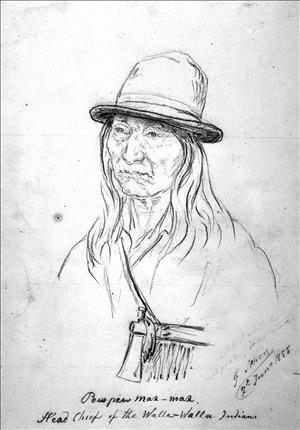

On December 7, 1855, a four-day battle begins between Oregon volunteers and the Walla Wallas and other tribes. Tensions have been growing that year between many of the Native American tribes of the interior Pacific Northwest and the increasing numbers of newly arriving settlers. Some tribes have been coerced into signing treaties that grant most of their ancestral lands to the United States, whose citizens are beginning to crowd into the area. The Yakamas, under the leadership of Kamiakin (ca. 1800-1877) and others of his family, were in open defiance of encroaching non-Native settlers and battled with volunteer territorial militias. With their resistance reduced, the territorial volunteers turn to other tribes that have been asserting themselves, including the Walla Wallas under their chief, Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox. Marching into their stronghold in the Walla Walla River valley, the First Oregon Mounted Volunteers defeat the Walla Wallas and their allies in a four-day running battle. Before the fight, chief Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox had been taken hostage and, during the first day of the battle, he and other hostages are killed. The Walla Wallas will never fully recover from the campaign. The next year, federal troops will take over the fighting and, following a series of battles during 1858, most Indian military resistance in the interior Pacific Northwest will be defeated.

Entering Walla Walla Country

In late November 1855, Oregon Territorial Governor George Curry (1820-1878) ordered units of the Oregon Mounted Volunteers to march on the Walla Walla Country. Major Mark Chinn left The Dalles with about 400 men. On November 17, the force camped at Wells Springs, Oregon. There they were met by John McBean and Augustin DeLore. These men had been sent by Narcisse Raymond to implore for protection for white and French/Indian half breeds (Metis) living in the Walla Walla Valley, who feared for their safety and their possessions. Fort Walla Walla, near the mouth of the Walla Walla River, had been burned and several homes in the valley had been razed as well. It was thought that Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox was waiting with perhaps 1,000 warriors.

Major Chinn assembled six companies of the First Oregon Mounted Volunteers near the Emigrant Road (Oregon Trail) crossing of the Umatilla River, near what is now Echo, Oregon. Buildings of the Umatilla Indian Agency there had recently been burned. The Volunteers constructed a stockade and called it Fort Henrietta, after the wife of Major Granville Haller (1819-1897), who had recently campaigned in the Yakima vicinity. On November 29, Lieutenant Colonel James Kelly (b. 1819) arrived at Fort Henrietta to assume overall command of the Oregon Volunteers. He brought Indian Agent Nathan Olney with him, who accompanied the soldiers in the following days. Soon after, Captain Charles Bennett (1811-1855) arrived from The Dalles with more soldiers.

On December 2, 1855, Lieutenant Colonel Kelly led most of his troops out of Fort Henrietta, leaving in the evening to undertake a perilous night time march, in wet, snowy weather, in an attempt surprise the Indians. Finding no opposition, he camped on the Walla Walla River, having come cross-country to this spot located several miles upstream from Fort Walla Walla. In the later afternoon of December 3, a contingent of men left the camp to examine the abandoned post. James Sinclair, the former proprietor of the fort, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, Major Chinn, and others, soon came upon the plundered and partially destroyed adobe building. Sinclair invited the officers to spend the night at his former company store; wind whistling through the walls made for an uneasy sleep.

Skirmishes and Encounters

The next morning, several soldiers skirmished with Indians spotted on the opposite banks of the Columbia River, but they were too far away for their fire to be effective. Kelly’s party then returned to the main force. Later that day a group of Indians approached the camp of the Volunteers. Some soldiers gave chase, in a northeasterly direction, but the faster Indian ponies easily out-distanced the inferior horses of their pursuers. Kelly determined that he would follow in the same direction when morning came.

At dawn on December 5, Lieutenant Major Kelly divided his command. He sent Major Chinn, with the baggage and about 125 men, straight east to wait on the banks of the Touchet River, near where it flows into the Walla Walla River. The route they took probably led them across the Walla Walla River at a point near the mouth of Nine Mile Canyon, and then cross-country on a route roughly parallel to the current highway. On the Touchet River, they camped and waited for the return of Kelly and the rest of the Volunteers, who had proceeded in a northeasterly direction. They probably followed an old Indian trail that led from the mouth of the Walla Walla River to crossings of the Snake River to the north. The trail led to a steep descent into the canyon of the Touchet River, about 12 miles north of its mouth. At this location, a confrontation took place that would determine the course of the coming battle and place the great chief Peo-Peo-Mox Mox in the hands of the Oregon Volunteers.

As Kelly’s men entered the canyon, they were approached by a group of Indian warriors. Varying accounts place their number in a range of 50 to as many as 150. They had come from the main Walla Walla camp, located several miles farther up the Touchet River, beyond a narrow defile. Seven of the Indians separated themselves from the rest and rode toward the soldiers, holding forth a white flag of truce. Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox was recognized as he asked to speak with Indian Agent Nathan Olney. Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, Olney, and several others, including interpreter John McBean, rode to meet the chief, who expressed a wish for peace. When Kelly accused the chief of participating in the destruction and looting of Fort Walla Walla, Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox responded with regret and offered to replace or pay for stolen items. But Kelly demanded more than promises, insisting that the Walla Wallas in the camp ahead give up their weapons, feed the soldiers, and supply them with fresh horses. The chief assented and asked to be allowed to return to the main camp to arrange for compliance with the demands. Kelly, however, did not trust the chief, declaring that his men would fall upon the camp if he attempted to return.

Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox very likely felt he had no choice but to agree. He allowed the group of seven to be placed under guard. The chief invited the soldiers to go to the Walla Walla camp, promising to supply them with beef. The command moved forward, shadowed by 80 or so Indian warriors. As the canyon narrowed, the soldiers became fearful of ambush. Kelly’s intuition led him to order a retreat to a wider, more defensible position. He sent a messenger downstream to Major Chinn’s camp, requesting reinforcements. That evening, Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox asked permission to send one of his companions to the Walla Walla camp to make arrangements to comply with the terms of peace. Kelly relented and the man left. When he failed to return, the suspicions of the soldiers deepened.

The next morning, that of December 6, Lieutenant Colonel Kelly once again ordered his men toward the Walla Walla camp. When the soldiers reached it, they found it deserted. Mounted warriors watched from the surrounding heights, but they could not be persuaded to come forward. Finding that he could neither close with the Indian fighters, nor enforce the terms of his demands, Kelly turned his command around and headed back to the mouth of the Touchet River, where Major Chinn’s detachment waited. There, one of the Indians attempted to escape, but was dragged back. Kelly ordered the captives to be tied. He released them the next morning, but he then rebuked the chief, accusing him of going back on his promise and preventing an attack on the Indian camp before it could be abandoned. He threatened that if any other attempts at escape were made, he would order them all to be shot. Now the Indians were truly hostages.

From the camp on the Touchet River, Lieutenant Colonel Kelly planned to take his command up the Walla Walla valley to Waiilatpu, where Marcus Whitman’s mission once lay. Kelly was determined to make a more permanent camp there and hold out for the winter. He didn’t believe he would face a battle, thinking that the Indians on their faster ponies would simply out distance his men. The planned route would lead him to a crossing of Dry Creek. Beyond this lay pleasing agricultural land that had been settled mostly by French-Canadian former Hudson’s Bay Company employees and their Native American wives. The area was called Frenchtown or, simply, the French Farms. Wood fencing and occasional cabins marked the grassy landscape. Most of the inhabitants, however, had fled in the face of the rising tensions between the settlers and the Indians that had once befriended them. Now, a number of French-Canadians rode with the Oregon Volunteers.

The Battle Begins

On the morning of December 7, 1855, the Volunteers awoke to find mounted Indian warriors on the high ground east of the Touchet River, mostly Walla Wallas, but also including Cayuses, Umatillas, De Chutes, Palouses, and possibly elements of other groups. It is estimated that during the coming four-day battle, between 600 and 1,200 Indian fighters were involved, the smaller number probably being closest to the truth. Reportedly, some of the Indians shouted across the river, demanding the release of Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox and threatening to attack any soldiers who crossed the Touchet River. Regardless, two companies crossed the stream, followed by a third. Some accounts say that cattle drovers crossing the river to the north of the soldiers were fired upon by Indians. Others state that a soldier was the first to shoot. A fourth company crossed the river and the command surged forward, excepting two companies that held back to protect the baggage train and guard the Indian hostages.

The ensuing fight was a running battle. The soldiers became disorganized as the faster mounts outdistanced other slower horses. The Indians fought individually instead of in concerted groups, and they were proficient at shooting from horseback, whereas most of the soldiers had to dismount, fire, and resume pursuit. When the fight reached Dry Creek, near the present day town of Lowden, the soldiers were momentarily checked by Indians firing down upon them from a high knoll, and by fires set in the tall grass. But the knoll was flanked, and the soldiers pushed forward.

Beyond Dry Creek, the valley narrowed. The Indians made a stand at a French Canadian farm that had recently been abandoned by the La Rocque family. The soldiers had come about seven miles from their start at the Touchet River, and both the men and their horses were exhausted. The Indians held a line that stretched from the north bank of the Walla Walla River, where cover was provided by trees and underbrush, across the level gap where the La Rocque farm lay, and into the rolling hills to the north. In the flat, the Indians fired from the cover of sagebrush and sandy knolls. Those Volunteers on the fastest horses advanced on the farm, but were met by withering gunfire, and the soldiers fell back, many of them wounded.

What followed was later described by Lieutenant Colonel Kelly as the crucial moment of the entire four-day battle. He ordered his men to cross the fence of the farm and attack the defenders near the La Rocque cabin. The soldiers prevailed in the resulting assault and took possession of the cabin. But Lieutenant J. M. Burrows was killed, and others were wounded. The Indians conducted a fighting withdrawal.

The Indians made another stand about two miles farther up the valley, at another farm, marked by the Tellier cabin. Again, fences barred the soldier’s path. In the assault on the defending positions, Captain Charles Bennett and Private Kelso were killed. The Indians held their ground. In the midst of the fracas, Captain A. V. Wilson set up an old howitzer that he had hauled from Fort Walla Walla. It had no carriage, but he ordered his men to set it up on a mound of sand. The gun was fired successfully three times, with little effect. On the fourth try, it burst apart, severely injuring Captain Wilson. The Volunteers succeeded in occupying the Tellier farm, but abandoned their positions that night, withdrawing to the La Rocque farm, where barricades had been thrown up. The cabin was requisitioned for use as a field hospital and also served as the quarters for Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox and the other hostages.

The Killing of Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox

In the late afternoon of that day, December 7, 1855, an unfortunate incident occurred that would forever mark the battle with the dark brand of infamy. Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox and four of the other five hostages were killed. Lieutenant Colonel Kelly was present when the captives were brought to the cabin. The guards were worried that the prisoners might escape during the heat of battle. Kelly, feeling that every man might be needed in the fight, ordered the Indians to be tied. There are several versions of what happened next. Most agree that one of the Indians attempted an escape. Called by various names, including Klickitat Jim, Champoeg Jim, and Wolfskin, this man produced a hidden knife and swept it at Sergeant Major Isaac Miller. The attacker was quickly beaten with a rifle and left unconscious. At the same time as this action, Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox tried to take the rifle from Private Sam Warfield, who drew the weapon back, then struck the chief on the head, bending the barrel. Suddenly, other soldiers opened fire on the group of Indians, killing them all except for a young Nez Perce boy, Billy, who had begged for protection and was spared.

The killings were precipitated by fear and stress generated by the heated battle ranging around the cabin and the desperate escape attempt. The Indian victims were scalped, as was standard procedure. But the further mutilation of Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox’s body -- the removal of his ears and the flaying of his skin -- was inexcusable and even horrified some of the soldiers. Later, Lieutenant Colonel Kelly and other officers defended the actions of their men, although describing the matter as unfortunate.

Fighting Continues

There was no more fighting the night of December 7, the first day of battle. But the next morning, the soldiers again found themselves under heavy fire. Once again they advanced eastward toward the Tellier farm. Again, the Indians hid themselves in the brush along the river, in the sagebrush and sand knolls of the flat, and the hills to the north. As the soldiers advanced, they built rifle pits and other forms of cover. Private Flemming was mortally injured in the fight. Towards evening, the Volunteers again withdrew to the La Rocque farm.

The next morning, that of December 9, they saw that the Indians had occupied the defensive positions that the soldiers had constructed. The pattern of attack and withdrawal continued that day, but with seemingly diminished intensity. Supplies, especially ammunition, were running short. Kelly sent a messenger to Fort Henrietta, requesting immediate supply and reinforcements. The next day, December 10, the soldiers were near the breaking point when, at mid-day, smoke signals announced the approach of the relief column, led by Captain Tom Cornelius. His men arrived toward evening. The disheartened Indians withdrew and by the next day, December 11, they had vanished, fleeing with their families to temporary safety beyond the Snake River to the north.

Aftermath

Seven Oregon Mounted Volunteers died in the Battle of Walla Walla, and 13 were wounded. This seems to be a low number, but actually represented the higher end for battle casualties during interior Pacific Northwest hostilities. Indian deaths during the battle have been estimated at between 75 and 100. Only 39 bodies were counted on the field, but it was the Indian practice to take away their dead. The day after the battle concluded, December 11, Kelly ordered several detachments to pursue the Indians. At Mill Creek, about 12 miles beyond the former Whitman Mission site, the soldiers came across the deserted Walla Walla camp. Much in the way of provisions was discovered among 196 hastily abandoned campfires. The soldiers pressed forward as far as the upper Touchet River, finding no Walla Wallas.

But they were contacted by French Canadians and Indians who had chosen not to participate in the fight, and who requested protection from the soldiers. Many of them had gone eastward to seek sanctuary among the Nez Perce. The refugees were brought back to Mill Creek, where many of their possessions were looted by the soldiers. On December 15, Lieutenant Colonel Kelly abandoned the defenses at the La Rocque cabin, which had been named Fort Bennett, after the officer who was killed on the first day of battle. That place had become a muddy hole, reeking with the smell of dead men and animals. The new camp was established about two miles up Mill Creek from the old mission. This was Camp Curry. Its exact location has never been determined. The First Oregon Mounted Volunteers spent a dreary winter in the vicinity of Camp Curry. The next spring, they made an ineffective sweep through the lower Snake and mid Columbia river valleys, before returning to The Dalles. The unit was disbanded on June 1, 1856, and the men returned to their homes, mostly in western Oregon.

The next year, 1856, the Walla Walla Valley was occupied by large numbers of Federal troops. Among them were two officers, Colonel Edward Steptoe (1816-1865) and Colonel George Wright (1803-1865). Yakamas joined tribes to the east, including the Palouse, Spokane, and Coeur d’Alene, who formed a loose alliance to stop the oncoming whites. By 1858, Colonel Steptoe had established a new Fort Walla Walla, located near the current town of Walla Walla. That spring, Steptoe led a doomed expedition into the Palouse Hills north of the Snake River. At the Battle of Tohotonimme, near present day Rosalia, his men were attacked by overwhelming numbers of Indian warriors, who surrounded the soldiers, and then expelled them back beyond the Snake River.

Later that year, Colonel Wright led a much larger and better armed force into the Spokane and Coeur d’Alene lands, routing the warriors, destroying the Indians' infrastructure, and forcing peace agreements. On the way back to Fort Walla Walla, Wright’s command camped on the banks of Latah (Hangman) Creek. When several Indians were lured into the campsite, one of them -- Qualchan, son of Yakama Chief Owhi -- was cruelly hanged.

Native Americans of the inland Pacific Northwest would not again seriously threaten the whites with armed force until the Nez Perce campaign of 1877. As a result of the hostilities of 1855, the fortunes of the Walla Walla tribe collapsed. Previously, in 1854, Isaac Ingalls Stevens described them as diminished in numbers by disease (about 600) but nonetheless prosperous, owning large herds of horses and cattle. Chief Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox alone is said to have possessed at least a thousand head of livestock. In 1857, two years after the battle, the Walla Wallas are described as quite poor, their livestock reduced and scattered, and living on government assistance. By 1860, only about 50 remained near the mouth of the Walla Walla River. Most others had removed themselves to fishing stations near Priest Rapids, on the Columbia River. They had only a few horses and no cattle at all.