On October 30, 1947, Jake Bird (1901-1949), a 45-year-old transient, breaks into the home of Bertha Kludt and her daughter, Beverly June Kludt, and hacks them to death with an ax. Two police officers, sent to the Tacoma residence to investigate reports of screams from inside the residence, see a man run out the back door and give chase. Bird is captured and taken to the Tacoma City Jail where he confesses to the killings, claiming it was a burglary gone bad. On November 26, 1947, after a three-day trial, a Pierce County Jury convicts Bird of first-degree murder and recommends the death penalty. While on death row, Bird confesses to committing or being involved in at least 44 murders during his travels across the country. He is hanged at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla on July 15, 1949. Although the case fails to capture the attention of the national press, history marks Bird as one the nation’s most prolific serial killers.

Screams and a Chase

At 2:30 a.m. on Thursday, October 30, 1947, Tacoma Police Officers Andrew P. Sabutis and Evan “Skip” Davies were dispatched to 1007 S 21st Street to investigate reports of screams emanating from inside the residence. As they approached, a barefoot man ran out of the back door into the back yard and crashed through a picket fence. The two patrolmen immediately gave chase.

After scaling several more back yard fences, the fugitive was finally stopped by a high fence and cornered in an alley behind 2122 S "J" Street. He pulled out a jackknife and then attacked the officers, cutting Davies’ hand and stabbing Sabutis in the shoulder. Officer Sabutis, a former prizefighter known as “Tiny” LaMarr, subdued the assailant with a left hook to the jaw and a kick in the groin. After the fight, the prisoner was taken to the Tacoma General Hospital by Officer John Hickey in a patrol wagon, where he received treatment for head and face lacerations. Sabutis was admitted to St. Joseph Hospital with a severe back wound and Davies had the cuts on his hand stitched and bandaged there.

When police officers entered the residence, they found Bertha Kludt, age 52, dead in her bedroom, adjacent to the kitchen, and the body of her daughter, Beverly June Kludt, age 17, on the kitchen floor. Both women had been bludgeoned to death with an ax, which had been left at the crime scene. Detective Lieutenant Earl Cornelison determined that an attempt had been made to sexually assault Bertha Kludt before she was intentionally slain. Beverly June, hearing her mother’s screams, apparently dashed from her upstairs bedroom into the kitchen where she encountered the assailant and was murdered.

Jake Bird's History

The man captured by Officers Sabutis and Davies was identified as Jake Bird, a 45-year-old transient who had a lengthy criminal record including burglaries, assaults, attempted murder, and murder. Bird estimated he had served about 15 years in various prisons for committing crimes. He was born in Louisiana and left home when he was 19 years old. Over the ensuing years, Bird never stayed in one place for long, preferring the life of an itinerant worker. Often he found employment with the railroad as a section-gang laborer, which allowed him to earn money and keep moving from town to town. It was an occupation that lent itself quite well to his avocation: stalking and murdering women in the towns he visited.

Bird was interrogated by Detective Lieutenant Sherman W. Lyons at the Tacoma City Jail where he dictated and signed a confession in the presence of four police officers. His confession stated that he entered the Kludt residence through the unlocked back door to commit “an easy burglary.” He brought along an ax that he found in a nearby shed, “to bluff off anyone who tried to bother me.” Removing his shoes, Bird sneaked into Bertha Kludt’s bedroom and stole $1.50 from her purse. When he returned to the kitchen, he turned around and found Bertha standing behind him. Bird told her that he only wanted her money and his shoes, and then he would leave. But then suddenly Beverly June grabbed him from behind and a fierce struggle ensued, resulting in the deaths of the two women. Bird added that he thought the policemen would shoot him when they had him cornered in the bushes, so he attacked them with his knife.

Legal Proceedings

On Friday, October 31, 1947, Deputy Prosecutor Earl D. Mann charged Jake Bird in Pierce County Superior Court with first-degree murder, but only in the death of Bertha Kludt. It was customary to file only one charge in multiple homicides where failure to obtain a conviction on the first offense would allow the filing of additional murder charges. Judge Edward D. Hodge (1878-1948) appointed James W. Selden, a former Pierce County prosecutor, as his defense counsel. At his arraignment, Bird pleaded not guilty and the trial was set for Monday, November 24, 1947.

At a motion hearing on November 14, 1957, Defense Attorney Selden requested a change of venue, stating Bird could not get a fair trial in Pierce County. He also asked to be relieved as Bird’s attorney, informing the court that Bird wanted to represent himself. Judge Hodge denied both requests.

Trial began on schedule in the Pierce County Courthouse before Judge Hodge but was slowed by jury selection. Questioning of the prospective jurors revolved around their impressions of the crime gained from the news media and whether Jake Bird, a black man, could get a fair trial. Four jurors were excused when it was learned they had recently served on another first-degree murder trial in which the defendant was convicted and sentenced to hang. By the end of the day, a jury of nine men and three women was selected and court was recessed until 9:00 a.m. the next morning.

The Trial

Trial proceeded at a rapid pace and was concluded in just one-and-a-half days of testimony. Prosecuting Attorney Patrick M. Steele’s strategy was to prove that the death of Bertha Kludt was premeditated, thereby qualifying the defendant for the death penalty. Weighing heavily in the trial was evidence regarding the wanton murder of 17-year-old Beverly June Kludt, who was bludgeoned to death in the kitchen when she came to her mother’s defense. Blood and brain tissue from both victims were found on Bird’s clothing, his bloody fingerprints were found in the house and on the ax and his shoes were found at the murder scene.

The state introduced a surprise witness, Tacoma Police Officer John Hickey, who testified that he and Officer Russell Skattum gave Bird a beating while he was in their custody. Hickey said: “I regret to say that I lost my temper after returning from the Kludt home and viewing the terribly hacked bodies of the two women. I had asked Bird as we sat in the patrol wagon why he murdered the two women. He said he didn’t do it. I asked him who did it then, and he said, ‘It was LeRoy.’ ‘Who’s LeRoy?’ I asked him. ‘Oh, another Negro around town,’ Bird replied. ‘You’re lying,’ I replied, and he looked at me with a smug and insolent look. I know I shouldn’t have done it, but I hit him in the jaw with my fist, knocking him to the front of the patrol wagon. Then I struck him a number of times with my night stick until he said, ‘Don’t kill me.’ That brought me to my senses and we took him to the hospital where a nurse said he wasn’t badly hurt” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer).

Later, when Prosecutor Steele moved to enter Bird’s signed confession into evidence, Defense Attorney Selden strenuously objected, declaring it had been obtained under duress and therefore inadmissible. But Judge Hodge disagreed, ruling there was no relationship between the beating and Bird’s voluntary confessions, and admitted it into evidence. Despite continued strenuous objections by the Selden, the confession was read into the record, then the prosecution rested its case. Defense Attorney Selden rested the defense without calling Bird or any other witnesses to the stand.

Closing arguments were begun on Wednesday morning, November 26, 1947 and the case went to the jury at noon. After deliberating for only 35 minutes, the jury returned its verdict. Bird was found guilty of first-degree murder and the jury voted to impose the death penalty. Bird, who had been impassive throughout the trial, sat unmoved as the Judge Hodge read the verdict. On his way back to the Pierce County jail, Bird asked the five deputy sheriffs guarding him: “What’s all the excitement about?” (The Tacoma News Tribune).

Remarks Upon Sentencing

On Saturday, December 6, 1947, Judge Hodge sentenced Bird to be hanged on the gallows at the Washington State Penitentiary on January 16, 1948. After a motion for a new trial was denied by Judge Hodge, Defense Attorney Selden told the court he had done everything in his power to defend Bird and that no further appeals would be made on Bird’s behalf. Then Selden declared: “I feel whenever any man 45-years-old gets an idea that no lives are safe to anyone, except his own, that man is a detriment to society and should be obliterated” (The Tacoma News Tribune).

When Judge Hodge asked Bird for comment, he declared, “I was given no chance to defend myself. My own lawyers just asked you to hang me. They apologized for defending me. If they were so reluctant to defend me, why did they contest the prosecutor’s proof of murder, and now say that everything is proven?” (The Tacoma News Tribune). At the end of his 20-minute impassioned speech, Bird declared: “All you guys who had anything to do with this case are going to die before I do” (The Seattle Times). It became known as the “Jake Bird Hex.” Within a year, five men connected with Bird’s trial died.

Bird's Past

On Sunday, December 7, 1947, Pierce County Under-sheriff Joseph E. Karpatch and Deputy Michael Waverek took Bird in a patrol wagon to the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla to await his execution. Shortly after his arrival, Bird began confessing to his involvement in a dozen murders that took place over a span of 20 years.

On January 6, 1948, at the request of Governor Monrad Charles Wallgren (1891-1961), Pierce County Prosecutor Patrick Steele and Tacoma Police Detective Lieutenant Sherman Lyons went to the penitentiary to listen the confessions. In an obvious bid for a reprieve, Bird offered to tell them more, to “clear his conscience.” Steele told the press: “We want to give him a chance to tell it, but we don’t intend to permit him to use what he might have withheld as a means to add a few days to his life" (The Tacoma News Tribune). Over the next several days, Steele and Lyons took voluminous notes on Bird’s statements, which they compiled into a 174-page report for the Governor’s office.

On January 15, 1948, Bird finally won a 60-day reprieve from Governor Wallgren by claiming that, given time, he could “clear up” at least 44 murders that he either committed or participated in during his travels throughout the country. His confessions brought a throng of investigators from across the nation to interview him at the state penitentiary. Of these 44 confessed murders, only 11 were substantiated, but Bird had more than enough knowledge about the others to be the prime suspect. Police from several states took the opportunity to close the books on many of their unsolved murders. In his travels, Bird had murdered people, mostly women, in Illinois, Kentucky, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Kansas, South Dakota, Ohio, Florida, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, and Washington.

Meantime, Bird appealed his conviction to the Washington State Supreme Court. He personally argued his case before the Supreme Court Justices, stating that Judge Hodge had made several judicial errors and demanded a new trail. On November 30, 1948, his final petition to the state for a retrial was denied and on December 3, 1948, Judge Hugh J. Rosellini (1909-1984) signed another death warrant, ordering Bird to be hanged on January 14, 1949. Bird’s attorney, Murray Taggart of Walla Walla, immediately moved for a stay of execution to permit the filing of an appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals. The motion was granted on the condition the court agreed to review the case.

When the U.S. Court of Appeals refused to review the case, Judge Rosellini set Bird’s execution date for July 15, 1949. Attorney Taggart requested another stay of execution to permit the filing of an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court, but the motion was denied. Undeterred, Taggart filed three more petitions on Bird’s behalf, but the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the case; the last time on July 14, 1949. Bird’s last hope was an act of executive clemency from Governor Arthur B. Langlie (1900-1966), but Langlie chose not to interfere with the execution.

The Hanging

On Thursday night, July 14, 1949, Jake Bird ate his last meal on death row, and then talked with his attorney for two hours. Bird told Taggart he could be a good loser as long as he felt everything possible had been done to save his life. Later that night, he was moved to a holding cell near the gallows, where he was shaved and dressed in new clothes. Just after midnight, Bird walked 10 feet from the cell to the gallows accompanied by Warden Tom Smith and two prison guards. He said nothing to the 125 witnesses who had gathered in the room, but muttered some comment to one of the guards. A volunteer prison chaplain, Reverend Arvid C. Ohrnell, started to read a note from Bird, declaring he bore no malice toward anyone and sought forgiveness. But before he finished, the trapdoor was sprung, dropping Bird five feet to his death.

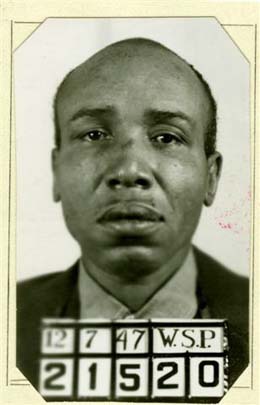

Jake Bird was hanged at 12:20 a.m. on July 15, 1949. His body was taken down 14 minutes later and prison physician Dr. Elmer Hill pronounced him dead. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the prison cemetery, identified only as convict No. 21520. Bird willed his personal fortune, $6.15, to his appeals attorney, Murray Taggart.

Although not formally educated, Bird gained a modicum of fame as a “jailhouse lawyer,” often arguing his own case before the court. His knowledge of the law, together with the help of people against the death penalty, enabled him to delay his execution a year and a half. Bird’s case failed to capture the attention of the national press, even though he confessed to committing or being involved in at least 44 murders throughout the country. But history marks him as one the nation’s most prolific serial killers.

The Jake Bird Hex:

The five men connected with Bird’s trial who died within a year of the “Jake Bird Hex.”

- Edward D. Hodge, Pierce County Superior Court Judge, age 69, died January 1, 1948.

- Joseph E. Karpach, Pierce County Under-sheriff, age 46, died April 5, 1948.

- George L. Harrigan, Pierce County court reporter, age 69, died June 11, 1948.

- Sherman W. Lyons, Tacoma Police Detective Lieutenant, age 46, died October 28, 1948.

- James W. Selden, Bird’s defense attorney, age 76, died on November 26, 1948.

According to The Tacoma News Tribune, all of the men died from heart attacks. A sixth man, Arthur A. Steward, a Washington State Penitentiary guard assigned to death-row, died of pneumonia two months before Bird’s execution.