On June 17, 1877, citizens of Colfax panic upon hearing news, which turns out to be a false rumor, of imminent Indian attack. The context is the start of the Nez Perce War, which broke out in Idaho on June 14, 1877. Reports of fighting and supposed Nez Perce atrocities reach Colfax on June 15. Two days later the unfounded rumor reaches the town, and panic ensues.

Context of the Nez Perce War

The Nez Perce, called Nimipu by themselves, lived on about 28,000 acres in western Idaho and Eastern Washington, rode the horse beginning in the 1700s, greeted Lewis and Clark in 1805, and were less affected by introduced diseases than were tribes farther west because of less contact with explorers and fur trappers. The mission of Henry and Eliza Spalding in 1836 made many converts, but Spalding's intolerance for traditional Nez Perce culture began a deep split in the tribe.

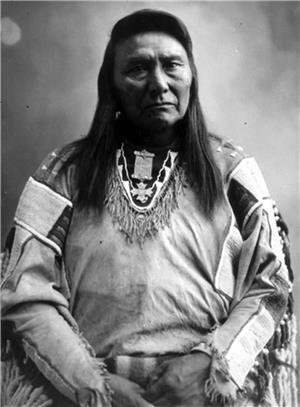

An 1855 treaty granted the Nez Perce a reservation including most of the original seven million acres of their homeland. In 1860 gold was discovered on the reservation and white miners swarmed onto it illegally. The supply town of Lewiston was built on Indian land. A new treaty in 1863 reduced Nez Perce land by 90 percent. It was signed by Christian Nez Perce and rejected by traditional leaders, the side known as non-Treaty Nez Perce. In June 1877 the U.S. Army was in the process of pressuring Chief Joseph to move his non-Treaty people to the reservation when on June 14, 1877, young Nez Perce warriors killed four settlers. This set off the war.

The Nez Perce war pitted the non-Treaty Nez Perce bands against a force of 2,000 U.S. Army soldiers, many citizen volunteers, and 10 different Indian tribes. On June 17, 1877, the White Bird Battle occurred in Idaho. In this battle the Nez Perce was a force to be reckoned with. The Clearwater Battle (July 11-12) was indecisive, but the Nez Perce were strengthened when the warrior Looking Glass joined. On August 9, the Big Hole Battle occurred in which some 90 Nez Perce lives were lost, many of them women and children. The final Bear Paw Battle lasted from September 3 to October 5, with great losses on both sides. At this point Chief Joseph negotiated an end to the fighting.

Back at Colfax

Word of the June 14, 1877, Nez Perce attacks on white settlers south and west of Grangeville, Idaho, about 90 miles southeast of Colfax, reached Colfax on June 15. No census or other population records are available for Colfax for 1877. The town had been platted in 1872 and historical accounts reflect that it had grown fairly slowly but steadily since that time. A reasonable estimate of Colfax’s population in June 1877 is 200 to 300, based on contemporary accounts and subsequent records. More Indians, from various tribes, than whites lived in the area at the time.

Considerable paranoia reigned in Colfax over the next few days. False rumors swept Whitman County that other tribes had joined the Nez Perce and were on the warpath. "Utterly unfounded rumors of massacres and depredations were passed from person to person ... reason seemed to have temporarily surrendered her citadel and wild fancy ruled," wrote W. H. Lever in his 1901 book, An Illustrated History of Whitman County, State of Washington.

At about 11 a.m. on Sunday morning, June 17, a camp meeting (a religious gathering; at that time Colfax had no church) was being held at Chase’s Mill, about 18 miles east of Colfax (near Palouse.) One Joe Evans galloped into the camp and told the congregation "The Indians are coming down Union Flat (south of Colfax), killing and burning everything in sight" (Sutherland).

In fact, the first actual battle of the war, the White Bird Battle, had taken place earlier that morning much farther southeast. In it the Nez Perce had defeated a band of United States Army soldiers and volunteers at White Bird Canyon in Idaho. But this had just occurred about two hours earlier nearly 100 miles away. Word of the battle had not yet reached Colfax.

Panic Attack

"The meeting broke up without waiting for the benediction, and everyone started for home or for Colfax," recalled pioneer George Washington Sutherland in a 1940 interview. Lever wrote a vivid account of what happened next. "The people rushed pell-mell for Colfax. Wagons were driven down the steep hills leading to the county seat [Colfax] at a gallop. Never before ... have the streets of Colfax witnessed such a scene of turmoil. Terror ruled supreme ... weapons of all kinds were gotten ready for use. Men rushed about excitedly, while women and children greeted each new report of butcheries with loud lamentations and wailings. The hostile band of Indians many miles away were no doubt totally unconscious of the commotion they were causing." This may be true as there are no Native American accounts of the great "Indian scare" in Colfax on June 17, 1877.

A group of volunteers (history does not record how many were in the group) was formed and went out to round up all the guns the men could find. Sutherland reported the volunteers rounded up 22 rifles, shotguns, and pistols. He stood duty that night on the hills at the south end of town where the Indians were expected to come through. The night passed without incident.

The next day, Sutherland was ordered to reconnoiter and report. He went to Three Forks (Pullman) and Palouse City (now Palouse), but saw no Indians there. Within a couple of days he was in Idaho. He traveled the west-central part of the state extensively over the next few months looking for trouble, but saw no fighting and few Indians.

Back in Whitman County, a 125–foot square blockhouse was quickly erected near Palouse City, and 200 people spent several days there during the height of the scare. Lever added wryly "Some of the male refugees [who remained] at Colfax mollified their own feelings and proved to their wives and families their animus to protect these helpless dependents by digging rifle-pits on the hillsides."

A number of people from Colfax and surrounding communities fled. Farms were deserted. Livestock were either left in their corrals without food or water, or wandered the range at will foraging what they could.

Many of those fleeing set out for Walla Walla, an established town with a large United States Army fort. Mary Ann Cashup, a settler from the Whitman County town of Cottonwood Springs (now Cashup) wrote a telling letter the following month as she fled to Walla Walla: "We are fleeing from the Indians. They have broke out and are killing settlers ... our horses, hogs and cattle are behind. The roads are full of people leaving their homes and everything behind. The men have gone back to fight."

Back to Reality

But despite the panic, some kept their heads. One persistent rumor held that Indians had crossed the Clearwater River (in western Idaho), were moving north and killing everyone in sight. On June 18 a group of about 10 men left Colfax to reconnoiter and get the facts. They went to the residence of one Mr. Howard near Mt. Idaho, Idaho. Howard had just completed a stockade; later in the summer of 1877 this would become a federal camp called Camp Howard.

The men from Colfax learned that the Indians had not crossed the Clearwater, but then they heard an even more disturbing rumor: an Indian from the Coeur d’Alene Mission (25 miles east of present-day Coeur d’Alene, Idaho) claimed his tribe was going to attack both Howard’s stockade and Colfax the next day.

D. S. Bowman and James Tipton of Colfax decided to travel to the Coeur d’Alene Mission to see if this were true. They arrived at the Native American camp, which was in the same village as the Coeur d’Alene Mission, on the afternoon of the 19th. "We found the red men in a terrible uproar," reported Bowman. "Some were on horseback and some on foot, but all were painted red."

Palouse and Spokane Reactions

Contrary to planning an attack, the Indians believed that it was the Americans who were preparing to attack them, and were rallying as a defensive measure. The Spokane and Palouse tribes were also expecting an attack and were preparing for war; indeed, a chief from the Palouse Tribe and another chief (Bowman simply referred to him as the "Snake River Chief") were also present at the Coeur d’Alene camp when Bowman and Tipton arrived. One wrong move by either side could have been the spark for a much wider conflict.

Bowman and Tipton held a conference with the three chiefs at the camp. "The Snake River Chief opened the council," recounted Bowman some years later. "He stood six feet in his moccasins. His black hair waved over his shoulders and his eyes flashed fire from under his heavy brows."

These chiefs told Bowman they did not want war. "We are satisfied," Bowman reported that the Snake River Chief said. "You gave us this land and you gave us wagons and plows and tools to build these houses, and we want to live together and be friends."

Bowman told the chiefs that the American’s war was with the Nez Perce Tribe, and that likewise the settlers did not want war with any other tribes.

End of the Panic

All of the chiefs provided Bowman and Tipton with certificates affirming their peaceful intentions. Coeur d'Alene Chief Seltice provided an escort to return Bowman and Tipton safely to Colfax. They arrived during the night of June 19-20 and broke the news promptly the following morning. This effectively ended the crisis in Colfax and people began returning to their homes, though tension would remain high throughout the summer as the Nez Perce war continued.

A few Indians ransacked homes vacated by panicked settlers, but others actively protected the homes from hostile acts and also protected the settlers’ wheat crops from damage caused by roaming cattle. Spokane Chief Garry reportedly rode around trying to put the whites at ease and Coeur d'Alene Chief Seltice along with his band was "especially active in thus manifesting their friendly, benevolent position" (Lever). Both these chiefs had rebuffed Nez Perce appeals to the Spokanes and Coeur d'Alenes to join the war.

The Nez Perce War ended on October 5, 1877.