On Tuesday, August 6, 1974, a Burlington Northern Railway tank-car containing chemicals explodes in the Appleyard Terminal, South Wenatchee, Chelan County, Washington, killing two people and injuring 66 more. The blast demolishes buildings, destroys railroad cars, and hurls burning wreckage over a wide area, starting large grass fires in South and East Wenatchee. The damage to the rail yard, railroad equipment, and nearby vehicles, homes, and businesses in South Wenatchee is estimated to be well over $5 million. After an 18-month investigation, the National Transportation Safety Board will be unable to determine the cause of the explosion. The disaster leaves the experts completely baffled and at a loss about preventing similar incidents.

The Appleyard Terminal

Three tank-cars, owned by the Burlington Northern Railway (BNR), were en route from an E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company chemical plant in Biwabik, Minnesota, to the company’s explosives manufacturing facility in Dupont, Pierce County, Washington. The cars, double-walled with an inner stainless steel tank encased by a 10-inches of fiberglass insulation and an outer steel shell, each contained 10,000 gallons of PR-M (monomethylamine nitrate), the company’s designation for a sensitizing agent used to make Tovex, a new type of explosive gel used by the mining industry. The PR-M was shipped in an 85 percent aqueous solution, keeping the chemical stable and supposedly safe. The Department of Transportation (DOT) classified the product in solution as a “flammable solid,” whereas dry PR-M crystals were classified as a “Class A explosive,” the same as dynamite. DuPont had been shipping the semi-solid chemical, under a special permit issued by DOT’s Office of Hazardous Material, since 1968

At about 12:35 p.m. on Tuesday, August 6, 1974, a tremendous explosion ripped through BNR’s Appleyard Terminal in South Wenatchee, followed by a huge ball of fire and a large mushroom cloud. The blast left a crater in the middle of the rail yard 80 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 35 feet deep, and all but leveled an area a half-mile-wide. Pieces of steel, many quite large and heavy, were found more than a mile from the site. Burning debris, cast a full half-mile, started large grass fires in South Wenatchee and, across the Columbia River, in East Wenatchee. Electricity and telephone service in the surrounding area was disrupted for 20 minutes.

Rescue Workers Rush to the Scene

After the explosion, a huge column of dense yellow smoke rose from freight cars, burning in the rail yard. Off-duty police, and firefighters, as well as doctors, nurses, and ambulances, rushed to South Wenatchee without being called. Police barricaded the area and it was patrolled by armed Washington National Guard soldiers to prevent looting. Salvation Army and Red Cross teams responded to the area and established relief centers to serve food and drinks to the rescue workers and help disaster victims.

With the help of three U.S. Forest Service aircraft, dropping water and fire-retardant chemicals on the site, and some two dozen fire trucks and crews, responding from most of the surrounding fire districts, the conflagration was contained and soon brought under control. By 2:30 p.m., railroad crews were busy pulling undamaged freight cars, some containing hazardous and explosive materials, to safety. Once, firefighters were evacuated from the area until two tank-cars of ammonium nitrate, discovered close to the fire, were moved. Throughout the afternoon, fire crews continued to extinguish secondary fires, rail car by rail car. Some wrecked freight cars, now filled with rubble, were left smoldering throughout the night. The main line through the terminal had not been damaged extensively and was back in service early the following morning.

Three hours after the incident, railroad officials and emergency-response experts gained access into the site to determine what had exploded and to evaluate the damage. They were confronted by a collection of railroad cars, twisted and fused together by the blast and subsequent fire. After an exhaustive inventory, BNR officials determined that a tank-car containing chemicals, en route to Dupont, Washington, was the only one missing. The tank-car had arrived Tuesday morning, four hours before the blast, and had been sitting stationary on a siding in the yard for an hour. A BNR spokesman said: “We can’t locate this car so we’re pretty sure that’s the one that’s blown up” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer).

DuPont officials insisted that monomethylamine nitrate in solution was inert and could not have exploded spontaneously. The firm had been shipping approximately 18 tank-cars per year, for six years, to their explosives manufacturing facility without difficulty and maintained that switching operations in the rail yard would be unlikely to trigger an explosion. A DuPont spokesman said: “It would have taken a rather large charge of explosives. A blasting cap or rifle bullet would not be enough to detonate it” (

Seattle Post-Intelligencer)

.

The prevailing theory seemed to be that sabotage may have been responsible for the massive explosion. On Wednesday, August 7, 1974, some two dozen investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (BATF), and the BNR Police, plus other experts, descended upon the terminal to search for clues. Unfortunately, the most important evidence had been literally “blown to pieces.” The crater was empty, except for a set of axles found buried 25 feet below the bottom and small pieces of steel buried in the dirt. Undaunted, investigators set about gathering tank-car fragments and collecting soil samples, hoping an analysis of the evidence would indicate the cause of the explosion. They found more pieces of shrapnel imbedded in the wreckage of nearby freight cars, and scattered across the landscape in a one-mile radius. The biggest fragment investigators found measured 18 by 24 inches; hundreds of others ranged upward from two inches.

Victims and Damage

Remarkably, only two people died in the explosion: David Maurice Jones, age 28, a BNR switch foreman, who was hurled through the air and died from severe head injuries, and a male transient who was in the restroom of a nearby building when it was demolished. Jones was buried on Friday morning, August 9, 1974, at the Evergreen Cemetery in East Wenatchee. The unknown victim was subsequently identified by the FBI through fingerprints as Lindell Worth Messer, age 34, from Crawford, Alabama. He was buried, at BNR’s expense, in the Wenatchee City Cemetery.

Sixty-six people were seriously injured, most suffering lacerations from flying window glass, and taken to Deaconess and Rosewood Hospitals for treatment. Only six victims sustained injuries severe enough to require hospitalization. The most critically injured was Christian Hartelius, a Seattle semi-truck driver, who was traveling along S Wenatchee Avenue in front of the New Terminal Hotel when his rig was blown off the road. His driving partner, Jack Wright, told reporters the “truck seemed to explode around us.”

Wenatchee Fire Chief Glen Harris said: “It’s a marvel we didn’t lose more people. The fact that it was in the middle of the noon hour also accounted for there not being many people in the area” (The Wenatchee World).

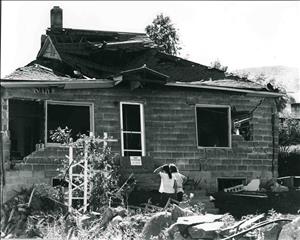

Washington State Insurance Commissioner Karl Herrmann estimated property damage at well over $5 million. Fifteen houses near the Appleyard Terminal were heavily damaged, and approximately 85 others had most of the windows broken. The concussion shattered glass in buildings, homes, and vehicles as far away as three-and-a-half miles. The Cedergreen Food Corporation, which operated a large cold-storage warehouse 150 yards from the site, lost approximately four million pounds of frozen vegetables when shrapnel ripped gaping holes into the side of the building, destroying the refrigeration system and filling the facility with ammonia and debris.

BNR officials said 71 freight cars near the blast site were destroyed and 101 others were damaged. In addition, six buildings inside the rail yard were demolished. A large disused roundhouse, less than 100 yards from the blast, absorbed the much of the concussion and protected many nearby homes from heavy damage. The rail yard was soon repaired and switching operations resumed within days of the disaster.

Investigating the Accident

On Monday, September 23, 1974, an NTSB board-of-inquiry began a week-long hearing, at the Thunderbird Motel in Wenatchee, to investigate the accident. Eye witnesses testified about what they had seen before the explosion and technical experts discussed every detail. Much of the testimony centered about federal requirements for shipping hazardous chemicals and whether the tank-car was in compliance. However none of the witnesses, including the FBI and BATF, had an inkling as to the cause of the blast. The last of 26 witnesses testified on Thursday evening and the hearing concluded on Friday, September 27, with a re-enactment of the switching activities, using the same crews and yard equipment. BNR crewmen had testified earlier the tank-car had been sitting idle on a sidetrack and nothing unusual had taken place.

The total cost of the disaster was approximately $10 million. The Federal government spent $1 million on the investigation. Not counting revenue, BNR lost $3.5 million in wrecked and damaged rolling stock, equipment, and buildings, and then spent at least $500,000 for cleanup, making repairs to the terminal and administrating damage claims. The railroad received some 1,700 claims for damages, amounting to approximately $5 million. One claim was from the Cedergreen Food Corporation, which sued BNR and DuPont in Federal court for $1.6 million in damages.

On February 2, 1976, the NTSB issued its final report, ending an 18-month investigation into the fatal accident. The report concluded that the board-of-inquiry was unable to determine the probable cause of the disaster and assigned no liability. The board issued five recommendations, however, urging the Department of Transportation to tighten shipping regulations for hazardous chemicals. The disaster left investigators and experts alike completely baffled and at a loss about preventing similar incidents.

Casualty List

Dead:

- David Maurice Jones, age 28, BNR switch foreman, East Wenatchee.

- Lindell Worth Messer, age 34, transient, Crawford, Alabama.

Injured:

- Lloyd Carlson, age 50, Wenatchee, head injury and severe lacerations.

- Mrs. Ruth Carlson, age 47, Wenatchee, multiple severe lacerations.

- Christian Hartelius, age 31, truck driver, Seattle, severe head and arm injuries.

- Peggy Mahoney, age 41, Wenatchee, head injury and severe lacerations.

- Mrs. Mae Murphy, age 38, Wenatchee, multiple severe lacerations.

-

Marvin Schultz, age 64, Wenatchee, punctured eardrum and severe lacerations.