On October 27, 1855, Nisqually and Klickitat tribesmen battle Territorial Volunteers sent to seize Nisqually chiefs Leschi (1808-1858) and Quiemuth in Pierce County. Two volunteers die on October 29 (some sources say the date was October 27) and two more die Ocotober 31. These fights and the killing of white settlers on October 28 on the White River trigger the Indian War of 1855-1856 on the west side of the Cascade Mountains.

Hostilities

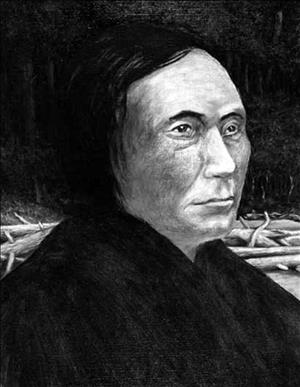

After the killings of eight miners and Indian Agent Andrew Jackson Bolon (d. 1855) by Yakama tribesmen in September 1855, Acting Territorial Governor Charles H. Mason (1830-1859) met with Chiefs Leschi and Quiemuth. Leschi was half-Yakama and retained close ties with the men now in open conflict with the U.S. Army. The Nisqually leaders repeated to Mason their unwillingness to move to the reservation assigned to them in the Medicine Creek Treaty of the prior December. The reservation lands were too small for them to support themselves and the chiefs already cultivated their own farms and pastures off the reservation.

After the meeting, James McAllister, a Medicine Creek settler since 1844, wrote to Mason and alleged that Leschi "has been doing all that he could possibly do to unite the Indians to raise against the whites in a hostile manner" (Wilkinson, 15).

Mason called for volunteers to join U.S. Army troops under Captain Maurice Maloney, 4th U.S. Infantry, in marching on the Yakama country. Mason also ordered the Mounted Rangers, a company of 18 men led by Captain Charles H. Eaton, to patrol the west side of the Cascades and "disarm any unusual or suspicious assemblage of Indians." Any who resisted should be put to death. Mason told Eaton that any Indians acting as emissaries "to incite the tribes now at peace to join the war party, you will hang" (Bonney, 175).

Mason wanted Eaton to seize Leschi and Quiemuth of the Nisquallys and the two brothers of chief Patkanim of the Snoqualmies. Seattle resident and community leader Arthur Denny (1822-1899) intervened on behalf of the Snoqualmies because he knew Patkanim and his tribe were not generally hostile and because Seattle needed Indians as laborers and mill workers.

Deadly Warfare

Eaton rode south to Mount St. Helens, then north into the Nisqually country. On October 25, Leschi and Quiemuth learned of Eaton's approach and they fled north to the Muckleshoot country. The volunteers helped themselves to the chiefs' horses and headed north after Leschi. Interpreting this and Captain Maloney's march on the Yakama country as hostile acts, warriors of several tribes gathered on the White River under Leschi's leadership.

On October 27, the Nisquallys moved against Eaton and they trapped him and 10 men in an abandoned cabin on the Puyallup River for 100 hours before the volunteers escaped. The next morning, October 28, on Leschi's orders, Muckleshoots and Klickitats attacked settlers along the White River, killing nine.

On October 29, Eaton sent Lieutenant James McAllister (the author of the letter to Governor Mason about Leschi) and settler Michael Connell to convince Leschi to not attack settlers. As they approached the Nisqually camp on Connell's Prairie, the Nisquallys killed the men, believing they were attacking.

On October 31, Leschi's men surrounded six riders from Maloney's command carrying messages across Connell's Prairie. Kitsap of the Klickitats (different from Kitsap of the Nisquallys and Suquamish) and Quiemuth promised friendship while the other warriors prepared an ambush. In the ensuing hand-to-hand combat, volunteers Benton Moses and Joseph Miles died. The other riders escaped.

Leschi had yet to unify the other tribes of Puget Sound and after the White River killings, the other Puget Sound tribes pulled back from his leadership and repaired to towns and reservations. Leschi's forces probably numbered fewer than 200 men made up of individuals from the Nisqually, Lower Puyallup, Upper Puyallup, Muckleshoot, Duwamish, Suquamish, Snoqualmie, and Klickitat tribes.

A monument erected by the Washington State Historical Society commemorates the 1855 killings on Connell's Prairie. In 2007 Connell's Prairie was occupied by small farms and ranches and suburban homes.