On Saturday, September 5, 1925, a cloudburst in the Wenatchee Mountains in Chelan County sends a 20-foot-high wall of water down Squilchuck Canyon into the small community of Appleyard, killing 16 people and injuring many others. Two known victims are never found and are presumed to have been washed into the Columbia River. Property damage to Appleyard and the Great Northern Railway freight terminal in South Wenatchee is estimated to be at least $500,000.

Appleyard Terminal

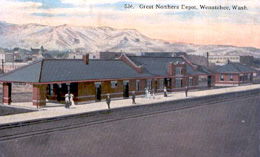

In 1922, the Great Northern Railway (GNR) constructed a large rail yard, suitably named the Appleyard Terminal, along the Columbia River in South Wenatchee to service the burgeoning apple industry. The terminal had 14 sidetracks, each a mile long, where thousands of crates of apples were loaded into hundreds of boxcars and iced for shipment across the United States and around the world. Numerous steam locomotives were maintained in the roundhouse for the arduous trek across the North Cascade Mountain Range.

The town of Appleyard, a settlement of approximately 500 people, mostly railroad workers, was located immediately west of the Appleyard Terminal, two miles south of Wenatchee, near the mouth of Squilchuck Canyon. Businesses included two cafes, two hotels, a gasoline service station, a meat market, and a grocery store with a post office. Five small houses had been built on the site of a former auto-campground near Squilchuck Creek, and others were under construction.

In 1923, the town's first postmaster, Carl E. Emmett, named it "Delicious" after the apple, but the name never took hold. The second postmaster, Clifford C Daniels, had the name of the post office changed to simply South Wenatchee in January 1925. Wenatchee residents usually referred to the town as Terminal.

Squilchuck Creek

"Squilchuc" is a Chinook Indian word meaning "brown or muddy water." Squilchuck Creek, a tributary of the Columbia River, has its headwaters in the Wenatchee Mountains, part of the Cascade Range. Squilchuck Creek was of sufficient size and volume to power a generator which provided Wenatchee's first electric lights in 1923. To help protect the Appleyard Terminal from flooding, GNR built a huge culvert underneath the train tracks to carry the water from Squilchuck Creek through to the Columbia River. But these preventive measures proved to be insufficient protection from flash floods resulting from cloudbursts in the mountains. There had been flash floods on Squilchuck Creek in the past, some of which had been serious and caused considerable damage.

Many of the passages through Squilchuck Canyon were narrow. Occasionally, torrential rains, high in the mountains, caused rocks, trees, and debris to accumulate in the canyon, creating natural dams and artificial lakes. Eventually, the water pressure becomes so enormous that the dam bursts, sending a wall of water cascading down the canyon, obliterating everything in its path.

The Catastrophe

At about 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, September 5, 1925, a Wenatchee Reclamation District employee recorded that water levels in the irrigation canals were rising rapidly, indicating heavy rainfall in the mountains. By 3:30 p.m., the canals had filled to overflowing and had to be closed to prevent damage to the irrigation system. At 4:15 p.m., without warning, a wall of water, some 20 feet high and 100 feet wide, burst from the mouth of Squilchuck Canyon into Appleyard, which had been unwisely built on the Squilchuck Creek floodplain.

The flash flood wiped out a six-acre tourist auto-campground, crushed houses, and ripped the three-story Springwater Hotel from its foundation, sending the top two stories crashing into the New Tourist Hotel, 60 feet away, and blocking the Wentachee-Malaga county road. Occupants of the hotels heard the water advancing and most escaped without injury. The deluge continued into the nearby Appleyard Terminal, derailing six locomotives and damaging hundreds of boxcars loaded with fresh apples for market. Water, six feet deep, raged across the rail yard for 15 minutes, depositing over a 10-acre area tons of debris including trees, stumps, large boulders, parts of houses and buildings, and several automobiles. Mud and silt spread over the yard, in some places four feet deep.

Frantic Efforts at Rescue

As soon as the flood waters subsided, more than 150 rescue workers began a frantic effort to locate survivors thought to be under the mud and tangled wreckage, and to recover bodies. The group included firefighters, police officers, doctors, nurses, railroad workers, bystanders, and 46 Washington National Guard soldiers. The Salvation Army and Red Cross set up aid stations nearby, providing the refugees and rescue workers with hot coffee and sandwiches.

The Wenatchee Fire Department brought pulmotors to the scene, hoping to resuscitate causalities. However, the recovered bodies had been crushed to death, not drowned. The Great Northern Railway immediately dispatched relief trains from Everett and Spokane carrying cranes, steam shovels and other heavy equipment to help clear the yard of mud and debris. Emergency crews worked for hours to clear and repair the mainline tracks so that six stalled trains could move through, and flat cars carrying heavy equipment could be delivered to the scene.

Finding the Dead and Injured

As officials compiled a list of missing people, rescue teams continued probing the mud and debris throughout the day, finding several victims who had survived the flood. The injured were taken to Saint Anthony Hospital in Wenatchee where they were treated for broken bones, cuts, and bruises. By nightfall, the bodies of seven victims had been located and by following afternoon, five more bodies had been recovered. But four people were still known to be missing, and officials feared there could be many more victims who had been in the auto-campground.

All 12 victims, virtually stripped of clothing, had been found in a huge pile of mud and debris that had accumulated against three long GNR freight trains that were preparing to leave the terminal. The loaded freight cars created a barrier, which prevented the bodies and most of the debris from being swept into the Columbia River. Rescue workers carefully combed through the huge pile of detritus until they were sure there were no more victims to be found.

By Monday afternoon, September 7, 1925, GNR crews, using heavy equipment, had cleared and repaired the mainline tracks adjacent to the terminal and, once again, trains began running on schedule. By nightfall, Chelan County authorities had assumed full responsibility for the disaster scene, relieving the exhausted volunteers. Chelan County and the Great Northern Railway agreed to join forces in the cleanup, a task estimated to take weeks. County commissioners appropriated $1,500 to hire 50 contract workers to begin clearing wreckage and debris from the rail yard using GNR equipment.

The 13th victim, Letha Smyth, age 31, was found about 11:00 a.m. on Wednesday, September 9, 1925. Portions of her clothing had been found and identified on Monday and Tuesday, but the body was found near the Schrock-Nelson meatpacking plant, a considerable distance from where the other bodies had been unearthed. The 14th victim, Florence Emeline McDonald, age 2, was discovered about 6:00 p.m. Wednesday in large pool of muddy water near the roundhouse. She had been sitting in an automobile with her mother, Mrs. Margaret E. McDonald; her older sister, Bernice, age 4; and a neighbor, Mrs. Ellen Butts, in front of the Springwater Hotel when the flood hit Appleyard.

A Sad Day

Margaret McDonald had driven from Leavenworth to pick up her husband, Dominick, a GNR locomotive engineer. After the water subsided, the automobile was found sitting in the rail yard, empty. Margaret's body was found in the yard late Saturday evening. Rescue workers pulled 4-year-old Bernice from the wreckage of a dislodged house early Sunday morning. She was alive and relatively unscathed, sheltered in the arms of Ellen Butts, who had drowned in the flood. The last two known victims, Donald Frederickson, age 15, and Jack Housener, age 5, were never found and searchers presumed the bodies had been washed into the Columbia River.

All of the other names on the missing persons list were eventually accounted for. Many of the victims had been in the houses swept away by the huge wall of water. Fred W. Groff, a GNR yardman, lived in a house located a half-a-mile up Squilchuck Canyon, with his wife, Alma, his seven children, and his sister-in-law, Etta M. Palmer and her 4-month-old son, Louis. Groff was working in the freight yard when the flash flood hit Appleyard Terminal. He watched in horror as the wreckage of his house floated by.

As soon as he was able, Groff, assisted by other yardmen, searched the collapsed house, finding Alma, and his son eldest son, Harold, age 11, alive, but seriously injured. The men continued to search the wreckage, finding the bodies of Groff's four youngest children: Mary, age 8, Alice, age 6, Florence, age 4, and Chester, age 1. Groff found out later that his two eldest daughters, Irene, age 16, and Rosa, age 15, had escaped the flood uninjured. His sister-in-law, Etta Palmer, also escaped with serious injuries, but her 4-month-old baby son, Louis, had been torn from her arms and was missing.

Unsung Heroes

Among the mostly unsung heroes of the disaster were Lillian M. Lovegrove, age 24, a clerk in the GNR yard office and Mr. E. W. Sutherland, age 38, a GNR locomotive engineer. Lovegrove was credited with preventing a train wreck. She notified the dispatcher to stop eastbound GNR passenger train No. 4 leaving the Wenatchee Train Depot just as the flood waters swept across the mainline tracks, ripping up the rails and depositing tons of debris. Then she spied the naked form of baby floating among the debris, ran from her office, grabbed the baby by the arm and pulled it to safety. The baby turned out to be little Louis Palmer. His rescue was, at least, a small compensation to the Groff family who had lost their four youngest children and their house in the flood.

Engineer Sutherland had just brought in a freight train from Everett when the flood reached the terminal. From his cab, he saw a little girl being carried by the torrent toward the Columbia River. He jumped into the water and rescued the girl, and then saw a young boy clinging to an overturned boxcar. After tying a rope around his waist, Sutherland swam to the boy, and then bystanders pulled them both to safety. Sutherland joined the search parties and spent the next two days searching the wreckage for victims.

Cleaning Up Appleyard

Work crews cleared and repaired all the sidetracks in the freight yard for use within two weeks of the disaster, but it took 250 men using steam shovels and heavy equipment, two months to clear away all the debris left by the flood. In addition, GNR had to make substantial repairs to the yard office, roundhouse, turntable, and several other vital buildings and facilities before becoming fully operational. Two weeks after the flash flood, the top two stories of the Springwater Hotel were still blocking the main county road between Wenatchee and Malaga. The owner, Mr. S. Alexander "Sandy" Chisholm, made efforts to move the structure, but it was too large and had been severely damaged. Ultimately the hotel had to be torn down and then rebuilt on its foundation.

At first officials feared the flash flood had wiped out all the apple orchards along Squilchuck Creek, but a subsequent inspection by the Department of Horticulture revealed that very little damage had been done to the trees. The most significant damage was short-term, done by a fierce hailstorm, which pelted 600 acres of apple trees in East Wenatchee, Rock Island, and Wenatchee Heights that same Saturday afternoon. Inspectors estimated that 500 boxcars of premium grade apples, worth approximately $200,000, had been ruined. The damaged fruit was relegated to the manufacturers of apple juice and applesauce. Insurance adjusters estimated the property damage in South Wenatchee and the GNR terminal to be at least $500,000.

Casualty List

Known dead:

- Ellen Butts, age 45, housekeeper, Leavenworth

- Alice Sophie Cleven, age 38, cook, Wenatchee

- Alma Ernst, age 11, Wenatchee

- John William Evans, age 63, fruit farmer, Wenatchee

- Alice Myrtle Groff, age 6, Wenatchee

- Chester George Groff, age 1, Wenatchee

- Florence Eleanor Groff, age 4, Wenatchee

- Mary Josephine Groff, age 8, Wenatchee

- Margaret E. McDonald, age 35, Leavenworth

- Florence Emeline McDonald, age 2, Leavenworth

- George Alex Murdock, age 36, lineman, Entiat

- Wilbert E. Overman, age 27, electrician, Wenatchee

- Paul Russell Pettit, age 24, GNR brakeman, Everett

- Letha Smythe, age 31, Wenatchee

Known missing:

- Donald Frederickson, age 15, Wenatchee

- Jack Housener, age 5, Wenatchee