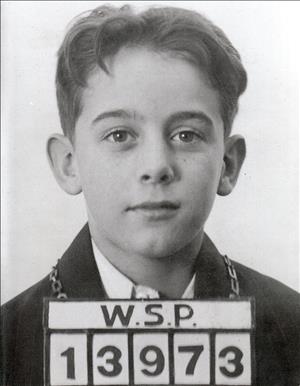

On August 5, 1931, 12-year-old Herbert Niccolls Jr. (1919-1983) shoots and kills Asotin County Sheriff John Wormell (1859?-1931). The case attracts national attention. Niccolls receives life in prison at the state penitentiary in Walla Walla, but is pardoned in 1941. He goes on to live a successful, crime-free life before dying in 1983. Wormell remains the only officer in Asotin County as of today (2006) to lose his life in the line of duty.

A Harsh Childhood

Twelve-year-old Herbert Niccolls Jr., had lived a hard life before August 5, 1931. Believed to have been born in Boise in 1919, he lived in several foster homes and later at the St. Anthony Reform School in southeastern Idaho during the 1920s. By age 12 he had committed a series of offenses, including setting fire to a church and multiple counts of theft.

By his 12th birthday in June 1931, "Junior," as the boy was called, was living in Asotin with his paternal grandmother, Mary Addington. Addington was a strict disciplinarian who, by some accounts, routinely beat Herbert with a club for the slightest infraction. On August 4, Niccolls ran away from his grandmother's home, carrying a .32-caliber Iver-Johnson pistol that he had recently stolen.

The Shooting

About 1 a.m. on August 5, Niccolls broke into Peter Klaus's People's Supply Store in Asotin, intending to steal candy and cigarettes. But within minutes Sheriff John Wormell knocked on the door at the front of the store. Wormell was a 72-year-old former state representative, four-term sheriff, and descendant of one of the first settlers in Asotin County. "Come on out," he said. "I am the sheriff of Asotin County" (Lewiston Tribune).

Receiving no response, Wormell entered the store. With him was Peter Klaus, the store owner. Waiting outside were Deputy Charlie Carlisle and Deputy Sheriff Wayne Bezona. Wormell and Klaus began to search the store. Someone turned on the light. Niccolls, hiding behind a vinegar barrel, panicked. He jumped to his feet and fired at Wormell, who was standing less than five feet away. The bullet struck Wormell in the head, killing him instantly: "Wormell fell in his tracks without an outcry, his gun in his hand" (Lewiston Tribune).

Arrest and Trial

Niccolls was taken to the Asotin County Jail. However, Deputy Sheriff Wayne Bezona, fearing the boy might be taken from the jail and lynched, quickly moved him to the Garfield County Jail in Pomeroy, nearly 40 miles away.

Niccolls, at four feet, eight inches, and 60 pounds, looked even younger than age 12. He became known as the barefoot boy murderer, as he was barefoot when he shot the sheriff. Reports claimed that he had not owned a pair of shoes in two years.

With the exception of a brief return to Asotin on September 3 for his arraignment (he pled not guilty due to mental irresponsibility), Niccolls remained in Pomeroy until his trial.

The trial began in Asotin on October 26, 1931. For Asotin County, it was the trial of the century. The courthouse was full, and the Methodist Church down the street sold fried chicken lunches to the crowd. Dozens of reporters from various newspapers shouted questions at Niccolls as he walked from the police car into the courtroom.

During the trial Clarkston attorney Ed Doyle argued that Niccolls was not guilty due to insanity. Prosecutor Elmer Halsey rebutted Doyle's argument by producing a doctor as an expert witness who testified that Niccolls was a constitutional psychopath, but not insane. "This type, because of their high intelligence, are extremely dangerous. They are not safe to be at large. They can never recover because of an inherited trait" (Lewiston Tribune). Even Niccolls's grandmother, testifying on his behalf, hurt his case by testifying that she believed him to be possessed by a demon.

The case went to the jury on October 27. After deliberating for three hours, the jury returned a guilty verdict. Although the prosecution had asked for the death penalty, the following day Judge Elgin Kuykendahl sentenced Niccolls to life in prison. Niccolls became the youngest person in the state of Washington to receive a life sentence and was sent to the state penitentiary in Walla Walla.

Supporters and Detractors

Father E. J. Flanagan, the founder of Boys Town in Omaha, Nebraska, was moved by an account he read of the trial and conviction. He mounted a public campaign and gave a speech on Niccolls's behalf on national radio on the night of November 12. Flanagan urged his listeners to write to Washington Governor Roland Hartley and ask that Niccolls be paroled to Boys Town, and many did. Hartley was said to have bitterly resented the pressure.

Also joining in the call for Niccolls's parole was Armene Lamson of Seattle. She was a prominent member of Seattle society and a devoted crusader for child welfare. She successfully urged Flanagan to visit Seattle to argue his case. Flanagan spoke at a dinner at the Washington Athletic Club and promised to personally supervise Niccolls's training and education if he came to Boys Town.

In Asotin, sentiment was decidedly against Niccolls's early parole: The Asotin Chamber of Commerce issued a proclamation asking that he not be freed under any circumstances, and the Asotin Town Council made a similar resolution. Wormell's family took no stand on the matter.

On December 20, 1931, Governor Hartley denied the request for Niccolls's parole. When Clarence Martin was elected governor in 1932, Flanagan and his supporters hoped that the new governor would parole Niccolls to Boy Town.

Martin did not immediately parole Niccolls when he assumed office in 1933. But he did take a more personal interest in the case than Hartley had. Martin began visiting Niccolls in prison and followed his case through the 1930s.

Life in Prison

Niccolls flourished in the structured prison environment. He became an avid reader and was gifted in math. He received homework weekly from the Walla Walla School District, and in 1938 received his high school diploma. He subsequently took correspondence classes from Washington State College while still in prison.

Governor Martin pardoned Niccolls in 1941. During most of his 10 years in Walla Walla, Niccolls had not been kept with the general population. Initially kept in a prison cell, he later stayed in a specially built hut built near a guard tower, where he was alone at night, separated from the other prisoners. He ate his meals with officers instead of inmates, did not have to wear the denim prison uniform, and received tutoring from other prison inmates.

After a brief, unsuccessful start at a bakery job just after his release from prison, Niccolls worked in the accounting department of a Tacoma shipyard, and there he excelled. He subsequently moved to California and joined the accounting department at MGM, and later worked for 20th Century Fox in Hollywood. He married and had a son, John.

Herbert Niccolls died of a heart attack in 1983, having lived a crime-free life since his parole 42 years earlier.