Walla Walla County covers 1,271 square miles in south central Washington, ranking 26th in size among Washington's 39 counties. It is bounded to the east by Columbia County, to the north by the Snake River and Franklin County, to the west by Benton and Franklin counties and the Columbia River, and to the south by the state of Oregon. The city of Walla Walla is the County Seat. The land that would become Walla Walla County was one of the earliest areas between the Rocky Mountains and the Cascade Mountains to be permanently settled by non-Indians, and for that reason it is sometimes referred to as the cradle of Pacific Northwest history. The 1847 Whitman Massacre and the 1855 Treaty Council in Walla Walla are among the most significant events to have occurred within what is now Walla Walla County. Agriculture is the most significant industry in the county, especially the cultivation of wheat, onions, and wine grapes. Walla Walla County has a population of 54,200 as reported in the 2000 Census.

Early Days

Walla Walla, written "Wolla Wollah" by Lewis and Clark, derives from a Nez Perce and Cayuse word "walatsa," meaning running, a probable reference to the running waters of the Walla Walla River. The area enjoys Chinook winds that usually yield relatively mild winters. Abundant grass and water for cattle were early inducements to white settlement.

The western part of Walla Walla County is flat grasslands, giving way to gentle rolling hills in the central portion of the county. As the eastern part of the county approaches the Blue Mountains the terrain becomes increasingly steep and less suited to agriculture, although wheat and green peas are cultivated at elevations as high as 3,000 feet. The county's principal tributaries of the Columbia River, the Walla Walla and the Touchet (which flows into the Walla Walla), originate in the Blue Mountains in Columbia County and flow west across the county, converging with Mill Creek and Dry Creek near the town of Touchet.

The Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla peoples occupied the land at the eastern end of the Columbia River basin. The tribes lived in semi-permanent lodges up to 60 feet long. These lodges were shared by up to 10 related families. The three tribes spoke the Sahaptin language and also shared the neighboring territory with members of the Nez Perce tribe. The Cayuse and Nez Perce acquired horses in the early 1700s, breeding them for sale and trade with each other and, after white contact, with trappers and eventually early settlers.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition passed what would become the northern border of the county when as they canoed down the Snake River, which they called the Lewis River, in October 1805. On their return voyage the Expedition left the Columbia River near present-day Wallula to begin their eastern trek across the continent.

The Era of Fur Trading

The North West Fur Company (Canadian) and the Pacific Fur Company (initially owned by American John Jacob Astor, but later bought by the British) reached the area soon thereafter, later followed by the Hudson's Bay Company (British). Walla Walla was an important center for fur trading within the region. The Cayuse, eager to increase their opportunity to trade, encouraged these developments.

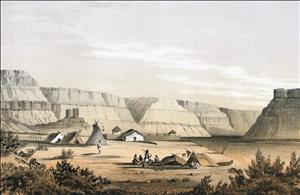

In 1818 the North West Fur Company built Fort Walla Walla (initially known as Fort Nez Perce) half a mile from the mouth of the Walla Walla River on the east bank of the Columbia River. The timber to build the fort was floated down the Walla Walla River from as much as 100 miles away. The resulting fortress was so formidable that the fort's first factor, fur trader Alexander Ross, called it the Gibraltar of the Columbia. In 1821 the Hudson's Bay Company merged with North West Fur, bringing this important early fort under Hudson's Bay control.

Contemporary drawings and letters by early visitors to the vicinity, including missionary W. H. Gray (1810-1889), indicate that this fort no longer existed by 1831 and that it had been replaced with another less substantial fort made of driftwood from the Columbia. This second fort burned down in 1841 and was rebuilt of adobe made from nearby clay combined with wild rye grass. Fort Walla Walla was abandoned during the Indian Wars of 1855, but remained standing until about 1894 when it was destroyed by flooding. This site later became the town of Wallula, and in 1952 was submerged for the construction of the McNary Dam.

Between 1855 and autumn of 1858 during the Indian Wars settlers were banned from the region. In 1856 the United States Military established a new Fort Walla Walla as a military post. This post was also known as Steptoe Barracks, after commander Colonel Edward Steptoe (1816-1865), and was located where the Nez Perce Trail forded Mill Creek in what became the city of Walla Walla. This location is now (2006) the site of a Macy's department store housed in the former Liberty Theatre building at 54 East Main Street in Walla Walla. In 1858 the 1856 structures were abandoned and operations moved about one and one-half miles southwest.

Between 1858 and 1900 a number of buildings were constructed as part of the Fort Walla Walla complex. Fort Walla Walla was closed in 1910 and in 1921 the facility was converted into a Veteran's Hospital. In 1996 the hospital at this facility was named the Jonathan M. Wainwright Memorial Veterans Affairs Medical Center after World War II Congressional Medal of Honor winner General Jonathan M. Wainwright IV (1883-1953) who is believed to have been born in Fort Walla Walla officer quarters.

Missionaries and Missions

On September 12, 1836 Presbyterian missionaries Marcus (1802-1847) and Narcissa Prentiss Whitman (1808-1847) and Henry (1803-1874) and Eliza Hart Spalding (1807-1851) arrived at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. After exploring the nearby vicinity, the Spaldings founded a mission at Lapwai among the Nez Perces in present-day Idaho. The Whitmans founded the Waiilatpu mission on the Walla Walla River near Fort Walla Walla. For the next 11 years Marcus and Narcissa Whitman proselytized to the Cayuse, cultivated an apple orchard and extensive gardens, wrote missives home that ultimately resulted in increased immigration to the area, and served as the important beacon and way station for the earliest pioneers beginning to carve their way West overland.

On November 29, 1847, distraught over a measles epidemic that was decimating their families and by recent killings of Cayuses by whites, an undetermined number of Cayuse killed the Whitmans and 12 other white settlers and took more than 50 others hostage. Catholic Bishop Augustin Magloire Blanchet (1797-1887) and Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson's Bay Company helped negotiate the release of the hostages after a month of captivity. The killings and hostage-taking burned deeply into the white settlers' psyches, both confirming and inflaming their fears of Indian violence and giving the United States government license for long-lasting reprisals against the Cayuse and other tribes.

Over the subsequent decades and up through the present time the phrase "Whitman Massacre" became shorthand for the brutal cost of forcing change on members of an established civilization who had little taste for their supposed salvation. At the time of the massacre the British government had ceded the land south of the 49th parallel (including Waiilatpu) to the United States but the area had not formalized a Territorial government. On August 13, 1848, largely as a result of the public outcry when word of the Whitman Massacre reached Washington, D.C., Congress created Oregon Territory.

From the time of the massacre until June 3, 1850, when five Cayuses who had voluntarily gone to Oregon City were subjected to a trial that was largely or wholly sham, and executed for the Whitman murders, volunteer militias fought the Indians. This conflict was later called the Cayuse War. The Cayuse who were hanged for the murder of Marcus Whitman (the only charge tried) all admitted being present at Waiilatpu on the day of the massacre but at least one of them and very likely more denied participating in any killing. They were not called to testify on their own behalf. Their names were Telokite, Tomahas, Clokomas, Isiaasheluckas, and Kiamasumkin.

Boundaries and Treaties

Washington Territory was established on March 3, 1853, and Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862) appointed Territorial Governor. Skamania County, established by the first Territorial Legislature on March 8, 1854, encompassed the future Walla Walla County.

Only a few weeks later, on April 25, 1854, Walla Walla County was divided off from Skamania. This first version of Walla Walla County was enormous, encompassing half of what is now Washington, all of Idaho, and about a fourth of Montana. The county seat was placed at Waiilatpu on the claim of a settler named Lloyd Brook, but the Treaty Council at Walla Walla in May 1855 and the Indian Wars that followed prevented the county infrastructure from being organized in anything more than name.

On May 29, 1855, Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens convened the First Walla Walla Council with members of the bands and tribes of the Yakama, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Cayuse. The treaty council was held on Mill Creek near the present city of Walla Walla, although changes in the creek's course over time make it difficult to pinpoint the exact spot. When the council was concluded, tribal leaders had signed a treaty relinquishing the vast majority of their land and agreeing to be settled on reservations, but the Yakama quickly rethought after Stevens immediately failed to honor the waiting period he had promised to observe before advertising the land for white settlement. The conflicts that followed, now known as the Yakama Indian Wars, were brutal and resulted in great loss of life among the tribes. The Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Cayuse tribes ceded more than six million acres of land.

On January 19, 1859, the Territorial Legislature passed an act creating a true infrastructure for Walla Walla County. In the November 17, 1859, election, Walla Walla was chosen the county seat. In 1865, 1870, 1872, and 1876 the Oregon state legislature made repeated but unsuccessful bids to have the United States Congress separate Walla Walla County from Washington and make it part of Oregon. Old Walla Walla County was by this time being regularly reduced in size as new counties and territories were carved out of its enormous land mass. On November 11, 1875, Columbia County was established and with it the final boundary change of Walla Walla County.

In the spring of 1859 the United States Congress ratified the treaties creating the Yakama, Nez Perce, and Umatilla tribal reservations. Even before these treaties were ratified, white settlers began streaming into the region to stake claims. W. D. Lyman's History of Old Walla Walla County, published in 1918, called these individuals "the impatient immigration" (p. 109). Many of those who filed land claims had in fact been soldiers or volunteers in the United States Army's effort to quell the Indian uprising and clear the way for white settlement.

In 1859 gold was discovered on the Clearwater River in (present-day) Idaho. As the main supply point for hopeful miners, the city of Walla Walla quickly attracted miners, freight packers, bankers, and merchants of all kinds eager to supply the miners. One Walla Walla pack-animal supply firm even used a stable of six camels (originally imported by the United States Army for use in the Southwestern United States and later sold) to transport miners' supplies. Profits ran high, with staples like coffee and cured meat selling for as much as four times their price in Portland.

The gold rush also stimulated the local market for farm produce and beef cattle. By 1861 the city of Walla Walla had a population of 3,500, making it the largest community in Washington Territory at the time. By the late 1860s gold deposits were largely depleted, ending Walla Walla's boom days, although Seattle's population did not surpass Walla Walla's until the early 1880s.

Whitman College

Whitman Seminary was founded by Presbyterian missionary Cushing Eells (1810-1893) in 1859 and named in memory of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. On December 20, 1859 the Washington Territorial Legislature awarded the first educational charter in Washington Territory to Whitman Seminary.

The school first held classes on October 15, 1866, and only sporadically thereafter due to financial difficulties. In 1882 the trustees of the college changed the institution's name to Whitman College in 1882 and on November 28, 1883, the Legislature issued it a new charter establishing Whitman College a four-year, degree-granting institution.

A private college, Whitman has from its inception been nonsectarian. In 1913 the school became the first institution of higher learning in the nation to require that undergraduate students complete comprehensive examinations in their major field in order to graduate, and in 1919 Whitman installed the first chapter of Phi Beta Kappa in any Northwest college. Founded in 1776, Phi Beta Kappa is the oldest and most respected undergraduate honors organization in the United States.

On November 10, 1869 Baker Boyer National Bank opened its doors in Walla Walla, becoming the first bank in the future state of Washington. As of 2006 Baker Boyer remains in business, still independently owned and an integral participant in Walla Walla County's history.

Agriculture

Farmers in Walla Walla County found grain crops -- winter and spring wheat, oats, and barley -- well-suited to growing conditions. The first flour mill in the county was built by A. H. Reynolds, J. A. Sims, and Captain F. T. Dentin in 1859. The coming of the railroads enabled farmers to easily transport their grain and other crops to market, and Walla Walla County wheat was shipped from Portland around Cape Horn and on to Liverpool, England. Field crops such as corn also began to be produced on a small commercial scale during the 1860s.

James Foster planted the first orchards in the county in 1859. A. B. Roberts and nurseryman Phillip Ritz followed suit, and by 1880 there were 400 acres of apple and pear orchards in the county. By 1900 this had increased to nearly 3,000 acres.

Working on the Railroad

In 1871 Walla Walla merchant and physician Dorsey Syng Baker (1823-1888) began building the region's first railroad to connect Walla Walla with the Columbia River. The 30-mile line, called the Walla Walla and Columbia River Railroad, was completed on October 23, 1875.

Lacking iron or steel for rails, Barker used timber from the upper Yakima Valley tied into rafts and floated downstream to near Wallula. There the timber was milled and cut into 16-foot rail sections, then surfaced with two-inch-wide strap iron. Baker's railroad was also known as the Rawhide Railroad, owing to an apocryphal story claiming that leather strips, not iron, held the rails together.

In 1879 railroad magnate Henry Villard (1835-1900) purchased it and it became part of Villard's Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company. This company also included the Oregon Steam Navigation Company's 14 Columbia River steamers. The line was extended west to Portland in 1881 and 60 miles north to connect with steamboats on the Snake River in 1882. The Northern Pacific Railroad construction reached Walla Walla County in 1883, connecting the county with Puget Sound via Stampede Pass in 1888.

The State Penitentiary

The Walla Walla State Penitentiary opened in the city of Walla Walla in 1887 as a territorial prison. Inmates labored in the prison's brick yards, in a jute mill making grain bags and rugs, and in later years making license plates and highway signs.

Walla Walla Penitentiary inmates also produced clothing and mattresses and operated a cannery and dairy for use in various state institutions. Walla Walla State Penitentiary is the state's major penal institution, with minimum-, medium-, and maximum-security areas. The Washington State Department of Corrections is a significant employer in Walla Walla County.

Lower Snake River Dams

On November 1, 1948, the United States Corps of Engineers' Walla Walla District officially opened. The Walla Walla District was charged with developing dams on the lower Snake River. Over the next 30 years these dams were destined to be a flashpoint for environmentalists and a case study for Americans' changing attitudes toward the environmental, physical, and financial costs of hydroelectric dams.

The Lower Monumental Dam (backed by Lake Herbert G. West and operational since 1969) and the Ice Harbor Dam (backed by Lake Sacajawea and operational since 1961) dam the lower portion of the Snake River as it flows along the northwestern border of Walla Walla County. The Marmes Man rockshelter, considered the most important of the archeological sites flooded by dams on the lower Snake River, lies beneath Lake Herbert G. West.

The County Today

Walla Walla County has only four incorporated cities: Walla Walla, Prescott, College Place, and Waitsburg. Unincorporated towns include Ayer, Burbank, Calhoonville, Dixie, Eureka, Lowden, Touchet, and Wallula.

Farming, manufacturing (especially food-related), higher education, and government employment are important industries in the county. Wheat is the county's largest crop. Broetje Orchards in Prescott is one of the largest privately owned orchards in the world with 5,000 acres of apple trees in Prescott, Benton City, and Wallula. Walla Walla has a growing wine industry and, as in Yakima and Benton counties, wine tourism is a rapidly increasing part of the county's economy. Walla Walla Sweets, a locally grown variety of sweet onion with a low sulfur content and high water content, are exported widely and serve the county as a simple but eponymous ambassador of Walla Walla County's agricultural bounty.