On November 30, 1859, amidst the bustling trade of the “Golden Age of Sail,” a schooner called the Black Diamond is apprehended while docking at Port Townsend on return from Vancouver Island. After failing to register with the customs official and then refusing to provide license or paperwork, the ship is confiscated by the U.S. government. Eventually the case of the United States v. Schooner Black Diamond is brought to court, after which the Black Diamond is sold and her owners heavily fined.

The Coasting Trade

Schooner Black Diamond was licensed at the Custom House in Puget Sound on September 5, 1859 by the Collector, Morris H Frost. She was to be employed in the “Coasting Trade.” From the mid-nineteenth century, these boats, mainly schooners or windjammers, spent most of their time engaged in the “Coasting Trade.” This mainly entailed sailing up and down the West Coast of North America, bringing lumber from the Pacific Northwest to San Francisco or salmon from Alaska to California, along with the transport of other goods including coal, butter, sugar, and alcohol. A license for the coasting trade meant that the vessel was licensed to trade only within the United States.

The United States alleged that the ship had changed hands before the September 5 licensing date. The sale was not reported and no official notice of the new owner or master was made. The new master instead illegally sailed the Black Diamond under license granted to another man no longer involved with the boat.

Between November 1 and 29, 1859, the schooner went on “a foreign voyage and to a foreign port or place,” that is, to Victoria, British Columbia, "from a place within the collection district where she was licensed," that is, from Port Townsend. Before departing on the journey, the vessel's master had ignored the law and did not give up her license to the collector. The boat had left the United States without being registered by that collector.

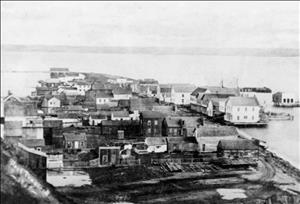

The Black Diamond arrived at Port Townsend from Victoria, Vancouver Island, on November 29, 1859. James M. Selden, U.S. Revenue Collector at Port Townsend, witnessed the arrival of the ship, but after no man came to him to register her arrival, he approached and boarded the schooner “at some time between nine and ten p.m.” Selden demanded a conference with the ship’s master and presentation of the schooner’s license.

The prosecution alleged that though a Mr. Dwyer introduced himself as Master, Selden’s request for the license was refused and “said master did not exhibit the same.” Instead, the Black Diamond remained at the Port Townsend dock “for more than twenty-four hours after arriving” and within that time period the master never went to the Office of the Collector to officially report the arrival of the boat, thereby violating United States law.

Black Diamond Seized

On November 30, 1859, Morris H. Frost, the Collector of Customs for the Collection District of Puget Sound, seized the Black Diamond and everything on board -- “her tackle, apparel, and furniture” -- and held them in custody as liable to be proceeded against for libel. At the time of the seizure, Frost talked to the same man that Revenue Collector Selden had spoken to the night before. In court, Frost recalled that “Mr. Dwyer said he was master at the time it was seized” and “he said he had made two trips to Victoria and back. This being illegal under the license given on 5 September, I asked him if he had ever had any description or paper, such as a clearance -- he said he had not.”

On December 5, 1859, a "libel of information" was filed in the District Court of the United States, Third Judicial District in and for the territory of Washington regarding United States v. Schooner Black Diamond. The trial of the case began in Port Townsend at 8 a.m. on January 5, 1860. It was presided over by the Honorable E. C. Fitzhugh, Judge of the District Court of the United States. In an effort to discredit the prosecution’s claim that the ship docked illegally and without registering on the 29th of November, large portions of the first day’s deliberations were devoted to arguments over whether the degree of light afforded by the dusk on the evening of the 29th was sufficient to obscure a ship coming into port or not, and quibbles over exactly how far away one could accurately see at 10 p.m. at the end of November.

The proceedings went on for several days, and the prosecution took the upper hand with clear evidence of illegal activity. Collector Morris Frost testified that “no application has been made for a license for [the Black Diamond] to proceed to or take in a foreign port,” yet master Dwyer “said he had made two trips to Victoria and back.” Evidence backing Morris up is strong -- a Victoria newspaper’s records list the schooner’s arrival on Vancouver Island. On February 20, 1860, new allegations were added to the libel of information in the case by acting U.S. District Attorney B. F. Davison. On top of the previous assertions, the prosecution alleged that though the Black Diamond was “licensed for the, “coasting trade” ... after the Claimant, Brownsfield, became owner, [she] was employed in a trade other than that of which she was licensed, to wit, in the “foreign trade.” Because of this engagement in trade outside of the United States, “she, together with her tackle, apparel, and furniture became forfeited to the United States.”

Further additions to the case against the Black Diamond included the refusal of Mr. Dwyer to give the ship’s license to Collector Selden and the failure of the new master (Dwyer) and new owner (Brownfield) to register the sale and change of master of the schooner.

With regards to the new developments, Morris Frost noted that the current owner of the schooner denied the boat’s ever having been sold, testifying that “I had some conversation with Brownfield on the morning of the 30th. He informed me that he was the owner of the Schooner Black Diamond and always had been.” It was harder to refute the allegations of unregistered change of master -- the license granted was to “the Schooner called the Black Diamond whereof the said Daniel Howell is Master,” while “Mr. Dwyer said he was master at the time it was seized.” W. H. Taylor told the court, “I have continued since that time [of licensing] to act as Deputy Collector. That license has never been surrendered nor returned for any purpose to my knowledge,” showing a clear violation of the U.S. statute requiring new or updated licenses for ships under new masters. On March 3, 1860, final sentencing in the case took place. Judge Fitzhugh sided with the prosecution. He ordered the sale of the schooner and everything on board as well as fine of over $300 for the irresponsible owner and master.

On March 19, 1860, the Black Diamond was sold along with her tackle, apparel, and furniture, for the total sum of $700. It was an unhappy ending for the disgraced and heavily fined Dwyer, who announces that “he was the man on board when papers were demanded and if he had known as much then as he did now he would have shot the first man that put his foot on deck.”