On March 16, 1910, Ezra Meeker (1830-1928) departs from The Dalles, Oregon, to retrace for a second time the old overland emigrant trail to Oregon. Meeker, an early Puyallup pioneer and successful hops merchant, first traversed the emigrant trail to Oregon with his wife Eliza Jane (1834-1909) and their infant son Marion in 1852. He plans to map the Oregon Trail, to encourage federal funding for permanent trail preservation, and promote construction of a transcontinental national highway for automobile traffic.

First Return Trip

From 1906 to 1908, Meeker and a driver, William Mardon, made a highly publicized round-trip journey across the Oregon Trail west to east in a covered wagon pulled by oxen. Meeker placed markers at significant points on the trail and promoted trail preservation. After reaching the end (or, from the pioneer perspective, the beginning) of the trail in Omaha, Nebraska, he continued east. (The official beginning of the Oregon Trail, according to the National Trail System Act of 2004, is Independence, Missouri, but Meeker's retracing diverged from the trail at Omaha. Many pioneers picked up the trail at the point closest to the homes they were leaving.)

Meeker ultimately took the wagon over the Brooklyn Bridge and into Manhattan through throngs of New Yorkers and then on to Washington, D.C. where he parked the rig in front of the White House and met with President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919). At Meeker's urging in 1908, Congress considered House Bill 11722 earmarking $50,000 for marking the Oregon Trail. Although the bill failed, Meeker was sufficiently encouraged to begin planning for a second trip.

The Wheels Of Time

After returning to Puget Sound in July 1908, Meeker ran a restaurant. In the summer and fall of 1909 he displayed his ox-team and wagon and other Oregon Trail memorabilia at Seattle's Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. He also published an autobiography, Ventures and Adventures. He then turned his attention to preparing for a second west-to-east journey across the Oregon Trail.

Meeker's 1906-1908 trip had shown him that although some areas of the emigrant road were still clearly marked with deep wagon ruts made by hundreds of thousands of wagon wheels, the passage of time had obscured many other portions.

The old emigrant trail to the Oregon country and after 1848, to Oregon Territory, now known largely because of Ezra Meeker's tireless promotion as the Oregon Trail, fell into disuse after the completion of the Central and Union Pacific Railroad's first transcontinental line on May 10, 1869. After that time, only emigrants who could not scrape together funds to purchase train tickets undertook the arduous five-month journey overland. In the 40 intervening years, weather, plowing, the spread of farms and towns, and the creation of roads and railroads near and on the path had made it unrecognizable in many places. Meeker recounted his frustration trying to follow the trail's exact path during his 1906-1908 trip in Story of the Lost Trail To Oregon, originally published in 1915 and reprinted in 1998:

"We could find traces of it here and there, and then lose it. Part had been fenced up, the fields plowed, and all visible signs gone. In other places nature had been at work. The storms of half a century have changed the face of the country, the river crossings and other landmarks, by growth and vegetation and otherwise. Then again, cities have been built over it, great irrigation ditches have been dug, and so it became evident that it would be impossible to recover the whole of the old track without more ample means" (p. 28).

The chief purpose of Meeker's second trip was to locate and mark parts of the trail he had failed to identify on his first trip.

Preparing To Map The Trail

Using government land surveys made when township lines were being drawn in Idaho, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas, advice from other older settlers and Indians, and his own powers of observation, Meeker tried to pinpoint the location of the historic trail.

While Meeker was in California doing research to prepare for the journey, he received word that Eliza, his wife of 58 years, had died on October 15, 1909, in the Sound View Sanitarium in Seattle. Eliza, whose planning and culinary skills Meeker always gave credit for the success of their 1852 journey across the trail, had been an invalid for some years prior to her death and had lived from at least 1906 mainly at the Seattle home of their daughter Carrie Meeker Osborne. Meeker returned to Seattle by train to lay his wife of 58 years to rest in Puyallup's Woodbine Cemetery.

Returning to California, Meeker drove his wagon in the Rose Bowl Parade in Pasadena, California, a commitment he had made before Eliza's death. Highly accomplished in public relations, Meeker was well aware that his wiry frame and flowing white hair and beard as he perched in the ox-drawn wagon drew attention to the cause of trail preservation. He sought a place in the spotlight whenever possible.

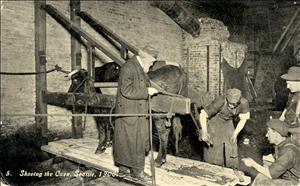

In early March 1910, he shipped the oxen Dave and Dandy to The Dalles for shoeing in preparation for the second journey. This second trip took two years and involved many meetings with local history experts along the way and much tracing and retracing of the general area in order to locate lost portions of the trail. Meeker described the engaging process of locating the trail in Ox Team Days or The Old Oregon Trail, written by Meeker in 1906 and revised and edited by Howard Droker in 1932:

"This search for the 'lost trail' grew more and more fascinating as the work progressed. Almost every day brought the joy of some new discovery. Once I remember finding the remnant of the historic highway running under two fences that lined a new road; the rest of the old pioneer trail had been wiped out by the grading and plowing of the farms. Again I discovered in an undisturbed sandy stretch where the trail by actual measurement was fully fifteen feet deep and seventy-five feet wide. Through the sage-covered lands I soon learned to recognize the old trail by its countenance, as one might say. The trampling of the sage and other rough vegetation had made it take on a slightly different color from the rest of the country; the hue was unmistakable when one learned to recognize it. Thus piece by piece the trail of the pioneers was found and charted" (p. 276).

Ezra's Perilous Adventures

Meeker's round-trip journey took two and a half years. On his way back west he branched off the Oregon Trail, camping in front of the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. Meeker was filmed rather self-consciously crossing the Loop Fork of the Platte River. He hoped to use the increasingly popular medium of cinema to publicize and honor the pioneer experience. Later, a flood in the Rocky Mountains almost washed Meeker and his rig away. His faithful trail dog, Jim, disappeared at a train station and was not returned despite Meeker's offer of a reward. He finally made it back to Puyallup on August 26, 1912.

Meeker counted this journey a success: the Oregon Trail was mapped. Summing up the trip in Ox Team Days, he wrote:

"All in all this was a more strenuous trip than the previous drive to the national capital, and from a historical point of view it was more prolific in results. At the end of the journey, during which I passed my eightieth birthday, I had plotted sixteen hundred miles of the historic highway. A map of it nearly forty feet long has been made with painstaking care" (p. 277).

Promoting the Trail By Car and By Plane

Although he was 80 years old, this second trip to promote the preservation of the Oregon Trail was by no means Ezra Meeker's swan song. In 1915 he drove across the trail in a Pathfinder Touring Car with his wagon cover mounted on the top. The vehicle was nicknamed the Schoonermobile, a nod to the Prairie Schooner wagon that was most commonly used on the Oregon Trail. Using this trip primarily to lecture on the need for and military value of a national highway, in 1916 Meeker met with President Woodrow Wilson, who endorsed the idea of a national highway.

In October 1924 Meeker once more brought publicity to the Oregon Trail by traveling portions of the route as an airplane passenger. Lt. Oakley G. Kelley was Meeker's pilot. He, along with Lt. John A. Macready, had set the first nonstop transcontinental flight record by flying nonstop without refueling from New York to San Diego on May 2-3, 1923. The airplane was the same one in which Kelley had set the record: a single-engine, high-wing Army Fokker T-2. By ox, Meeker sped along the trail at two miles per hour. His plane flew the route at 100 miles per hour.