Inglewood, a community on the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish in eastern King County, is often confused -- though it should not be -- with a town platted in the 1880s by Ingebright Wold south of Lake Sammamish known as Englewood; this later became Issaquah. Nor should it be confused with the Inglewood community in the southern part of Kenmore, which came along in the 1950s and is today (2007) primarily known for its golf course. Inglewood was located on the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish. It was an almost-town which instead became a community between the 1890s and the 1930s. Its legacy lives on in what is today the northern part of the city of Sammamish.

A Plat Without A Town

The town of Inglewood was platted on July 30, 1889 by Paul Hutchison and several others whose names are apparently lost to history. Kroll Atlas maps from the early twentieth century show that the plat formed a square starting on the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish and running east along NE 16th Street (just north of Inglewood Hill Road) to 212th Avenue NE, then south across Inglewood Hill Road to NE Eighth Street, west back to the lake, and then north again. This same platted area still shows as “Inglewood” on some of today’s modern maps of the city of Sammamish, although the name today is meant only to identify the neighborhood.

But though it was platted, Inglewood was a plat without a town. No town was ever built there. Legend has it there were plans to build a lumber mill at the foot of the hill (probably near today’s intersection of Inglewood Hill Road and East Lake Sammamish Parkway) and the Inglewood town site was intended to house employees of the mill, but before that happened the logging industry took a downturn, perhaps caused by the depression of the mid-1890s.

The Inglewood Post Office

Only three weeks after the town was platted, the Inglewood Post Office was established on August 21, 1889. John Ayer was the first postmaster. Between 1890 and 1894 both Charles Gunther and his wife Theresia ran the post office. Ramsey writes about mail delivery at the time:

“The Inglewood [post] office was in the Gunther store building and taken care of by all members of the Gunther family. Mail came from Seattle and dispatched the same day. The mail came on the railroad, which at that time was the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway. The train consisted of a combination mail-and-baggage car and two coaches and had no regular schedule. Patrons on the line just waited. The whistle was the signal for the postmaster to make up the mail, and he had plenty of time.”

The Gunther store was located along the Seattle Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad line (taken over by Northern Pacific in 1901), very close to where Inglewood Hill Road intersects with East Lake Sammamish Parkway today. A small railroad depot was built just below the store, probably sometime near the turn of the twentieth century.

In June 1907 the post office moved about a mile and a half north, to the Lake Sammamish Shingle Company, and Joseph Weber (1865?-1937) became the postmaster. This post office, also known as “Sammamish Station” (after the little community of Sammamish at the mill site), likely operated out of a large building that also served as a company store, office, cookhouse, and bunkhouse. By 1907 Weber had two shingle mills on the site.

Ramsey writes that Weber was so busy with his mill(s) that his accountant, Will Quackenbush, (1879-1973) did most of the post office work, and many people thought he was the postmaster. There was a rail stop in Sammamish too. It was not an actual depot, but was more like a loading platform. It saw plenty of activity during Weber’s day.

In 1916 or 1917 Joseph Weber’s son John began managing the Inglewood Post Office. Like Joseph Weber, John also had his hands full: An 1918 East Side Journal article noted that he was auctioning his herd of dairy cows at his dairy barn in Sammamish in order to have more time for his other enterprises. Still, John Weber ran the post office until it closed on February 28, 1923, at the same time that the railroad discontinued passenger and mail service through Inglewood. The shingle mill at the site continued operating for nearly another eight years, closing in December 1930.

The Inglewood Community

There is no record of Inglewood in the 1900 United States Census. A 1901 Polk’s business directory lists the Inglewood community with a population of 25. But the community’s growth accelerated rapidly during the first decade of the twentieth century, aided in no small part by the establishment of the Lake Sammamish Shingle Company by Joseph Weber in September 1901 and the addition of a second single mill several years later. By 1910 the Inglewood community had come into its own, and made its first appearance in the Census. The Inglewood census precinct covered a far larger area than the town plat of Inglewood itself, running from the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish north of where the shingle mills were located at today’s Weber’s Point, east to at least as far as 244th Avenue NE, south to SE Eighth, and then west back to the lake. The Inglewood precinct essentially covered what is today considered the northern half of the city of Sammamish.

The 1910 Census for the Inglewood precinct paints a considerably different picture of the local population than what exists there a century later. In April 1910, 185 non-Indians were recorded in the Inglewood precinct, living mostly on or near the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish. More than 30 percent of these inhabitants reported they had been born in countries other than the United States; two-thirds of those came from the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Few non-Indians were actually “from” Inglewood. In fact, only 20 percent of these inhabitants reported that they had even been born in Washington state, and of these 36 people, all but five of them were under the age of 21. Most of the men of the household (and some of their sons) worked either at the Lake Sammamish Shingle Mill at Weber’s Point or at a logging camp in the area.

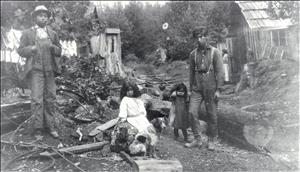

The 1910 Census also has a separate section that lists 45 Indians living in the Inglewood precinct. This represented 20 percent of Inglewood’s total population, Indian and non-Indian combined. With only a couple of exceptions (children that were adopted into one family), all of these Indians were listed as being from the Snoqualmie Tribe. No one seems to know precisely where the Indians lived in Inglewood. One resident living in Inglewood in 1910, Anna Clark Fortescue, said years later in an interview for the Marymoor Museum Library that there was an “Indian cemetery right by the lake” (Bellevue Journal-American), and others have made vague references to Native American families living close to Lake Sammamish, possibly near the foot of Inglewood Hill.

However, property records from the early 1910s do not identify any Native American families owning property in the Inglewood precinct. (Other records from the same time period, as well as the 1920 Census, show additional members of the Snoqualmie Tribe living just south of Inglewood, near Monohon.) By 1930, although the total population in the Inglewood precinct was little changed from 1910, the Indian population had declined from 45 to eight, and all of these were from one family. Property records from 1930 show some of them owning property along the western edge of Thompson Road near East Lake Sammamish Road, as it was then known.

Logging In Inglewood

Logging was underway on the Sammamish Plateau by 1890 and during the early decades of the twentieth century was in full swing, with operations reaching well out onto the Plateau. The biggest local players in the local lumber business in the early decades of the twentieth century were C. P. Bratnober (1866-1928) and John Bratnober (1879-1951) of the Allen and Nelson Mill Company (later the Bratnober Lumber Company) in Monohon, and the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company.

Although there was extensive logging in Inglewood in the early twentieth century, there was no lumber mill in Inglewood. There was, though, a pier for some years near the foot of Inglewood Hill Road where boats traveling the lake picked up logs bound for nearby mills. There also appears to have been a logging camp in the area in the early twentieth century. But the nearest lumber mills were the Allen and Nelson Mill (which became the Bratnober Lumber Company in 1924) three miles south in Monohon, and Campbell’s Mill (which burned down, also in 1924) three miles north in Adelaide. Campbell’s Mill was located in what is today extreme southeastern Redmond, just north of 187th Avenue NE and East Lake Sammamish Parkway. By 1930, most of the area along the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish and in the hills just above the lake had been logged out and logging operations had moved several miles east onto the Plateau. By the 1940s, much of this inland area on the Plateau was logged out as well. After that time logging was less of a driving force in the local economy.

Inglewood Grammar School

There were lots of children in early Inglewood, and there was a school there for them too: The Inglewood Grammar School. The school was probably built in the early 1890s -- it is documented to be in existence in 1895 -- and operated until 1920, when it consolidated with other small area schools into the Redmond School District. It was located on the southeastern corner of NE Eighth Street and 228th Avenue NE in Sammamish, near where the Sammamish 76 service station is located today in the Sammamish Highlands Shopping Center. Originally built as a simple log building, by 1900 the school had been replaced by a more substantial structure. The school was a traditional one-room school, complete with cloakroom and porch in the newer building. One teacher taught students from first through eighth grades, and the students were seated in rows according to their grade.

About 1910, Anna Clark Fortescue taught there; in her last year she had 24 students, which included five Native Americans. Fortescue said she was so busy with the full class that she had some of her older students help with the teaching. The school’s students lived near the foot of Inglewood Hill and up on the Plateau itself. Students living farther north and west in Inglewood (near the shingle mill, for example) attended closer schools in Redmond and Happy Valley.

The Inglewood Grammar School closed in 1920 but served as a community center later in the decade. Around 1930 Floyd and Ruby Eddy bought the land and made the building their home for four or five years. Later in the thirties the building was rather ignominiously converted to a chicken coop and eventually fell into disuse. The building itself survived into the 1970s before collapsing from neglect, and is still remembered by many today living on the Sammamish Plateau.

Inglewood Store

By the 1920s a gas station and grocery store were operating on the west side of East Lake Sammamish Road just north of Inglewood Hill Road. In 1929, Leo and Lena Schaller began running the gas station and store. The store served as a polling place through at least the 1930s and early 1940s, and both Leo and Lena served as precinct committeemen for the Inglewood voting precinct. The service station operated until 1944; afterward, Lena Schaller converted the business into an antiques shop.

By the mid-1970s the store was closed. But the building soldiered on intact into the twenty-first century, a silent sentinel to Inglewood’s earlier, quieter years as development erupted on the Sammamish Plateau during the last quarter of the twentieth century. In 2003 the building seemed to vanish overnight when it was quickly torn down and hauled away with no fanfare, and with it one of the final links to Inglewood’s past vanished.

Gone, but not forgotten. An area map on Page 8 of the December 2006 Verizon telephone directory for the Eastside (of Seattle) lists “Inglewood” on the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish, a reminder that the past lives with us in the present.