse.

Baker had to find a timber source for ties and rails. He studied the Yakima, Clearwater, and Grand Ronde rivers. For a short time, he used trees floated down the Grande Ronde River. One man drowned in a log jam, and then almost all the logs were lost down the river. This route cost about $1 per log, three or four times more expensive than logs from other sources. Logs floated down the Yakima and Clearwater rivers were more likely to reach their destination, but only in small quantities.

Early in 1872, Baker hired loggers to cut timber on the upper Yakima River. The river was low at the time, but they were able to float down some logs in October and November to Wallula. Baker had opened a sawmill at Wallula earlier in the year. His son Frank supervised the mill, which cut ties and the wooden rails for the railroad. He milled the first ties on November 11, 1872.

Building the Railroad

Once the roadbed was graded and ties and rails were milled, crews went to work laying track. They laid ties on the roadbed and then laid the wooden rails on top of the ties. Then they secured a strap of iron one-half inch thick by two inches wide to the top of the rail. They drove spikes through the iron to hold it to the wooden rails. Then they bent the ends of the iron over the ends of each rail to help prevent the iron from curling up from friction by locomotive wheels. This didn’t always work; sometimes the iron worked its way loose and sprang up through the floorboards of the train cars. To prevent such “snakeheads,” engineers traveled very slowly over the rails.

Baker was known as a hard taskmaster. He toured the line at least twice each week to check its progress. He took periodic trips to the upper Yakima to check on the logging. There were frequent injuries and sickness in the camps and he always took medical remedies with him. Baker himself, who was 48, suffered poor health. He had suffered a stroke, which left one arm partially paralyzed.

The workers respected Baker because he worked as hard as anybody. However, they still felt they did not get paid enough for the conditions they had to endure. Sometimes the wind was so severe that men had to get up in the middle of the night to prop up the flimsy bunkhouses. Sand often buried the tracks and the men would have to dig out the rails before they could begin the day’s work. They later built barricades around their work to keep out the dirt. They also complained about poor food. Eventually the workers struck and Baker responded by firing the ringleaders. He did make one concession, which was to hire new cooks.

Even so, he always looked for ways to save money. He did not build water tanks along the route, but instead crews had to take water from the river and streams with buckets. Frank Baker kept a sheep dog on the train to chase away cows that strayed onto the tracks. Initially he bought no passenger cars, so people rode on top of the grain sacks on flat cars. Eventually he had a passenger car built at the Wallula mill, nicknamed “The Hearse.” It had only small windows with benches along the sides.

Early in 1873, crews reached the halfway point. Baker thought he could get some support from the citizens now that they were seeing his progress and getting some benefit from the railroad, even though it wasn’t even finished. But another bond issue failed and he still was stuck financing it himself. In the meantime, people didn’t hesitate to take their crops by wagon to the end of the track to ship via the next steamer that left Wallula. By then, the Oregon Steam Navigation Company made regular, almost daily, stops at Wallula.

About this time, Baker received an order of regular iron rails that he imported from Wales. He used these rails on curves and steep grades where the rails would take the most stress.

Financial panic in 1873 slowed construction, but by March 1874, 16 miles of track were completed up to Touchet. By the end of that year Touchet farmers shipped 4,000 tons of wheat and received 1,100 tons of merchandise. By the end of 1874, the tracks reached Whitman Station, 10 miles from Walla Walla. Another locomotive, the Columbia, would soon be pressed into service.

Arrival in Walla Walla

In the fall of 1875, the track finally reached the city of Walla Walla. The final cost of the railroad was $356,134.85, including the new iron rails, which lined most of the route by this time. During construction, 9,155 tons of wheat shipped from Wallula. During this time, Baker received an annual salary of $2,400, payable in company stock.

On that memorable October day, Dr. Baker offered anyone who wanted a free round trip on the train. It took two and a half hours each way to complete the 32 miles between Walla Walla and Wallula on a beautiful fall day. “The Hearse” was completely full, so additional flatcars were pressed into service. Baker went from car to car, escorting ladies to seats and making sure everyone was comfortable. The train reached Wallula by noon. Baker and his friends helped the ladies descend from the cars. He had picnic hampers at the ready. As if it was participating in the celebration, the steamer Colonel Wright arrived to load a shipment of wheat.

The sky was clear as people unpacked their lunches near the old adobe fort. After lunch, Bill Green led the people in a cheer for Baker. The people called for a speech. Baker reluctantly stood up. He spoke of the great accomplishment of building a railroad. He told the crowd about two other engines he had ordered named the Blue Mountain and the Mountain Queen. Another engine, the J. W. Ladd, would be the sixth Porter engine to serve the railroad. He also promised to build a good passenger coach. Afterward, his friends gathered around him to offer personal congratulations. Then people got back on the train and rode back to Walla Walla.

In 1876, the townspeople became disenchanted with Baker. He had set $5.50 per ton as the charge for freight. The townspeople thought this was too high, though it was still less than wagon freighters charged. They figured he was getting even because they had not financially supported the building of the railroad. Townspeople discussed digging a canal from the Whitman Mission to Wallula so they could ship merchandise by boat. Some tried using the freighters, who reduced their rates to compete. Both schemes were hopeless. In 1876, 16,766 tons of wheat shipped to Wallula via the Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad. In 1877, 28,806 tons of wheat were shipped.

There were few accidents or injuries associated with building the railroad. It wasn’t until regular operation commenced that a serious accident occurred on August 31, 1877. Just as the train crossed a 40-foot high trestle, it jumped the track. The engine reached the other side, but the next eight cars crashed over the trestle. Fortunately, there were only four men on board and none of them were hurt.

In 1879, Baker sold most of his company stock to the chief stockholders of Oregon Steam Navigation Company, which was later absorbed by Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. A year later, he sold his remaining stock to Henry Villard. Villard extended the line southeast into Oregon and west from Wallula to Umatilla, Oregon. In 1881, he converted the line to standard gauge to meet the new Northern Pacific line being built east from Portland.