On Sunday, October 3, 1909, an explosion and fire at the Northwestern Improvement Company's No. 4 mine in Roslyn kills 10 workers. A column of flame 100 to 400 feet high ignites the head frame, tipple, snow sheds, and other buildings. Typically 500 to 600 men work in the mine, but Sunday is a maintenance shift and fewer workers are on duty. Newly developed respirators on display at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle will be rushed to Roslyn to aid in recovery.

Flames Shot Up

The Northwestern Improvement Company was a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railroad and operated a number of mines at Roslyn and Cle Elum. On October 3, 1909, the Sunday maintenance shift was on duty at Mine No. 4, the miners having Sunday off.

At 12:45 p.m. an explosion originating either in the mine or in the shaft shattered the mine. Flames shot up through the main entrance as high as 400 feet and the blast hurtled three men hundreds of feet from the tipple and head frame. They were found badly burned and dead or dying. One man had all his clothing save a shirt cuff blown off his body. The bodies of two other men working on the tipple were never recovered. Apparently the fire incinerated them.

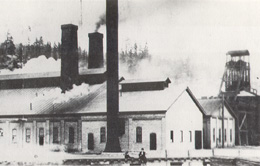

The explosion destroyed the headframe, the tipple, and snow sheds. (The headframe was the timber frame at the top of the shaft that held the pulley that drew the "cage" carrying miners up and down the shaft. The tipple was a large wooden structure that loomed above the shaft. Coal was hauled up the tipple so it could be "tipped" over into waiting coal cars.) The nearby powerhouse and other structures also caught fire and burned. The fire threatened other mines in the vicinity.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer covered the accident for two days with headlines, illustrations, and photographs of the mine and the dead:

"Without warning of any kind the terrific explosion shook the town and broke windows half a mile away from the mine. A sheet of flame breaking from the shaft reached the height of 180 feet and hung suspended for several seconds. There were two distinct explosions which followed close after each other like the discharge of both barrels of a shotgun. The tipple over the shaft and the other outbuildings instantly broke into flame and were blazing furiously before the nearest spectators got to the scene."

The Seattle Daily Times did not have a reporter on the scene and relied upon telegraphic accounts of the tragedy. Nonetheless its headline proclaimed:

"Thirteen Die in Explosion at Roslyn, Bodies Hurled High in Air, Burned and Horribly Mangled Stripped of All Clothing by Terrible Force. The story went on to say that five men who were working about the tipple at the mouth of the shaft were hurled high into the air, enwrapped in a heavy sheet of flame. The awful force of the explosion was shown by the fact that the clothing of all four [sic] was stripped from them; the intensity of the heat by their fire-blackened bodies, burned past recognition in the instant's exposure to the flames."

The paper further reported on the injuries and death of James Gurrell, a 50-year-old, American-born laborer:

"Gurrell, horribly mangled and charred with both eyes burned out and with only one shirt cuff of his clothing left on him, was found half-buried in a pile of sawdust 500 feet from the tipple upon which he had been working. Despite his awful injuries he was still conscious. Several of Gurrell's children were returning from church when they saw the explosion. They ran to the scene and almost immediately found their dying father. Their broken-hearted cries and manifestations of grief was the saddest feature of all the sad picture. Gurrell lived only a few hours."

The Times got the count of dead wrong and reported no further on the matter.

Every Heart Struck with Fear

According to the Times and the Post-Intelligencer, "thousands" of people gathered within 10 minutes. "Every heart was struck with fear, for there came to all the instant realization that it would be impossible immediately to learn who were the victims." Mine Superintendent John G. Green organized men to fight the fires and for the next 48 hours a stream of water was directed down the shaft.

The force of the explosion stopped the ventilation fans and Green had them run in reverse to try to keep the fire from working into the mine. On Sunday night, rescuers entered the mine, but were blocked by a cave-in on Slope No. 1. Then members of the crew were overcome by "afterdamp" (the poisonous gasses left in a mine following a fire and explosion, usually including carbonic acid gas and nitrogen) at the 3,000-foot level of Slope No. 2 and had to be rescued themselves.

Technology of Rescue

On Monday evening, two "Draeger helmets" (Inspector of Coal Mines) arrived in Roslyn from the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle where they were on display as part of the mining exhibit. Superintendent Green did not issue them immediately because no one was trained in their use.

Green ordered bratticing (wood and canvas partitions) down the No. 1 Slope to the fifth east level. Men then sealed off the slope, which sent fresh air to the east side. Teams picked their way past collapsed roofs to the mule barn (draft animals were used in the mines and lived out their lives underground) and one rescue group was trapped for half an hour by a fallen roof.

By Thursday, men had been trained in three Draeger units, but two of the units had air bottles with a capacity of only about one hour each. With bratticing and the air units the teams found the body of pumpman J. E. Jones. Even with the Draeger units, the team had to turn back when there was insufficient oxygen for their safety lamps.

On Friday evening, the Draeger-equipped team found two tracklayers on the 11th level, but "bad air" and wreckage prevented recovery of their bodies until Saturday. The explosion had so damaged the mine and fire had burned so many timbers that the last two bodies, those of tracklayers Daniel Hardy and Dominick Bartolero, were not recovered until the following April. The severe damage prevented any conclusive discovery of the origin or the cause of the explosion.

State Inspector of Coal Mines David C. Botting examined several possible causes and believed that the most likely cause was a spark from electrical equipment, which ignited a small pocket of gas. The morning of the explosion, mine officials had taken some electricians to the 14th level of the mine to show the action of gas in a safety lamp, but they could not find enough gas to demonstrate how the lamps worked. Other inspections that weekend showed no unusual hazards.

The coroner's jury found that the men died from an explosion "fire damp" (the old term for methane gas), but the jury could not determine the cause of the explosion.

The Victims

The dead men left nine widows and 21 orphans. They were:

- Aaron Isaacson, age 26, laborer, Danish

- Otis Newhouse, age 38, outside foreman, American

- J. E. Jones, age 20, pumpman, American

- Carl Berger, age 48, carpenter, Danish

- William Arundell, age 44, miner, English

- James Gurrell, age 50, laborer, American

- Philip Posovich, age 30, track layer, Austrian

- Dominick Pomotich, age 33, track layer, Austrian

- Daniel Hardy, age 60, track layer, English

- Dominick Bartolero, age 42 Italian