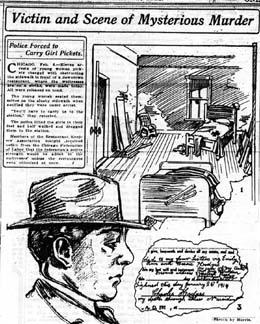

On March 31, 1914, Charles Hopkins (1888-1948) is arrested in a rooming house at Van Horn in Skagit County for the murders of Antone Olson and Tony Greb and the attempted murder of John Freeman, near McMurray. Law enforcement officers throughout Western Washington have been hunting for him since February 6, 1914, for a murder in Seattle. Hopkins is arrested in Everett on March 26, 1914, but manages to escape, shooting a policeman and two civilians in the process. With the words “TRUE LOVE” tattooed on the backs of his fingers, he is easy to identify. The newspapers variously call Hopkins the “Tattooed Bandit” or the “True Love Bandit,” and, because of the ruthlessness with which he kills, the “second Harry Tracy.” A Skagit County jury will convict him of first-degree murder on June 15, 1914, and, because the death penalty had been abolished in 1913, he will be sentenced to life in prison. Charles Hopkins, age 60, will die at the state penitentiary in Walla Walla on March 6, 1948.

Charles Hopkins was born in England and ran away to sea at age nine. While working on board a ship, Hopkins fell in love with the captain’s daughter and had the name “Ethel,” entwined with vines, flowers, and butterflies, tattooed on his right wrist and her likeness on his right arm. He also had the words “TRUE LOVE” tattooed on the fingers of his hands just below the knuckles. In 1906, Hopkins decided to stay in the United States and found employment with a boilermaker in Wisconsin. He worked there for one year until the company went bankrupt; then, he became a hobo, migrating eventually to Washington state.

In April 1909, Hopkins was arrested in Ellensburg for burglary and sentenced to serve 14 years in the Washington State Penitentiary at Walla Walla. He was released in November 1913 under executive pardon and went to Victoria, B.C., Canada. There, he was arrested for illegal entry, fraternizing with known criminals and carrying concealed weapons. He was eventually released from jail, but ordered expelled from Canada. Hopkins gave Canadian Immigration officers the slip and headed for Seattle, arriving on Monday, February 2, 1914.

Murder

On Friday morning, February 6, 1914, Mr. Sazao Yamana, proprietor of the Hotel St. James, 209 Washington Street, notified Seattle Police that the maid had discovered a severely injured man in one of the rooms. Sergeant William Donlan and Patrolman C. E. Francis found Charles Hodges, age 28, from London, England, lying on the floor unconscious in a pool of blood. A heavy wooden bed slat had been used to beat him and fracture his skull. Police found Hodges’ pockets empty, but based on a recent bank receipt, believed he had been robbed of approximately $20. Following an unsuccessful operation, Hodges died at City Hospital later that afternoon. With “TRUE LOVE” tattooed on the backs of his fingers, it didn’t take detectives long to identify the assailant as Hopkins, the man who had been accompanying Hodges for the last few days. Yamana and several roomers at the Hotel St. James identified his picture. Police put out a dragnet for Hopkins, but he had already fled the city.

On Thursday night, March 26, 1914, Hopkins and Paul Putnam, from Brewster in Okanogan County, were arrested on Grand Avenue in Everett for suspicious behavior and loitering. As Patrolman Lee Williamson was opening a call box to summon the patrol wagon, Hopkins snatched his service revolver. In the scuffle for the weapon that followed, Hopkins shot Williamson and two citizens who tried to assist the patrolman: Cyrus Robinson and Donald Shallcross. The three wounded men were taken to Providence Hospital and Putnam surrendered himself to police, claiming he didn’t know the assailant. Betrayed by his tattoos, Hopkins was quickly identified as the man wanted in Seattle for robbery and murder. Putnam, revealed as a criminal and in possession of a gun, was sent to the Snohomish County jail for 30 days on a vagrancy charge.

Early Friday morning, March 27, 1914, Hopkins stopped at Charles A. Blackman’s sawmill in North Everett and robbed the night watchman and a mill worker of their money and clothing. After asking directions to the nearest town north of Everett, he disappeared into the early morning gloom. Although police guarded all the bridges and railroad tracks, they were unable to find Hopkins.

On Saturday, March 28, 1914, a Great Northern Railway conductor reported seeing a man walking along the railroad tracks near Halford, 45 miles east of Everett (Stevens Pass Highway, U.S. Route 2) and identified a photograph of Charles Hopkins. Other witnesses said that a man who looked like Hopkins had asked direction to the Ferry-Baker Lumber Company plant near Marysville.

Early Saturday evening, three loggers, Antone Olson, Tony Greb, and John Freeman, were walking along the Northern Pacific Railroad tracks near the Ehrlich Station, two miles north of McMurray when they were waylaid by a lone bandit. The loggers were forced at gunpoint to cross a logjam over Ehrlich Creek and taken into the trees. After clubbing them unconscious with the butt of his gun, the bandit searched the loggers for money but found only 45 cents; then, he shot them several times and dragged their inert bodies into a nearby marsh.

Early Sunday morning, March 29, 1914, Freeman regained consciousness, crawled across the logjam and a quarter-mile up the railroad tracks to a shack near Ehrlich Station. There, he awakened Joseph Kelly, Thomas Dunning, and Fred Carson, and told them what had happened. Kelly went to McMurray and spread the alarm. City Marshal Walter Hinman took a railroad speeder (handcar) to Ehrlich, collected Freeman and took him to Doctor H. L. Miller’s hospital at McMurray. On the way back, Marshal Hinman found Olson’s body hidden behind a log, but there was no sign of Tony Greb.

At the hospital, Doctor Miller found that, in addition to a severe concussion, Freeman had been wounded in the neck and thigh. When conscious, Freeman told Marshal Hinman that the bandit had tattoos on the backs of his fingers and identified a photograph of Charles Hopkins as the assailant. Posses were organized throughout Skagit and Whatcom Counties to search for the killer and more than 200 armed deputies watched the railroad tracks and every train station, road, and trail between McMurray and the Canadian Border. The newspapers and every town, construction camp, and logging camp in the area were given pictures and a description of Hopkins. Search parties combed the area around Ehrlich Creek for Tony Greb’s body, but it was never found. All they discovered were two bloody pieces of hard, black rubber, broken from the grips of a revolver, at the scene of the crime. Marshal Hinman speculated that Greb may have escaped while being marched into the trees.

Meanwhile, Hopkins made his way north across the Skagit River to Sedro-Woolley; then, he was given a ride on a milk truck, nine miles east to Lyman (North Cascades Highway, State Route 20). He stayed Saturday night at Bales and Elizabeth Wiseman’s farm and, after breakfast the next morning, continued heading east, up river.

On Monday, March 30, 1914, both the Snohomish County and Skagit County Sheriff’s Offices posted a $500 reward for the capture of Charles Hopkins, dead or alive. There were several reports that Hopkins had been seen in Mount Vernon. Two women claimed that a man with a gun entered their kitchens early in the morning, demanding hot coffee and breakfast. At about noon, there was a report that Hopkins was seen leaving Mount Vernon and was hiding near the bend in the Skagit River. Posses surrounded and searched the area, but found no trace of the fugitive.

Late Monday evening, Hopkins stopped at Frank Yeager’s farm near Van Horn on the upper Skagit River, asking for food and lodging. Yeager took him to the general store and rooming house at Van Horn where the proprietor, Clark Ely, rented Hopkins an upstairs room. Recognizing the killer from his description in the local newspaper, Yeager went to fetch City Marshal Joseph E. Glover at Concrete, while Ely stood watch. Marshal Glover organized a large posse and about 1:30 a.m., quietly surrounded the building. Using a passkey, Marshal Glover entered the room alone and quickly handcuffed Hopkins while he was asleep. He began to struggle, but was overpowered by other men entering the room.

Hopkins was in possession of four handguns, including a .38-caliber revolver with broken rubber grips, and a supply of ammunition. The noses of lead bullets had been scored crosswise, reported to be a Hopkins trademark, making them into deadly dum-dums (expanding bullets).

Immediately after capture on Tuesday morning, March 31, 1914, Hopkins was taken, under heavy guard, to the jail in Concrete. The fugitive was kept manacled and under guard at all times, even during meals, to discourage any escape attempts. Fearing a possible lynch mob, Skagit County Sheriff Edwin Wells sent sheriff’s deputies to escort Hopkins to Mount Vernon by train. But, Hopkins was more of a curiosity than anything and scores of people gathered in Concrete and Mount Vernon to see the man the newspapers variously called the “Tattooed Bandit,” the “True Love Bandit,” and the “second Harry Tracy” because of the ruthlessness with which he killed.

On Wednesday, April 1, 1914, Chief Prosecutor Charles D. Beagle formally charged Charles Hopkins in Skagit County Superior Court with the first-degree murder of Antone Olson and the attempted murder of John Freeman. Sheriff Wells remarked to the press, “I honestly believe that he (Hopkins) is without fear, without remorse, a man with a body clean and strong, a mind alert, but whose soul has died” (The Seattle Star).

On April 16, 1914, Hopkins entered a plea of not guilty at his arraignment before Judge Egbert Crookston. The preliminary hearing was held in the judge’s chambers to avoid any possible demonstrations. Freeman was brought from the hospital at McMurray to testify about the assault and to identify Hopkins and some items stolen from his person, which included a distinctive straight razor. Following the hearing, Hopkins was remanded to the custody of the Skagit County Sheriff. A trial date was set for June 12, 1914.

While awaiting trial, Skagit County Jailer William Bardsley discovered that Hopkins was making a fake gun. He had stolen a teaspoon from his lunch tray and made a small saw from the handle with his nail file. Hopkins removed the seat from a wooden chair, then covered the hole with old newspapers to prevent detection. Using the saw, nail file, and the top from a tin can, he began carving. He planned to wrap the replica with tinfoil saved from his tobacco cans, to give it a realistic appearance; then, some dark night, threaten Jailer Bardsley and attempt an escape. Sheriff Wells happily allowed Hopkins to occupy his time with the project for a few weeks before confiscating the wooden gun.

Trial began on Friday, June 12, 1914, in the Skagit County Courthouse before Superior Court Judge Jessie P. Houser. Local newspapers had given the murder at Ehrlich Creek so much publicity that it took two days and three venires to impanel an impartial jury. It took only two more days to present the case. In closing arguments, Prosecutor Beagle told the jury that Hopkins had been caught practically “red-handed.” He was in possession of the murder weapon and several items belonging John Freeman, a victim and an eyewitness, who positively identified Hopkins as the killer.

Defense Attorney Vernon Branigan argued that Olson and Freeman were shot by an ex-convict known only as “Dago Frank,” a sworn enemy of Hopkins from the Washington State Penitentiary. During the trial, Hopkins testified that, as he neared the place where Olson was killed, he heard gun shots and saw “Dago Frank” emerge from the underbrush. He followed “Dago Frank” and the next morning, found him asleep by a campfire. Hopkins said he killed “Dago Frank” in a gunfight and threw his body into Lake McMurray. The murder weapon, found in Hopkins’ possession, actually belonged to “Dago Frank.”

The case was concluded on Monday afternoon, June 15, 1915 and went to the jury. After deliberating for 26 minutes, the jury found Hopkins guilty of first-degree murder and assault with intent to commit murder. As he left the courtroom, Hopkins, who had been uttering threats throughout the trial, said to Prosecutor Beagle, “I’ll get you for this” (Bellingham Herald). Several jurors told newspaper reporters that it was a shame Washington had abolished the death penalty in 1913.

On June 25, 1914, Judge Houser sentenced Hopkins to life at hard labor in the Washington State Penitentiary, adding that also he must pay for court costs. Hopkins, jingling some coins in his pocket, said “How much are the costs? I might as well pay for ‘em right now” (Mount Vernon Herald). Under heavy guard, Hopkins, handcuffed and chained to three other prisoners, left Mount Vernon on the 1:00 p.m. passenger train for Walla Walla.

Charles Hopkins, age 60, died on March 6, 1948 at the Washington State Penitentiary. He never confessed to his crimes, declaring that society made him a criminal.

When Hopkins left the Skagit County Jail for the state penitentiary, he left behind a poem for Sheriff Wells and Jailer Bardsley entitled “Hopkins Lament,” which was published in local newspapers.

Hopkins Lament

The nineteenth of May, I cannot forget,

that grand old chair is my one regret.

Engraved thereon was a fine design,

but they took it away because it was mine.

A chair was here, but it’s here no more,

they took it from my prison door.

That chair was my great star of hope,

I had fixed it nice, with good “con” soap.

A big forty-five was carved there on,

the workmanship of a poor “ex-con.”

Who craves the beautiful sun to see,

to keep him from “eternity.”

From off the table they took my spoon,

believe me, gents, they were none too soon.

For if they had waited ‘till next day noon,

they never would have tried me on the ninth of June.

My luck was bad, so I hate to tell,

that I was about to bid you all farewell.

For all the Bulls were in their sleeves,

soon I’d have had them on their knees.

“Billy” the jailer was surprised no doubt,

to find something here that would let me out.

I tried quite hard to make it stick,

but "Bardsley Bill" was a little too quick.

Thorough sunshine and shadows of a beautiful day,

Mr. Cockney Hopkins would have made his getaway.

But "Bardsley Bill" come upon the scene,

saying "Hoppy, old boy, you cannot hit the green."

So here I am, and here I’ll stay,

maybe 'till judgment day.

But discouraged, "not," undaunted, "not at all,"

I still retain that stuff called "gall" (Mount Vernon Herald).