The week of September 21-25, Spokane hosts the 1927 National Air Derby and Air Races. The guiding spirit behind bringing this major aviation event to Spokane is Major John T. “Jack” Fancher (1892-1928), commandant of the 41st Division, 116th Observation Squadron of the Spokane-based Washington Air National Guard. The week of races and aviation feats tips Spokane’s “young aviation industry off dead center and [starts] it rolling to a then incomprehendable future” (McGoldrick, 94).

Mounting Anticipation

When Charles A. Lindbergh (1902-1974) made his epic trans-Atlantic flight on May 21, 1927, aviation riveted national and international attention. Although Lindbergh included Spokane on his subsequent tour of the United States in the Spirit of St. Louis, he was not, contrary to a prevalent local misconception, in Spokane for the National Air Derby. Major Fancher had been on hand to greet Lindbergh upon his return to New York from France and invited him to be Spokane’s guest at the Air Derby. Lindbergh accepted “but had to cancel out in favor of his victory flight around the United States” (French). However, he included Spokane on the tour, and his visit on September 12 added to the mounting anticipation of the Air Derby to begin nine days later.

In 1925, Spokane sponsored a popular “air circus.” In 1925 and 1926, Los Angeles and Cleveland both put on national air races that were not very successful. There was therefore some skepticism as to Spokane’s ability to succeed where these larger cities had failed. However, the Lindbergh triumph had raised public enthusiasm for aviation and, furthermore, Spokane “had in that day a live-wire business community that was willing to put its money where its mouth was and an active Chamber of Commerce” (McGoldrick, 95).

Fancher was the driving force behind organizing and carrying off the air derby, and he enlisted such local leaders as newspaper owner William H. Cowles, lumberman Milton McGoldrick, investment tycoon Harlan I. Peyton, hoteliers Victor Dessert and Louis M. Davenport, and a host of others to contribute their time, financial support, influence, and organizational skills to its success.

This group raised more than $60,000 and spent countless hours in committee work prior to and after the announcement in May that the National Aeronautics Association had awarded the races to Spokane. In July, Sergeant Raymond A. Carroll and Jack Fancher flew to New York and back in the Swallow -- an aircraft belonging to Spokane’s legendary aviator Nicholas B. “Nick” Mamer (1897-1938) -- to drum up publicity and make arrangements along the routes of the races.

The Race to Spokane

The major events of the week were several races beginning in New York and San Francisco and ending in Spokane. Various classes of aircraft, some fast, some slower, competed in a series of races for cash prizes and trophies. Many cities and companies throughout the nation sponsored planes and pilots. Some of the flights were non-stop, while others required planned refueling stops.

Several pilots ran into trouble en route and could not continue. Military planes also participated, but were ineligible for cash prizes. Nick Mamer and Bruce McDonald flew a Wright J5-powered open-cockpit biplane for the Spokane entry and came in third in the Class A race from New York. Washington Air National Guardsmen Tom Symons and Alphonse Coppula won the race for National Guard pilots and planes. The Class A winner of the $10,000 first-place purse in the race from New York was Charles W. “Speed” Holman (1898-1931) of Minneapolis in a Laird plane with a Wright Whirlwind engine. Winners received their trophies from queen and hostess for the event, Vera McDonald Cunningham, selected “because of her charm and ability to sell many advance tickets” (McGoldrick, 141).

Jimmy Doolittle's Trademark Loop

Because of the uncertainties of weather, the exact arrival time of the various races could not be known in advance. Precision air acrobatics, parachute drops, and local closed-course speed races in laps above the field kept eager spectators well entertained as they waited at Felts Field in the specially set up box seats and grandstand, mostly borrowed from the Spokane Parks Department.

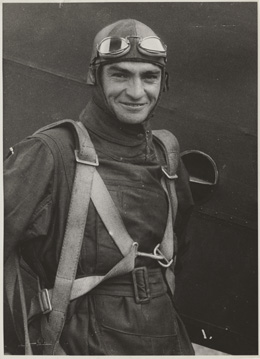

One of the exciting participants in these pre- and inter-race displays was Army Air Corps ace Lieutenant James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle (1896-1993) who, in addition to his official events, buzzed downtown Spokane upside down in one of his trademark “loops.”

As a result of the 1927 National Air Races, “Spokane became known as a leader in our nation for aviation activity for the first time. In the years that followed they were successfully held in Cleveland and Los Angeles and the country went forward into the air age. Spokane had been a part of it” (McGoldrick, 105).