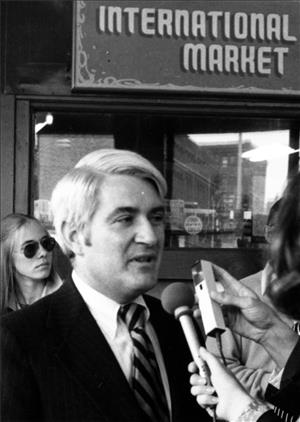

Seattle mayor Wes Uhlman proposes that the city establish a Division on Aging, one of the nation’s first. The agency will be part of the city’s new Office of Human Resources and will coordinate programs that benefit the city’s 75,000 elderly citizens, many of whom live in substandard housing and struggle to pay their bills.

They Pay Their Taxes

“These thousands of senior citizens don’t march on City Hall or sit in or picket any more,” Uhlman said as he announced the new program. “They just pay their taxes --and have done so all their lives” (The Seattle Times, April 4, 1971).

In May 1971, the City Council approved Uhlman’s plan and made Morton L. Schwabacher, who had been the president of the Seattle-King County Council on Aging, the office’s first director. During its first year, the Division on Aging tried to draw the attention of the city’s public agencies to the needs of its elderly. It compiled a directory of senior-citizen services, did a study of the city’s nursing homes, and encouraged older people to present a “united front of senior power.”

Most importantly, though, the agency tackled employment discrimination -- it worked with the city’s Women’s Division to add “sex” and “age” to Seattle’s Fair Employment Practices guidelines -- and tried to make public transit more accessible to older and disabled riders by lowering fares and adding handrails and easier-to-climb steps to city buses.

Expanding to King County

In 1973, the Division on Aging became the Area Agency on Aging for all of King County. The new agency had more money and a more comprehensive mission: to provide nutritious food, legal services, transportation, and home health care to elderly people who needed it in Seattle and King County. That same year, the city implemented a 20 percent taxi-fare discount for elderly riders. By 1975, the agency was sponsoring social events, day trips, and neighborhood health clinics and Senior Citizen Centers along with a low-cost handyman service and Minor Home Repair Program. Two years later, the mayor issued an Executive Order, the first of its kind in the United States, abolishing mandatory retirement for city workers.

In the early 1980s, the Agency on Aging ran into a bit of trouble: Because many of the agency’s administrators were not senior citizens themselves, the Seattle Gray Panthers accused the agency of discrimination. The situation, the Panthers charged, was “like a women’s commission composed only of men, or a racial discrimination agency run by whites” (Seattle P-I, November 7, 1980). In response to the Panthers’ criticism, the city agreed to add more elderly people to the agency’s roster of policymakers and staff.

Today (2007), in addition to funding many of the advocacy, and elder-support programs that Uhlman envisioned more than two decades ago, the Area Agency on Aging for Seattle and King County promotes healthy aging for all by encouraging older people to eat well (by sponsoring community meals and distributing fresh produce) and stay active.