This account of the mural of Seattle's Great Fire painted in 1953 by Rudolph Zallinger (1919-1995) was written by MOHAI historian Lorraine McConaghy, Ph.D. The fire occurred on June 6, 1889. The mural is on view in the main gallery at MOHAI (Museum of History & Industry), located in Seattle.

An Artist Is Born

One of Seattle’s most famous public artists immigrated to Washington state with his refugee family, fleeing revolutionary violence.

While serving in the Austrian army during World War I, Franz Zallinger was captured and imprisoned by the Russian army. In camp, Zallinger sketched prison life, and was eventually sent to Siberia to hand-paint china with the hammer-and-sickle design. There he fell in love with the daughter of a Polish engineer whom he met at the china factory, and the young couple married. In 1919, their son, Rudolph Zallinger, was born in Irkutsk, Siberia, and his parents soon escaped Soviet Russia to safe haven in Manchuria, where their daughter was born. After four years in Harbin, Franz Zallinger visited Seattle on the advice of the American consul in Manchuria, and then sent for the rest of his family to join him.

The refugees settled in Seattle in 1923, where Franz Zallinger found work as a professional decorator and artist. Rudolph Zallinger graduated from Queen Anne High School in 1937, and then won a scholarship to Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticut. While studying art at Yale, Zallinger earned pocket money drawing and painting seaweed to decorate gallery walls in the Peabody Museum of Natural History. The museum director noticed Zallinger’s meticulous draftsmanship and subtle use of color, and eventually commissioned the talented young artist to paint the major 110-foot mural for the Peabody’s gallery, “Age of Reptiles.” Zallinger’s prize-winning mural took four years to complete, and led to a Pulitzer arts scholarship.

After graduation, Rudolph Zallinger taught drawing and painting at Yale, and eventually was appointed assistant professor, remaining until 1950. He returned to Seattle with his own young family to open a portrait studio, assist his father with theatrical set decoration, and teach at the Burnley School of Professional Art, predecessor of today’s Art Institute of Seattle. Both Franz and Rudolph Zallinger painted murals in the Seattle area, often on hotel and restaurant walls -- some are now lost and others held in private and public collections.

Mural of the Great Fire

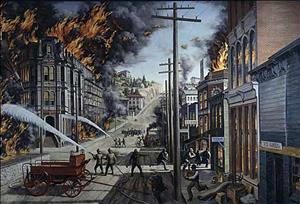

In 1953, the General Insurance Company of America, today’s SAFECO, commissioned Rudolph Zallinger to research and paint a mural for the Museum of History & Industry, depicting the Great Fire of 1889. The mural is 10 feet high by 24 feet wide and hangs today in the museum’s main gallery. In the painting, the artist’s perspective was from the intersection of Yesler Way, 1st Avenue, and James Street, in what is now Pioneer Square, looking east up steep Yesler Hill. The mural tells a dramatic story, capturing the moment when the fire escaped control, to consume Seattle. In the mural, an excited crowd has gathered up Yesler Way to watch the spectacle, as flames leap higher and higher, and burning debris fills the air.

The large building on the left, with its turret falling in flames, was the Yesler Block, and beyond it the Occidental Hotel. Shopkeepers rush from their stores, their arms full, trying to save their most valuable stock. Seattle’s volunteer firefighters bravely but hopelessly fight the fire, as water from their hoses cannot reach the roaring blaze. Zallinger researched historic photos to document every detail from buttons on the firemen’s uniforms to elements of urban architecture, but he was reduced to studying burning garbage in the old Montlake dump to capture the color and shape of the vivid flames.

Seattle’s Great Fire began on a hot, dry afternoon -- June 6, 1889 -- in a carpenter shop at 1st Avenue and Madison Street. A workman, John Back, was melting a cake of wood glue, and the hot glue boiled over onto the floor, igniting wood shavings and sawdust. Back threw a bucket of water on the little fire, which did not extinguish the flames but just distributed them more widely. Soon fire had consumed the room, driving Back out the door. Then flames swept out through the shop’s open doors and windows, and spread to adjacent buildings, leaping from roof to roof, igniting the wooden sidewalk and walls, the canvas signs and storage tents. A hot, dry breeze whipped the flames throughout the town, completely overwhelming firefighting efforts. Within 24 hours, the entire commercial heart of town from 3rd Avenue west to the wharves had burned to the ground -- a loss of about $10 million.

Remembering the Great Fire

When the Zallinger mural was unveiled in 1953, the Museum of History & Industry was less than two years old. Fifty surviving eyewitnesses of the Great Fire gathered to reminisce about that extraordinary day in 1889, for an audience of more than 100 interested visitors. Many of these memories were recorded in 1953 and the recording remains in the museum’s collection; other memories were published in Seattle’s newspapers. Henry Grant remembered, “A friend and I packed out load after load of candy from the store where he worked. Every time we came back to the vacant lot where we were putting the candy for safekeeping, the previous pile would be gone. Finally the store owner told us to forget the whole project and let the candy burn up!”

Another eyewitness responded to Grant, remembering that her brother went missing for hours on June 6, and the family frantically looked high and low for the little boy. She chuckled that he finally came home at 3 a.m. smelling of smoke but perfectly safe -- "with his pockets full of candy!"

J. T. Gilfillan remembered sitting at his desk in the Denny School when the town firebell began to ring; he and the class were writing their term-end examinations. As smoke drifted through the classroom’s open window, the excited class craned their necks to see what was happening, but their teacher said, “Now, just sit tight, boys, until you finish your examination papers; then you can go see what the fuss is all about.”

Dozens of men and women stood up to remember their experiences of the Fire.

Then the draperies were pulled away from the mural, revealing Zallinger’s dramatic imagining of one decisive moment on the afternoon of June 6, 1889, during the Great Fire that destroyed Seattle. The band burst into “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” and the visitors burst into applause.

In 1889, Seattle burned to the ground, clearing the way for change: The boomtown took the opportunity to reinvent itself as a cosmopolitan city with a proper building code and a professional fire department. Within weeks of the fire, Seattle exploded with new construction, booming with jobs and enthusiasm; within a year of the fire, the city’s population had grown by 6,000 residents to more than 37,000.

Rudolph Zallinger's Life and Art

Throughout the 1950s, Rudolph Zallinger shuttled between Connecticut and Seattle, teaching and painting, and working on a long series of Life covers and book illustrations depicting subjects in world history and the sciences. In the 1960s, he permanently relocated to a teaching post at the University of Hartford, and was appointed artist-in-residence at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, completing other murals, including the spectacular “Age of Mammals.” In 1980, Zallinger received the Verrill Award, which recognizes extraordinary contributions to science and natural history -- he was the first nonscientist to be so honored. The medal inscription reads:

"Rudolph Franz Zallinger, artist and teacher, your great natural history murals at the Peabody Museum are a fusion of scientific accuracy and artistic genius. Guided by your own diligent research and painstaking collaboration with scientists, your imagination has allowed us a glimpse into past worlds no human eye ever witnessed. It was your innovation to blend the static frames of successive geologic ages into grand panoramas that sweep through time, capturing the dynamic force of life as it evolved."

Rudolph Zallinger died in 1995 near his home in Connecticut, honored for his work in museums on both coasts, in bringing compelling images of science and history to the American public. Zallinger’s remarkable mural of Seattle’s Great Fire of 1889 is still on display at the Museum of History & Industry, a local work by this extraordinary artist, whose life traced a course from Siberia to Seattle, from refugee to artist.