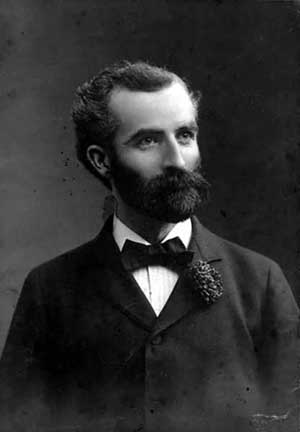

Edmond Meany was one of the University of Washington's most notable history professors. His passion for state history helped promote the region at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Expostion. A true renaissance man, Meany was also a journalist, a botanist, a State Representative, a playwright and -- in his later years -- a mountain climber. He was well-loved by his students, and a lecture hall, hotel, ski lodge, mountain peak, and mountain crest have been named in his honor.

Early Years

Edmond Stephen Meany was born on December 28, 1862, in East Saginaw, Michigan. When he was 14, he moved west with his parents Stephen and Margaret, and his 13-year-old sister, Mary. They arrived in Seattle in 1877, then a frontier town of about 3,000 residents. The Meanys moved into a small home on 3rd Avenue between Pike and Pine streets, nor far from Arthur Denny, Seattle’s founding father.

The following year, Meany enrolled in the Territorial University, located a few blocks away, and began preparatory studies for college. Even though the school was poorly funded -- it had already been closed twice since it opened in 1861 -- he became enamored with the institution to which he would be associated with for most of his life. He also developed long-lasting friendships with some of his classmates, including J. E. Chilberg (1867-1954), who would later head the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Ward, whom Meany would later marry.

In 1880, Meany's father was killed in a boating accident on the Skagit River while he was mining gold in the Cascade Mountains. Now in charge of the household. Edmond abandoned his studies. The family moved to California to stay with relatives, but returned to Seattle a year later. Meany worked at various small jobs, including sweeping the floors at Dexter Horton’s bank. He was concerned that he wouldn’t be able to afford college costs, but then an anonymous benefactor paid his tuition. Years later Meany found out that it was Horton who had made the payment.

Meany pursued a Bachelor of Science degree and developed a keen interest in botany. He funded his continued education by working for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as supervisor of carriers and collections. He also distributed the Portland Oregonian. Despite his long hours at work, he graduated as valedictorian of his class in 1885.

Paper Trail

Once out of college, Meany stayed on with the Post-Intelligencer and eventually became night editor. He enjoyed writing news items and editorials and had hopes of publishing his own newspaper. He got his chance in 1888, when he and Alexander Begg began publication of the Seattle Trade Journal, and the literary periodical, Puget Sound Magazine. Both were failures. Meany briefly operated a greenhouse after that, but returned to journalism.

In 1889, soon after he married Lizzie Ward, Meany became treasurer of the Seattle Press, which had just begun publication. In an effort to promote the paper, the publishers sponsored an expedition to traverse the Olympic Mountains, a feat which had never been accomplished and documented. The expedition was led by James H. Christie, and Meany offered the use of his greenhouse as headquarters.

The trek took most of the winter, and in the spring the Press received a telegram from Aberdeen stating that the men had made it safely through. Upon their return, the paper published their full story, along with photos, maps, and a complete roster of peaks, which they named. Among them was Mount Meany, a tall, thin mountain with red rocks on top, which reminded the hikers of their red-headed friend back in Seattle.

Fair Representation

In 1890, Meany became press agent for the Washington World’s Fair Association, which was promoting the state’s participation in the upcoming Columbian Exposition, to be held in Chicago in 1893. He handled the task with such aplomb that King County Republicans nominated him to run for the state House of Representatives for the 42nd district. He won and served for two terms.

His roles as promoter and State Representative allowed him to tour throughout Washington, and this broadened his interest in the state and its history. While in office, he proposed legislation to set aside land for a new campus for the University of Washington, which had outgrown its 10-acre tract in downtown Seattle. The measure passed with wide support, as did his proposal for increased funding for the University.

Meanwhile, problems arose within the Fair Association. On May 20, 1891, Ezra Meeker was elected Executive Commissioner, and although Meany initially praised him, Meeker started picking fights with Meany and the rest of the committee almost immediately. He complained that he been denied access for exhibit funding, and went so far as to publicly (and falsely) accuse Meany of financial impropriety. Meeker was removed from the position on August 21, 1891, yet he continued to snipe at Meany in the papers until 1893, when he backed down and apologized with little or no explanation.

In the end, Washington’s participation in the Columbian Exposition was a success. Meany spent much of 1893 in Chicago with his wife and newborn son, Thomas. Besides staffing the desk in the front gallery of the Washington State Building, Meany sent out a large number of publicity releases and magazine articles during the duration of the fair, extolling Washington’s resources and progress. He would later draw from his accomplishments at the fair and apply them to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in 1909.

Back to School

The Meanys returned home at the end of 1893 rich in experience but poor in the bankbook. Meany’s pay as a press agent was minimal, and his expenses outweighed his income. But by spring, he was hired as secretary to the University of Washington Board of Regents, just in time to welcome his newborn daughter, Margaret. He chose not to run for a third term as State Representative, and became the University’s chief lobbyist in Olympia. A year later he was hired full-time as University registrar.

By this time, all of his work with the state and the university had kindled a deep, almost insatiable, interest in local history. Meany began collecting and reading as many historical documents and books that he could get his hands on. He began teaching in 1896, and was in charge of two lecture courses, History and Forestry. He soon became a professor, and after attending summer studies at the University of Wisconsin, he earned a master of letters degree in 1901.

Although his teaching sometimes lapsed into sentimentality and hero worship for certain individuals such as Governor Isaac Stevens, Meany was well-liked by his students. On May 6, 1904, he started the tradition of Campus Day, wherein classes were cancelled so students and faculty could clean the grounds. Cheers rang out each year when he arrived.

Meany’s interest in promoting the study of history extended beyond the university. He lectured at various historical societies and had articles published in the local newspapers. In 1903 he honored Chief Joseph by bringing the aged Nez Perce leader to Seattle to meet with the public. Meany was also involved with erecting monuments at American Camp and English Camp in the San Juan Islands (home of the famous Pig War) and at the site the Denny Party landing at Alki Point in 1851.

A-Y-P Exposition

In 1906, Meany began work on two of the most notable projects of his career. The first was the publication of the Washington Historical Quarterly, a scholarly journal which is still published today under the name Pacific Northwest Quarterly. The rest of his time was taken up with promoting the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition, which started out as celebration of the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897, and expanded into a World’s Fair.

As one of the committee members, it was Meany who successfully argued that the University be used as the site, noting that some of the buildings could be used for much-needed classrooms after the fair had ended. He also insisted that educational exhibits would take precedence at the exposition as a way of highlighting the achievements and progress that had been made throughout the region.

At the end of 1906, Meany traveled east and secured participation from the state of New York, home of U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward (1801-1872), who had negotiated the purchase of Alaska in 1867. He also met with artists Richard E. Brooks and Lorado Taft, who would sculpt statues for the exposition of Seward and George Washington respectively. Of course, Meany also lectured at many of the Ivy League colleges during his trip, and got to visit many historic sites throughout the East Coast.

High Honors

The Meanys welcomed the birth of another son in April 1907, and although his students suggested such names as “A-Y-P,” “Isaac Stevens,” and “Campus Day,” the boy was christened Edmond S. Meany Jr. As busy as the professor was that year, he also found time to travel to South Dakota with noted Seattle photographer Edward S. Curtis to photograph and interview Sioux Indians.

The A-Y-P opened on June 1, 1909, and Meany was the main speaker at the unveiling of the Washington Statue on June 14. By the time the exposition closed in October, it was a roaring success, and the first World’s Fair to ever make a profit. Proceeds went to the Anti-Tuberculosis League and to the Seaman’s Institute.

But even with Meany’s busy schedule of teaching, writing, editing, book collecting, lecturing, and promoting, the red-haired professor -- now approaching the age of 50 -- found time for a new avocation: mountain climbing. In 1908 he joined The Mountaineers, a Seattle club, and became the organization’s president for 27 years. Meany eventually climbed the six tallest peaks in the state, as well as his namesake, Mount Meany.

Meany’s History of the State of Washington was published in 1909, and 1912 saw the release of United States History for Schools which earned him high praise. In 1913, he was elected president of the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association. But one of Meany’s greatest accolades came on Campus Day, May 1, 1914, when the Auditorium Building from the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was renamed Meany Hall, an honor usually not bestowed at UW upon living persons.

Changing Times

Meany continued his heavy workload of teaching classes, editing the Quarterly, writing essays and articles, and giving scores of lectures off campus each year. In 1923, he wrote a six-act play called “Americanus,” a patriotic paean to American history. Staged at the University of Washington stadium, with 10,000 singers, musicians, and actors, the pageant was narrated by Clio the history muse, and featured Americanus, who represented the spirit of a Christian nation who guides such luminaries as Washington and Lincoln in their heroic deeds.

But Meany’s romanticized view of the past could not keep up with changing times. By the 1920s, he expressed concern that such things as jazz music, cheek-to-cheek dancing, “vodvil” entertainments, and other “social evils” were leading to a decline in moral values. He even broke long-standing ties with the Post-Intelligencer, and cancelled his subscription when they printed what he felt were lurid details about Hollywood’s Fatty Arbuckle scandal.

Nevertheless, the students still loved and respected the old professor. On Campus Day in 1924, Meany was surprised by a brand new Buick sedan given to him by alumni, students, and dear friends. Meany and his wife reciprocated two years later by dedicating a bench near Denny Hall on behalf of the class of 1885.

At Work Until the End

On September 30, 1929, Meany donated his vast collection of historical documents, photographs, and books to the university -- an accumulation of 35 years effort. The next day, he and his wife were injured in a four-car collision on the Seattle-Tacoma highway, leaving Meany with a broken knee. He was in the hospital for seven weeks, and spent seven more recuperating at home.

When he finally returned to campus -- assisted by a cane -- there was some concern that he might be ready to retire. But the indefatigable professor continued on, even when the Great Depression led to staff cuts within his department. And even though his mountain climbing days were over, he still vacationed with The Mountaineers every summer. In 1931, a contest was held to name a new 17-story hotel in the University District, and the most popular entries were the Hotel Edmond Meany. The Mountaineers also named their stamped-pass ski lodge after him, as well as Meany Crest, a “rugged dome” that they scaled near Mount Rainier.

On April 22, 1935, Edmond Meany was in his office preparing for a 10:00 a.m. class, when he fell over, dead from a stroke. Before the funeral, his body lay in state in Meany Hall for services that were attended by thousands. He was buried in Seattle's Lake View Cemetery, in full view of both the Cascade and Olympic mountain ranges.