On April 23, 2001, Douglas B. MacDonald (b. 1945), takes charge of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) as the state's fourth Secretary of Transportation. MacDonald, a Washington native who previously directed the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority, is credited with overseeing the cleanup of polluted Boston Harbor. He succeeds Sid Morrison (b. 1933), who has been Secretary since 1993. MacDonald will head WSDOT for six years, boosting WSDOT's public image and accountability and helping win passage of two major tax packages to fund transportation needs.

Raised in Washington

Doug MacDonald grew up on Mercer Island, graduating from Mercer Island High School in 1963. He earned undergraduate and law degrees from Harvard University sandwiched around a two-year stint with the Peace Corps in Africa. MacDonald practiced law in Chicago, then returned to the Boston area where he served as chief legal counsel to the Massachusetts Port Authority from 1975 to 1981.

After 11 years in private practice in Boston, MacDonald was appointed Executive Director of the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority in 1992. He headed the agency responsible for providing drinking water and wastewater treatment to some 60 Boston-area muncipalities for nine years, supervising a multibillion dollar effort to clean up the waters of Boston Harbor and developing a reputation as a hands-on manager and advocate for public accountability.

A Nonpolitical Secretary

When Sid Morrison announced he would retire after eight years as Transportation Secretary, the seven-member Washington State Transportation Commission conducted a nationwide search and selected MacDonald from a field of 26 candidates. (The Transportation Commission and its predecessor, the Highway Commission, had had ultimate authority over the state's transportation and highway system, including appointing the department head, since 1951.) MacDonald became the first Transportation Secretary in two decades who was not a politician -- Morrison was a former United States Representative and state legislator and Morrison's predecessor, Duane Berentson (1928-2013), was also a veteran state legislator.

As MacDonald took charge of WSDOT on April 23, 2001, the department faced considerable public and legislative skepticism as to its capabilities and performance, contributing to a reluctance to raise gas taxes. The lack of revenue in turn produced a growing backlog of unfunded transportation projects, which only got worse when a major earthquake struck western Washington on February 28, 2001, just days after MacDonald's appointment was announced.

Measuring and Managing

MacDonald moved quickly to improve, and demonstrate to the public, WSDOT's ability to deliver projects on time and on budget. He had the department establish and publicize quantifiable benchmarks for monitoring performance, saying "What gets measured, gets managed" (Moving Washington, 109). Under MacDonald, WSDOT won praise for candor by publishing quarterly Gray Notebooks that reported its performance on projects and programs through "Measures, Markers, and Mileposts" -- whether those benchmarks were met or missed. The department's website was acclaimed for its detailed project news and its real-time traffic information.

WSDOT's focus on accountability eventually paid dividends in the form of greater transportation funding through gas-tax increases. The Legislature had rejected increases in 2001 and in 2002 voters strongly rejected Referendum 51, which would have upped the gas tax by nine cents and raised other fees to fund $7.8 billion in transportation projects. However, in 2003, Democratic and Republican legislators agreed on a five-cent increase in the gas tax to fund priority "nickel projects" selected by the Legislature.

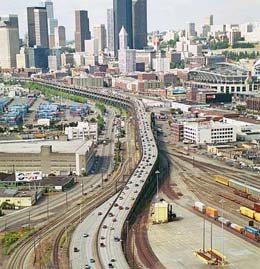

Two years later, with WSDOT making good progress on the "nickel projects," the Legislature approved a phased 9.5 cent gas-tax hike to fund an $8.5 billion transportation package, the largest in Washington history. Much of the funding was designated for replacing the aging and potentially unsafe Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle (damaged in the 2001 earthquake) and the SR 520 floating bridge across Lake Washington. The tax package survived an attempt to repeal it by initiative, with observers crediting MacDonald's leadership as a major factor in the somewhat unexpected defeat of Initiative 912.

Controversy and Achievement

The 2005 Legislature also restructured Washington's transportation leadership, reducing the role of the Transportation Commission and giving the governor direct authority to appoint the Secretary of Transportation. MacDonald, who was highly praised by legislators, stayed on under Governor Christine Gregoire for two years, but announced he would step down in July 2007.

MacDonald resigned without succeeding in finalizing either design or funding for the Alaskan Way Viaduct and 520 bridge replacements -- the state's two biggest and most controversial transportation projects during his six-year tenure. He became a central figure in the acrimonious debate over replacing the viaduct, asserting the department's position that a new elevated structure was the only viable option, while Seattle officials led by Mayor Greg Nickels (b. 1955) insisted on a tunnel.

The viaduct was not the only controversy MacDonald faced as Secretary. In December 2004, he canceled a massive graving dock project in Port Angeles, which was intended to build replacement sections for the Hood Canal Bridge and had already cost well over $50 million, when it became clear that the construction site was the location of Tse-whit-zen, an important Klallam village containing hundreds of intact human remains. Although many saw the episode as a low point for the department and MacDonald, the Secretary said that while he wished it had not occurred, "It was a hard experience to go through, but not unrewarding. Everyone learned through it and grew" (Gilmore). Frances Charles, chair of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe who had asked MacDonald to cancel the project, said, "We all had our differences but were always able to talk ... . It was very rare to have an individual like Secretary MacDonald really opening up his eyes and his heart" (Gilmore).

Despite the high profile setbacks, MacDonald achieved success on other major projects, most notably the new Tacoma Narrows Bridge, built for under the budgeted $800 million and scheduled to be dedicated before MacDonald's July 2007 departure from WSDOT.