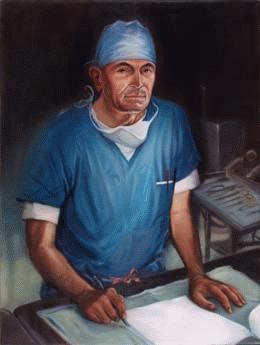

Pioneering heart surgeon Lester R. Sauvage’s first career goal was to become a Major League baseball player. His forceful mother insisted that he focus on his education instead. He entered medical school when he was just 17, graduated with honors at 21, served a stint in the Army, and completed two surgical residencies before settling in Seattle in 1959. In addition to a busy private practice (averaging more than 260 operations a year for 32 years), he also carried on important clinical research. With his colleagues at his initially small laboratory (now the Hope Heart Institute), he made major contributions to the development of coronary bypass surgery and artificial replacements for diseased arteries and valves. He also managed to realize his childhood dream of playing in the big leagues, after a fashion, by throwing out the opening ball at a 1995 Mariners’ game (where his pitch was clocked at a respectable 58 miles per hour). The Seattle-King County Association of Realtors recognized Sauvage’s many achievements in the field of medicine by naming him First Citizen of 1992.

Wapato Roots

Lester R. Sauvage was born in Wapato, located in Central Washington near Yakima, on November 15, 1926. His father, Lester Sauvage, was a sportsman who owned a men-only poolroom and bar called Jack’s Place. The two often went fishing together. The younger Sauvage once speculated that some of his skill as a surgeon was grounded in the many hours he spent cleaning fish with his father.

Neither his father nor his mother, Louise Brouillard, had been educated beyond elementary school, but they pushed Sauvage and his older sister, Coco, to excel academically. The family moved to Spokane in 1942 because his mother, a devout Catholic, thought the children could get a better education in the Catholic schools there. Sauvage enrolled as a junior in Gonzaga High School. Discipline was "strict, forceful, and timely." He remembered one of the school officials calling the new students together and telling them: "If any of you guys get out of line, we'll beat the hell out of you" (Sauvage, 8).

Sauvage’s mother had been a young widow when she met his father. Her first husband, a Yakima physician, had committed suicide a few years after their marriage. His old medical books, kept in a glass-fronted bookcase in the home where Sauvage grew up, piqued the young boy’s initial interest in medicine. He began browsing through them when he was in the fifth grade. "I often felt as if I were looking at things I wasn't supposed to see," he wrote. "But I was fascinated by those books and kept being drawn to them" (Sauvage, 4).

Still, as a junior in high school, he was more interested in baseball than medicine. "I had good control, a sneaky fastball, a fair curveball, and a forkball that had some action," he says, and dreamed of playing in the big leagues (Sauvage, 8). He had been designated starting pitcher for his high school team when his strong-willed mother told him that he was going to skip his senior year and enroll in the Jesuit-run Gonzaga University instead.

Strongly influenced by his mother’s Catholicism, Sauvage briefly considered becoming a Jesuit priest. He chose medicine over the priesthood "because of an underlying conviction that I could do God's work best as a doctor" (Open Heart, 11). His deep Christian faith remained an important part of his life, however. As a surgeon, he often spoke to his patients about spiritual issues, and took pride in ministering to their inner lives as much as to their physical problems. "People who are afflicted with these problems are brought into a close glimpse, if you will, with eternity," he told an interviewer in 1981. "If I can give a little guidance to people to enlarge their horizon or what they see, then I think I've done something that's every bit as important as putting a stitch in some artery someplace or another" (The Seattle Times, 1981).

Birth of a Surgeon

Sauvage enrolled in an accelerated pre-med program at Gonzaga in 1943, in the middle of World War II, at a time when medical schools were scrambling for students. There he developed the work habits that would govern much of the rest of his life: out of bed by 6 a.m., daily mass at 6:30 a.m., then off to classes, then studying until 2 a.m. He kept the same hours throughout his long career as a physician and clinical researcher, typically getting by with only three or four hours of sleep a night. The pattern was "beyond workaholism," his medical editor would say later. "It’s a new dimension he alone inhabits" (The Weekly, March 18, 1981).

He entered medical school at St. Louis University in Missouri in 1944. It was an exciting time in medicine, on the eve of the era of open-heart surgery. Within a decade, a heart-lung machine would be developed, making it possible for the human heart to be stopped, repaired, and restarted. Meanwhile, advances in X-ray diagnostic techniques, anesthetics, and pharmacology were paving the way for a new specialty in medicine: cardiovascular surgery. By his senior year in medical school, Sauvage had decided to specialize in that field.

He completed a one-year internship at the King County Hospital (now Harborview Medical Center) in Seattle in 1949 and immediately began a residency in vascular surgery at the University of Washington. His residency was interrupted when he was drafted into the Army Medical Corps in 1952, during the Korean War. He was given the rank of lieutenant and assigned to the Division of Experimental Surgery in the Army Medical Service Graduate School at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington D.C.

At Walter Reed, Sauvage became involved in research to find better ways to repair blood vessels that had been damaged by rifle fire or other war-related injuries. He conducted a series of experiments involving the insertion of blood vessel grafts in the aorta (the primary artery) in the chest of young pigs. When the pigs were slaughtered, six to eight months later, he examined the grafts. The work led to his first major research paper, "The Healing and Fate of Arterial Grafts," published in 1955.

Sauvage was discharged as a captain from the Army and returned to Seattle in 1955 to complete his residency in adult general and vascular surgery. Once painfully shy, he had become bold enough to make an overture to a young woman whose photograph he had seen in the window of a photo shop. Her name was Mary Ann Marti. She was a nursing student at Seattle University. He got her phone number and called her up: "Miss Marti, if you are not married, engaged or otherwise spoken for, I would greatly appreciate meeting you" (Sauvage, 17). They were married on June 9, 1956. Later that month, the young couple left for Boston, where Sauvage began a second residency, in pediatric and cardiovascular surgery, at the Children’s Medical Center.

Sauvage says that he had been promised a job developing and directing an open-heart surgery program at Children’s Hospital in Seattle when he completed his residency. However, when he returned to Seattle in December 1958 -- with Mary Ann and Lester Jr., the first of the couple's eight children -- he was told he would be merely an assistant, not the director of the program. He refused the altered position and, after two anchorless months, joined the practice of Dr. Alexander Bill, a cardiovascular surgeon at Providence Hospital in Seattle.

Pioneering Research

While establishing himself as a surgeon, Sauvage also continued the vascular research he had begun during his military service. Sister Genevieve (1887-1963), newly appointed administrator of what was then the Catholic-run Providence Hospital (now part of the secular Swedish Medical Center), offered him the use of a small white house behind the hospital. This was the modest beginning of the Reconstructive Cardiovascular Research Laboratory, precursor to the Hope Heart Institute.

The laboratory was supported almost exclusively by private grants. Sauvage would later attribute much of his success to the fact that his research was done outside a university or governmental setting, with private rather than public support. "Our secret of success," he said, "is a lack of bureaucracy" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1992).

In 1962, Sauvage became the first surgeon to successfully use a vein as a substitute for a coronary artery, in a series of experiments on dogs. His work, published the next year, was an important milestone in the development of coronary bypass surgery for humans. However, it initially met with skepticism. Many of his peers believed that veins (which have thinner walls than arteries) were not strong enough to handle the pressure of arterial blood. In a video interview recorded in 2004, Sauvage recalled an encounter with "a very distinguished individual in the field of cardiology," who told him that coronary bypass was "a surgical stunt of no practical significance." Today heart bypass operations are among the most common surgical procedures of any kind in the United States; more than half a million are performed every year.

The first such surgeries on humans were unsuccessful, but by 1967, a team at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio was reporting consistent and positive results. Their procedure involved using a segment of the saphenous vein (a long, straight vein in the leg) to create a detour around a cardiac artery blocked by arteriosclerosis (deposits of plaque) -- a method Sauvage had suggested in 1963. What became known as Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) creates a new route for blood to flow around blocked vessels, thereby restoring blood supply to the heart. Sauvage performed his first human coronary bypass in May 1968, followed by two more in the next few weeks. He soon became one of the Northwest’s leading specialists in the procedure.

Later, Sauvage contributed to an important modification of the procedure, substituting internal mammary arteries (soda-straw-sized vessels that run parallel to the breast bone, one on each side) for the saphenous vein. Mammary arteries are harder to use than veins from the leg, but they are more likely to stay open. Today more than 90 percent of all bypass patients receive at least one mammary graft.

Sauvage and his team at the Reconstructive Cardiovascular Research Laboratory also made a number of advances in the design of artificial arteries, using Dacron; and the repair of leaky heart valves, using tissue from the pericardium (the sac around the heart). Sauvage discovered that the porosity and fuzziness of blood vessel grafts made from Dacron allowed endothelial cells (those lining the heart and blood vessels) to grow around the graft, just as they do around living tissue. Royalties from the Dacron-based "Sauvage graft," patented in 1971, helped support further research at the laboratory for several decades.

"Saint Sauvage"

By the 1970s, Sauvage was one of Seattle’s busiest and best-known surgeons. In addition to his private practice at Providence Hospital, he had become chief of cardiac surgery at Children’s Hospital. He was legendary for his stamina, working 20 hours a day for six and sometimes seven days a week. He was also known for his extraordinary attentiveness to patients. He visited them at all hours in the hospital and willingly provided personal services, from washing their hair to spoon-feeding them. On at least one occasion, he sent his assistants off to rest while he cleaned the operating room himself. Some nurses and not a few of his patients called him "Saint Sauvage."

He also remained deeply involved with clinical research, and campaigned tirelessly for funds to support his laboratory (renamed the Reconstructive Cardiovascular Research Center in 1974). He was unabashed in using his patients as a "donor base" for the center, often sending them home from the hospital with a letter soliciting donations. Some of his fellow physicians criticized him for what they saw as his emotional manipulation of patients. Sauvage was unapologetic. His goal, he said, was to help patients find new directions for their lives. "To refuse to see surgery as a chance to redefine the goals of life is to approach it as a trade," he said. "It is not a trade. My patients have an eternal destiny. I must help them see what lies beyond the physical arrangement of an operation" (The Weekly, March 18, 1981). It seemed natural to him that patients would decide to redirect their lives toward supporting his research programs.

Sauvage’s high profile often made him a target for criticism. He was accused of grandstanding, of duplicating facilities and programs that were already in existence, and of relying on the appeal of religion and show business rather than scientific merit in his fund raising. His defenders attributed much of the nay-saying to professional jealousy. Many of his critics, they pointed out, were competing for the same patients and research dollars he was. "Of course Dr. Sauvage has a strong ego," said Joyce Renfrow, his scrub technician. "You need that to rip peoples’ chests open, hold their hearts in your hands, and survive day after day. But his mind is on serving other people, not on promoting himself" (The Weekly March 18, 1981).

Dreams and Hope

In 1980, Sauvage announced plans for a major expansion of the center. His goal was to bring together an international team of surgeons, hematologists, biochemists, and immunologists who could develop better ways of treating coronary disease and eventually help prevent the disease altogether. He assembled an international, celebrity-studded board of governors; convinced famed comedian Bob Hope to lend his name to the cause; and hired a public relations firm to coordinate a fund drive. He hoped to raise $8 million for what had become the Bob Hope International Heart Research Institute, and an additional $22 million for an endowment that could allow the institute to operate without government grants.

Grateful patients and their families kicked off the campaign with contributions of more than $200,000 and an anonymous donor added $1 million. Aided by generous publicity in the local press, the campaign raised almost $6 million by 1983 -- a sizeable sum, but far short of the $30 million goal. Plans for groundbreaking for a new building were postponed several times and finally cancelled.

The association with Bob Hope proved to be a mixed blessing. Some potential donors assumed that the wealthy entertainer was financing the institute and thus it was not in need of further support. Hope made one generous donation, of $100,000, but nothing more. The affiliation was quietly ended, by mutual agreement, in late 1987. The organization was renamed the Hope Heart Institute, retaining the name "Hope" for its symbolic value.

Sauvage retired from clinical surgery in 1991, after more than 32 years of nonstop practice, but he remained active in research and writing. In the next 15 years he wrote three books for lay people: The Open Heart, You Can Beat Heart Disease, and The Better Life Diet, all published in Seattle by the Better Life Press. His body of work also included a monograph on heart valve replacement, chapters in several medical textbooks, and more than 250 scientific papers. He received numerous awards over the years, including a Brotherhood Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews; the Jefferson Award, co-sponsored by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and the American Institute for Public Service; and the Washington State Medal of Merit.

His primary emphasis at the end of his career was on the prevention of heart disease. "We’re not going to defeat heart disease with a knife," he commented in a 2004 video interview. "Prevention is where we should be, more than having more sharp knives and more operating rooms and more talented surgeons."

Dr. Lester Sauvage died on June 5, 2015, at the age of 88.