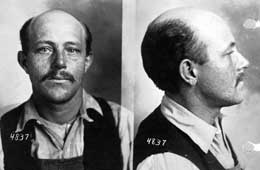

On October 30, 1916, citizen deputies beat 41 members of the militant labor union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), at Beverly Park in Everett. Everett city officials have granted authority to Snohomish County Deputy Sheriff Donald McRae (b. 1868) to restrict the IWW from speaking on Everett’s traditional free-speech corner at Hewitt and Wetmore avenues, an attempt to prevent the IWW from organizing. For their part, on that day 41 members of the IWW, most straight from the harvest fields, leave Seattle by boat and head for Everett in support of an Everett shingle-mill-workers' strike (organized not by the IWW but by an AFL union) and with the intent of pressing the free-speech issue. They arrive in the evening and are met by more than 200 armed deputies who tell them they can only speak at a location away from the center of town. The IWW members refuse, and some are beaten at the dock. Deputies then load them into waiting trucks and cars, drive them to a remote wooded area near the Beverly Park interurban station southeast of town, and brutally beat them.

In darkness and cold rain, deputies formed two lines from the roadway to the tracks and forced the Wobblies, as IWW members were called, to run a gauntlet ending at a cattle guard. One by one the men were beaten with clubs, guns, and loaded saps. A family living nearby was startled by the shouts, curses, cries, and moans they heard and came to witness the brutal scene. The injured were left to return to Seattle any way they could.

The following morning Everett residents were enraged at the stories told of the previous evening’s atrocities. An investigation committee was formed including Rev. Oscar McGill of Seattle and labor leaders Jake Michel (b. 1866) and Ernest Marsh (1877-1963). Despite continuing heavy rain, the committee found the area heavily stained with blood. Marsh officially reported to the State Federation of Labor, “There can be no excuse for nor extenuation of such an inhuman method of punishment” (Smith, 69-70).

The happenings at Beverly Park hung like a cloud over the city, firming both deputies and IWW members in their resolve to win. On November 5th they met again, this time at Everett’s Bloody Sunday, the Everett Massacre, in which two deputies and five Wobblies died in a gunbattle at an Everett dock.