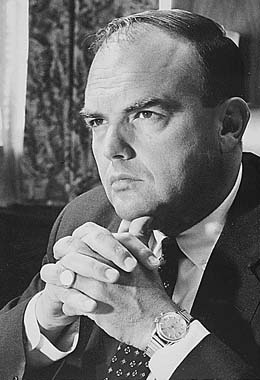

John D. Ehrlichman was a former Seattle land use lawyer who experienced both a meteoric rise and a dramatic fall from grace as a result of his loyalty to President Richard M. Nixon. He was rewarded for his work on Nixon's successful campaign for the presidency in 1968 by being named White House counsel and then chief of domestic policy. He pursued a relatively progressive agenda on domestic issues, promoting affirmative action, workers' rights, the sovereignty of Native American tribes, and clean air and water legislation. He was instrumental in the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. All these accomplishments were overshadowed by his role in the political scandal known as Watergate. In January 1973 -- just one month after the Seattle-King County Association of Realtors honored Ehrlichman as its First Citizen for 1972 -- seven men went on trial in connection with a burglary at the Watergate hotel and office complex in Washington, D.C. The trial was the first in a series of events that would force Nixon to resign and send many of his aides, including Ehrlichman, to prison.

Overshadowed by Scandal

As a young attorney in Seattle in the 1950s and 1960s, Ehrlichman was widely admired for his expertise on urban land use and zoning. He was best known for filing a successful lawsuit to prevent construction of an aluminum plant on tiny Guemes Island near Anacortes in 1967. He was active in the Municipal League, supporting its efforts to clean up Lake Washington and improve the civic infrastructure of Seattle and King County. Seattle lawyer and civic leader James R. Ellis (b. 1921) was among those who praised his appointment to high-level jobs in the Nixon White House. Describing him as "one of the ablest lawyers in this state," Ellis said "I would expect him to be orderly and darned effective in whatever he put his talents to work at" (The Seattle Times, 1968).

Much later, after the Watergate scandal reached full flood, Ellis says he asked Ehrlichman why he didn't steer Nixon away from the criminal acts that led to the collapse of his administration. "I asked him, 'Why didn't you say, No, Mr. President, you can't do that -- it's illegal?' He said, 'When you're working for the President of the United States and he asks you to do something, you don't say, wait a minute while I consult my lawyer'" (Ellis interview).

Often brusque and pugnacious in his public demeanor, Ehrlichman symbolized what one writer called "the administration's determination to confront its foes and reshape policy over a wide front" (Washington Post). He eventually became deeply enmeshed in efforts to cover up various abuses of power by the administration, ranging from burglary to bribery. He would later tell a U.S. District Court judge that he had developed "an exaggerated sense of my obligation to do as I was bidden" (Washington Post).

In separate trials in 1974 and 1975, Ehrlichman was convicted of conspiracy, obstruction of justice, and perjury in connection with politically motivated burglaries at Watergate and in the office of a psychiatrist in California. He was sentenced to up to eight years in prison, of which he served 18 months. He made a new life for himself as a writer and consultant after his release in 1978. However, Watergate became the defining moment of his life. Whatever else he did, wherever he went, he was invariably identified as the disgraced White House aide who was jailed because of Watergate.

Author Theodore H. White once offered another view. "His shop was one of the few at the [Nixon] White House where ideas were seriously entertained -- good ideas, too, on energy, on land-use policy, on urbanization, on preservation of the American environment," he wrote in The Making of the President 1972. Jim Ellis agrees. "John was pushing Nixon in a positive direction, in a lot of ways that have been forgotten," he says. "I just wish he could have been stronger" (Ellis interview).

California Days

John Daniel Ehrlichman was born on March 20, 1925, in Tacoma, the only child of Rudolph Irwin and Lillian C. Ehrlichman. His father was a banker and financier who had grown up in a tight-knit family in Tacoma and Seattle. Rudolph Ehrlichman (1897-1942) was particularly close to his older brother, Ben B. Ehrlichman (1895-1971). Both brothers served in the Army Signal Corps' Air Service during World War I. After the war, they worked together in the investment-banking firm of Drumheller, Ehrlichman and White. Rudolph left the firm in 1931 and moved to Los Angeles with his wife and young son. Ben remained in Seattle, where he became a leading figure in business and civic circles and, eventually, a mentor to his nephew John.

John Ehrlichman developed an early interest in the outdoors, often camping and fishing in the High Sierra Mountains near Los Angeles. He was an active Boy Scout and an avid fly fisherman. He attained the rank of Eagle Scout -- the highest ranking in scouting -- in 1942. (In 1970, he would receive the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award, given to "Eagle Scouts who have distinguished themselves in business, professions, and service to their country.") For several summers, he worked as an assistant to the director of the Boy Scouts' Camp Wolverton in Sequoia National Park. He is credited with helping develop Wolverton and neighboring Camp Josepho, both still used by Boy Scouts, their families, and community groups in southern California.

Ehrlichman was barely 17 and in his last weeks of high school when his father was killed in a plane crash in Canada. Rudolph Ehrlichman had joined the Royal Canadian Air Force as a flight instructor in 1940, a year after the outbreak of World War II but a year before the United States entered the war. He was a passenger in a patrol plane that was being flown from St. Johns, Newfoundland, to Nova Scotia for maintenance. The plane crashed shortly after take-off on May 6, 1942, killing all eight people on board.

GI John

John Ehrlichman completed his freshman year at the University of California at Los Angeles in 1943 and then enlisted in the Army Air Forces. He flew 26 missions over Germany as a navigator in a B-24 bomber in the Eighth Air Force, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and other decorations.

After the war, he returned to UCLA with financial help from the "GI Bill" (the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, which provided educational benefits for returning veterans). One of his fellow classmates was his future wife and the mother of five of his six children, Jeanne. Another was H. R. Haldeman (1926-1993), who would bring Ehrlichman into Nixon's inner circle.

Ehrlichman graduated from UCLA in 1948 and went on to Stanford University Law School. He married Jeanne in 1950. A talented pianist, Jeanne Ehrlichman taught elementary school for several years. Later, after couple moved to Seattle, she became the education director for the Seattle Symphony.

After graduating from law school in 1951, Ehrlichman worked briefly for a Los Angeles law firm. His uncle Ben encouraged him to establish his own firm in Seattle. Ben Ehrlichman, president of the Municipal League at the time, introduced John to other civic-minded people in Seattle, including Jim Ellis. "I told him about the opportunities I saw for legal work in the area," Ellis recalls. "I told him there was quite a demand for lawyers in land use" (Ellis interview).

Presidential Politics

In 1960, Ehrlichman's college friend (and fellow Eagle Scout) H. R. Haldeman -- by then an advertising executive in Los Angeles -- recruited him to work on Nixon's first presidential campaign, against John F. Kennedy. Haldeman and Ehrlichman teamed up again two years later, as manager and scheduler, respectively, on Nixon's failed campaign to become governor of California. When Nixon ran again for the presidency, in 1968, Haldeman served as the campaign manager and Ehrlichman as tour director and convention organizer. This time, they offered the electorate a "new" Nixon, one who appeared relaxed, calm, and in control. Nixon, who had narrowly lost the 1960 election, narrowly won in 1968.

Ehrlichman and Haldeman continued their close association once Nixon took office and they moved into top positions in the White House. Columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak once described them in this way: "On the surface, they look like Tweedledee and Tweedledum: Schoolmates at UCLA, brusque, high on Germanic efficiency, low on frivolity, new to government and Washington ..." (The Seattle Times, 1969). Detractors referred to them as "the Berlin wall" because "they were said to shield the reclusive, occasionally paranoid President from unpleasant news and unpalatable choices" (New York Times, 1999).

As the 1972 presidential election approached, Nixon and his top aides became obsessed with stopping "leaks" of information damaging to the administration. One of their first targets was Daniel J. Ellsberg, a former National Security Council aide who had given reporters copies of a secret Pentagon study of American involvement in the Vietnam War. On Nixon's orders, Ehrlichman created a covert group -- the White House Special Investigations Unit, more commonly known as "the plumbers" -- to stop such leaks and investigate other "sensitive security matters." Ehrlichman put his chief deputy, Egil Krogh Jr. (a former associate in Ehrlichman's law firm), in charge of the unit.

In September 1971, Krogh organized a break-in at the Beverly Hills office of Dr. Lewis J. Fielding, a psychiatrist who had treated Daniel Ellsberg. The goal was to find material in Ellsberg's case file that could be used to discredit and "neutralize" him. Ehrlichman later described this burglary as "the seminal Watergate episode," one that set the tone for everything that followed (New York Times, 1999). The break-in became public in June 1973, when prosecutors discovered a memo from Krogh to Ehrlichman detailing plans for the burglary. The news would help fuel the burgeoning Watergate scandal, and add to Ehrlichman's personal legal problems.

Watergate

In the early morning hours of June 17, 1972, burglars working for the Committee to Re-elect the President broke into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex. Their objective was to replace a faulty telephone wiretap installed during an earlier break-in. This time, the burglars were discovered and arrested, in what would prove to be the catalyst for a national political trauma.

On June 19, the Washington Post reported that one of the burglars -- James W. McCord Jr., a former Central Intelligence Agent -- was the "security coordinator" for the Committee for the Re-Election of the President. That same day, in a conversation recorded by a secret taping system in the Oval Office, Ehrlichman warned Nixon that "disloyal guys" in the Justice Department would be investigating the break-in. He predicted they would "second-guess any story that you come up with," and for that reason, "whatever we come up with has got to be water-tight" (New York Times, 1997).

Despite the warning, Nixon did not initially think that much fuss would be made over a Republican committee trying to bug the Democratic headquarters. In another secretly recorded conversation, on November 1, he told Ehrlichman that the burglary was "so dumb" that "tying it to us is an insult to our intelligence." Ehrlichman agreed. "We don't mind being called crooks, but not stupid crooks," he said, laughing (New York Times).

Nixon was re-elected in a historic landslide on November 7, 1972, defeating his Democratic challenger, George McGovern, by more than 20 percentage points and taking every electoral vote except those of Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Meanwhile, prosecutors brought charges against the five burglars and two other men who were accused of planning the burglary.

In December, the Seattle-King County Association of Realtors proudly selected John Ehrlichman -- the local boy who had made good -- as its First Citizen for 1972. However, by the time Ehrlichman received the award, at a banquet in Seattle on March 2, 1973, it was clear that Watergate was a problem that was not going to go away.

Containment Policy

As the Watergate drama continued to unfold, Ehrlichman emerged as a key architect of a containment policy designed to mitigate the political damage to the administration. He advised Nixon to deflect attention from the scandal by sacrificing L. Patrick Gray III, who was undergoing confirmation hearings to become director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Gray was being sharply questioned over his relationship with the White House, and prospects for his approval looked dim. In a remark that became part of the political lexicon of Watergate, Ehrlichman suggested that Gray be left "twisting slowly, slowly in the wind."

In March 1973, James McCord, one of the original seven Watergate defendants, told Judge John Sirica that the defendants had been bribed and pressured into silence and perjury by people associated with the President. Ehrlichman coined another memorable phrase by recommending that Nixon respond with a "modified limited hang out." In other words: the White House would investigate itself, let a small part of the truth "hang out," and release the report to the press -- hoping that would put the entire matter to rest.

Still, the pressure continued to mount. In televised hearings conducted by a special Senate committee, John W. Dean III -- who had replaced Ehrlichman as White House counsel -- implicated the President and his two top advisors in the effort to cover-up the administration's involvement in the Watergate break-in and other illegal activities. Nixon called Ehrlichman and Haldeman to the presidential retreat at Camp David and told them they would have to resign. He announced their resignations in a televised address on April 30. Even that did not staunch the scandal. Facing impeachment and almost certain removal from office, Nixon himself resigned on August 9, 1974.

Ehrlichman briefly returned to his home in Hunts Point, near Bellevue, after being forced to leave his job in the White House. He continued to defend Nixon, at least publicly, telling local newspaper and television reporters that he was certain the administration would rebound. He remained combative and unapologetic after he was indicted by a grand jury in Los Angeles in connection with the burglary in the office of Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist, and by another grand jury in Washington, D.C., for his role in the Watergate cover-up. Privately, he asked Nixon for a presidential pardon, without success.

On January 1, 1975, Ehrlichman was found guilty of conspiracy, obstruction of justice, and two counts of making false statements to a grand jury in the Watergate case. He was convicted earlier of conspiracy to violate civil rights and three counts of making a false statement to a grand jury in the Ellsberg case. He was sentenced to two and a half to eight years in prison, the sentences to run concurrently.

He was one of 25 members of the Nixon administration who were convicted of crimes they committed during his presidency.

Aftermath

While his convictions were being appealed, Ehrlichman moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, leaving behind his wife of 25 years, Jeanne, and their five children. He grew a beard and began working on a fictionalized account of his experiences in Washington. The novel, titled The Company, was published by Simon and Schuster in June 1976. It sold more than a million copies and was the basis for the 1977 television mini-series Washington: Behind Closed Doors.

Meanwhile, Ehrlichman decided to abandon the appeals. On October 28, 1976, he entered a minimum-security federal prison at Safford, Arizona, to begin serving his sentence. He was paroled 18 months later. His divorce was finalized six months after his release.

Ehrlichman returned to New Mexico, where he continued the process of reinventing himself. He married for a second time and had a sixth child, a son, named Michael, born on October 27, 1980. He nurtured the artistic bent that had surfaced during his White House years, when he often amused himself by making sketches on White House stationery. He sold some of his drawings of Nixon and several Cabinet members at an auction, and had at least one gallery exhibit. Once known for his combativeness and discipline, he was relaxed and amiable in interviews with reporters who sought him out for occasional updates on Watergate figures.

He continued to write, producing two other novels and a memoir, Witness to Power: The Nixon Years, published in 1982. New York Times book reviewer Christopher Lehman-Haupt described the memoir as "accusatory, funny, revelatory, apologetic, vindictive, analytic and mournful." Its very disorderliness, he added, "serves to heighten one's sense of the author's strength of feeling -- his anger, hurt and bewilderment at being caught in the machinery that eventually destroyed him" (New York times, 1982). Commentator Daniel Schorr, discussing the number of books published by Ehrlichman and many of his White House colleagues, including Nixon, once remarked that "the wages of sin include royalties" (National Public Radio, March 18, 1998).

In 1986, the New York Times described Ehrlichman as looking "a bit like a leftist academic," with a beard and a "relaxed dressing style." He seemed at ease with himself. "I prefer this life -- where you quit at 1:30 in the afternoon," he told the paper. He declined to comment on his earnings, but he did say: "Financially, things are much better than when we were in Washington."

Ehrlichman's second marriage, to Christine Peacock McLaurine, ended in divorce. He again remarried and, in 1991, moved to Atlanta, where he worked as a consultant for an engineering company involved in the disposal of hazardous waste. He died at his home there on February 14, 1999, at age 73, from complications of diabetes. Survivors included his third wife, Karen; three sons and two daughters from his first marriage (Peter of Seattle; Tom of Everett; Rob of San Francisco; and Jan Ehrlichman and Jody Pineda of Santa Fe); a son from his second marriage (Michael of Princeton, New Jersey), and his 97-year-old mother, Lillian, of Los Angeles.

Shortly before he was paroled from prison, Ehrlichman sent a taped statement to the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. "I went and lied," he said, "and I'm paying the price for that lack of willpower. I abdicated my moral judgments and turned them over to somebody else. And if I had any advice for my kids, it would be never -- to never, ever defer your moral judgments to anybody" (Washington Post).

According to his son Tom, an Everett lawyer, Ehrlichman often expressed remorse for the impact of his wrongdoing on his family, along with the hope that history would remember the accomplishments as well as the crimes of the Nixon administration (New York Times, 1999).