In 1866, brothers William, George, and John Hume, along with Andrew Hapgood, begin operating a small cannery on a scow at Eagle Cliff in eastern Wahkiakum County near the Cowlitz County line in southwest Washington. The Eagle Cliff cannery marks the start of the salmon canning industry that will flourish along the lower Columbia River for the rest of the 1800s before declining in the twentieth century along with the river's once-massive salmon runs.

For centuries the Columbia River teemed with uncountable numbers of salmon. In most years, three different runs of chinook salmon, the species that was both largest in size -- with some fish topping 60 pounds -- and most numerous, along with runs of sockeye, coho, and chum salmon, made their way up the river. Indian peoples from the river's mouth to its source in the Canadian Rockies depended heavily on the salmon for food and trade. They used sophisticated technologies including channels and weirs and platforms with dip nets or spears to harvest huge quantities of fish in a short period of time during peak runs. They preserved most of the catch for later consumption and trade by drying it -- smoking fish over fires in the wet climate of the lower Columbia and relying on sun and wind east of the mountains.

Starting an Industry

Early non-Indian traders and settlers in Wahkiakum County and elsewhere along the Columbia also relied on preserved salmon, purchasing dried fish from Indian villagers or salting fresh fish. But it was canning technology that turned Columbia River salmon into a product available around the world and within less than a century helped bring about the decline of the tremendous fish runs on which the industry was built.

William and George Hume, who had sold fresh and salted salmon from the Sacramento River in California since the 1850s, began the Pacific salmon canning industry there in 1864. They brought Andrew Hapgood, an old friend from their home state of Maine, who was a tinsmith with some experience canning lobster and salmon on the east coast, to operate a cannery in Sacramento. After two years, they found the Sacramento River runs insufficient to supply the cannery and moved to the Columbia in search of more salmon.

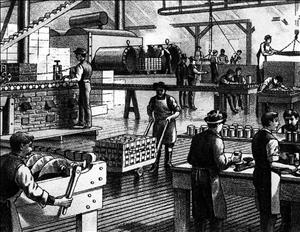

Hapgood and the Humes started canning salmon on the Columbia River in 1866 at Eagle Cliff in Wahkiakum County, some nine miles east of Cathlamet, the county seat. In the beginning, two two-man boats, one crewed by William Hume and his brother John and the other by George Wilson and another man, were sufficient to supply all the fish that the small cannery, located on a scow, could process. Hapgood did the cooking and canning, using a secret recipe that was still a trial-and-error procedure. An early settler wrote that judging by "the appearance of the cans floating along the shore below this Eagle Cliff cannery ... vast must have been the losses of the first trial canning salmon on the Columbia" (Martin, 74). Nevertheless, the cannery managed to produce 4,000 cases of canned salmon (a case holds 48 one-pound cans) in its first year of operation.

Canneries Flourish

Canned salmon was valued in the east, Australia, Great Britain, and elsewhere as a nutritious and inexpensive food for workers and their families. Columbia River salmon quickly became popular and profitable and the Humes and others built more canneries along Wahkiakum County's river shore. George Hume, with Isaac Smith, began a second cannery at Eagle Cliff in 1868. Frank Warren built at cannery at Cathlamet in 1869 and four years later another Hume, Robert, built one at Bayview, a mile downriver from Skamokawa. Also in 1873, Joseph Megler, who went on to a prominent political career, opened a cannery at Brookfield. In 1878, John Temple Mason Harrington built the Pillar Rock Cannery, named for a prominent basalt column rising high above the river's surface that featured prominently on the cannery's labels.

Many canneries also sprang up outside Wahkiakum County, more than 50 in all on the lower Columbia and its tributaries. Astoria, Oregon, alone boasted 25 canneries. In 1895, Columbia canneries produced 635,000 cases of salmon. Many of the laborers who did the difficult and dirty cannery work were Chinese immigrants. George Hume employed the first Chinese workers in 1872 and they proved so efficient that by 1881 more than 4,000 Chinese men were working in Columbia River canneries. In the 1880 census, 551 Chinese -- nearly all of them male cannery workers -- accounted for nearly one third of Wahkiakum County's total population. The percentage declined after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and few of the single male workers settled permanently in the county.

Other immigrants, a large percentage of them from Scandinavian countries and the Balkans, caught most of the fish processed in the canneries. Cannery owners rented small boats and nets to the fishermen. The two-man boats, powered by sail and oar, dragged long gillnets -- generally at night so the salmon wouldn't see them -- on which the salmon were caught by their gills. Historian Richard White notes that while one gillnet boat's catch was small, the fleet of nearly 2,000 boats "covered the river below Portland from May to August. Their nets formed a vast floating barrier to salmon -- 545 miles long by the late 1880s if connected and stretched end to end" (White, 40).

The Decline

By that time the prodigious salmon runs were already declining as the gillnet fleet, along with shore-based fishing methods such as seine nets, pound nets, fish wheels, and fish traps sharply reduced the numbers of fish that made it back upriver to spawn. Combined with the 1893 depression, the declining runs forced a number of canneries to close. World War I prompted a brief upsurge in the number of canneries, but the depression of the 1930s brought more closures.

Continued overfishing, deteriorating habitat, and eventually dam construction contributed to further declines in numbers of salmon and the virtual disappearance of the prime spring and summer chinook that were the source of the premium product for which Wahkiakum County canneries were known. In 1947, just 81 years after the Humes' first cannery opened, the last salmon were canned in Wahkiakum County as the Altoona and Pillar Rock canneries closed. (The Pillar Rock brand survived the cannery; in 2006 canned wild Alaska salmon is still sold under that label in parts of the country.)

Canneries elsewhere, especially in Astoria, continued to operate for several decades, partly by diversifying to can bottom fish, tuna, and crab along with salmon. The last cannery on the Columbia closed in 1980.