Port Angeles, the county seat of Clallam County since 1890, is built on the site of two major Klallam villages, I'e'nis and Tse-whit-zen, on the north shore of the Olympic Peninsula. It sits on a natural harbor, named Puerto de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles by Spanish mariners, that is protected by the long sand spit of Ediz Hook jutting into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Founded in 1862, a few years after the first handful of American settlers took up residence among the Klallam villagers, Port Angeles grew slowly until the late 1880s, when the booming economy and the arrival of the utopian Puget Sound Co-operative Colony drew an influx of settlers. In 1890 the city incorporated and won the Clallam County seat, positioning it as the county's civic, commercial, and industrial center. The primary industry was processing the harvest from the massive old growth forests that stretched south and west from Port Angeles in the foothills of the Olympic range. For most of the twentieth century large lumber, pulp, paper, and plywood mills along the city's waterfront powered the economy. In recent years the economy has diversified. With Olympic National Park's headquarters in the city and major attractions nearby, tourism is particularly important.

Tse-whit-zen and I'e'nis

Ediz Hook and the bay it protects are near the center of traditional Klallam territory, which extended along the Strait of Juan de Fuca from the Hoko River in the west to beyond Discovery Bay in the east. The sheltered harbor, a prime location, has been inhabited for more than 2,700 years. For at least 400 years, two major Klallam villages shared the harbor area. I'e'nis was located on the east side, at the mouth of a salmon stream now called Ennis Creek -- both the creek and Ediz Hook derive their names from "I'e'nis," reported to mean "good beach." In the mid to late 1800s, I'e'nis was fortified with a double stockade and was variously reported to have 200 to 1,500 residents.

Tse-whit-zen was farther west, near the lagoon at the base of Ediz Hook. Archeological investigation in 2004 documented six longhouses in the village, along with a stockade similar to that observed at I'e'nis. Near Tse-whit-zen was a large cemetery, probably the burial place for a number of villages. With burial canoes hung from trees or from scaffolds erected for the purpose and decorated with blankets and other possessions, the cemetery was a prominent feature into the late 1800s.

Explorers and Settlers

Like all villages in the area, Tse-whit-zen and I'e'nis were regularly visited by members of other tribal communities from Puget Sound, the Pacific coast, Vancouver Island, and even farther afield. The first non-Indians reached the villages in 1791. Spanish naval vessels San Carlos and the Santa Saturnina, on an exploring expedition headed by Francisco de Eliza, entered the deep harbor that Eliza named Puerto de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles.

British Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798) followed the Spanish a year later. He shortened and anglicized the name Eliza gave the harbor to its present form. Even before the explorers reached them, the villagers had been decimated by European diseases. However, the Klallam remained the Port Angeles area's only inhabitants for another 60 years.

The first American settlers at Port Angeles were Angus Johnson, Alexander Sampson, Rufus Holmes and William Winsor, although accounts differ as to who arrived first and whether that first arrival came in 1856 or 1857. None brought families -- Sampson was separated from his wife and the others were bachelors. The men staked Donation Land Act claims near the Klallam villages. Sampson located his claim in the cemetery near Tse-whit-zen and residents resisted his intrusion until he worked out an agreement with a local leader that allowed him to build a home on the condition that he not disturb the graves.

The Cherbourg Land Company

A handful of additional settlers arrived over the next few years. In 1859 several of the newer arrivals joined with Sampson, Holmes, and Winsor to form the Cherbourg Land Company to plat a town site and sell lots, despite the fact that by law their donation land claims were only for settlement, not re-sale. The company's name was inspired by Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), former governor of Washington Territory and at the time its Congressional delegate, who foresaw Port Angeles harbor as an important American navy base, dubbing it a "Cherbourg of the Pacific" (Martin, 14). (Cherbourg was a French seaport where Louis XIV established a fortified naval base.)

Somehow the Cherbourg Land Company caught the attention of Victor Smith (1827-1865), a protégé of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873). It appears that Smith, and perhaps Chase too, invested in the Cherbourg Land Company and land claims in Port Angeles before Smith first set foot in Washington Territory. As they were doing so, Chase appointed Smith Collector of Customs for the Puget Sound District.

From the time, in 1861, he arrived in Port Townsend, Jefferson County, then the Customs Port of Entry, Smith began agitating to move the Port of Entry to "Cherbourg" or Port Angeles, where he continued to acquire interests in land. In 1862, he won passage of congressional legislation transferring the Port of Entry.

Smith's grandiose plans involved more than the Customs House. With Chase's support, he succeeded in getting President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) to designate 3,520 acres at Port Angeles as a federal reserve for lighthouse, military, and naval purposes. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers platted a federal townsite on the reserve land, laying out the street plan (patterned after Victor Smith's former home town of Cincinnati, Ohio) which still exists today. The fact that Washington, D.C., was the only other city officially laid out by the federal government led the U.S. Board of Trade in 1890 to dub Port Angeles the "Second National City."

Even before the townsite was officially established, Smith, his wife Caroline, and their four children moved to Port Angeles, apparently the first non-Indian family to settle there. Numerous relatives came with them. Samuel Stork, married to one of Victor Smith's sisters, established a trading post at Port Angeles in 1861 along with Smith's brother Henry. Victor's father, George Smith, served as keeper at Tatoosh Lighthouse off Cape Flattery and became the first keeper of the Ediz Hook lighthouse when it opened in 1865.

Victor Smith died in the July 30, 1865, shipwreck of the Brother Jonathan, and for a while it looked like the city he founded would perish too. Even before his death, when federal townsite lots were offered for sale in 1864 they found few takers. In 1866, Port Townsend interests reclaimed the Port of Entry. As the Custom House departed, so did many of the new settlers.

A City Arises

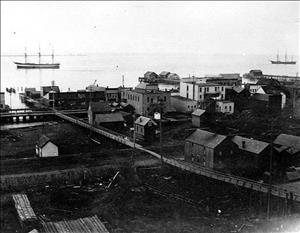

Not until the mid 1880s -- a boom time throughout Washington Territory -- did Port Angeles see permanent commercial development. In 1883 and 1884 Eben Gay Morse built a hotel and his son-in-law David W. Morse, who had taken over Stork's trading post, expanded it into the first general store. David Morse also built the first wharf, at the location of the current ferry pier. These developments began attracting newcomers to build homes nearby.

However, it was the Puget Sound Co-operative Colony that was most responsible for the subsequent expansion of Port Angeles. The Colony purchased land a short distance east of the existing Port Angeles settlement, on Ennis Creek opposite the village of I'e'nis. Colonists began arriving in late 1886 and by the next summer the population of the Colony rivaled that of the existing town. Despite, or to some extent because of its success in attracting adherents, the Puget Sound Co-operative Colony did not last long as an experiment in collective living. Within a few years, it evolved into more of an entrepreneurial enterprise. The commercial ventures ultimately failed, factional disputes generated lawsuits, and the Colony was forced into receivership.

Even as the Colony faded, Port Angeles continued to flourish, due in no small part to the influx of idealistic and energetic settlers who arrived as Colonists. A village of a few hundred in 1886, Port Angeles had over 3,000 residents by 1890. In June of that year, voters held a town meeting and officially incorporated the City of Port Angeles. The following month, settlers frustrated that the bulk of the 3,520-acre federal reserve remained off limits, "jumped the Reserve." Squatters moved en masse onto the federal land, laid claim to two lots each, and mounted a lobbying campaign that paid off with 1891 legislation officially opening the reserve to homesteading.

With its growth spurt, Port Angeles had become the largest population center in Clallam County, outpacing the small community of New Dungeness (at the base of Dungeness Spit near present-day Sequim) that was then the county seat. Rival promoters of Port Angeles and Port Crescent, at the time a booming logging community located west of Port Angeles on Crescent Bay, succeeded in having the location of the county seat put to a vote in the November 1890 election. Port Angeles easily out-polled its two rivals, solidifying its position as the civic, commercial, and industrial center of Clallam County.

The city's growth slowed as a result of the nationwide depression dubbed the Panic of 1893. Some residents left as land and timber prices plummeted. A sawmill run by the Filion brothers, who were among a group of Civil War veterans who arrived in 1892, provided one of the few sources of income in town. Currency was scarce after the city's only bank failed in June 1893. Gregers M. Lauridsen, a leading businessman, filled the gap by issuing his own money. Technically good only for merchandise at Lauridsen's store, the "Lauridsen Money" or "Port Angeles Money" circulated all over the Olympic Peninsula as the equivalent of U.S. currency for 10 years, helping Port Angeles and the surrounding region through the economic hard times.

Making Improvements

The regional economy improved as logging of the Olympic Peninsula's massive conifer forests intensified in the early years of the twentieth century. By 1914, Port Angeles was in the midst of multiple civic improvement projects. Construction began on a permanent County Courthouse to replace the succession of temporary quarters used since Port Angeles became the county seat a quarter century earlier.

A massive regrading project used water to wash away hills that impeded downtown streets. The dirt was used to raise Front Street, along the waterfront, and nearby streets some 12 feet to lift them above the tides that often used to inundate them with salt water (and city sewage). Storeowners raised their buildings well above the foundations to meet the new street level.

Three more developments celebrated at a February 1914 banquet -- construction of a large sawmill and arrival of a railroad and hydropower -- were key to solidifying Port Angeles's position as the industrial center where products from the surrounding forests were processed. Hydroelectric power from a dam on the Elwha River, the brainchild of real-estate developer Thomas T. Aldwell (1868-1954), who spent 20 years acquiring the land and arranging for financing and construction of the dam, first arrived in Port Angeles in December 1913.

From at least the 1880s, citizens of Port Angeles, like those of virtually every settlement in Washington, had sought a railroad connection, and for more than 30 years numerous promoters had promised a line without anything getting built. Finally in 1912 two Seattle-based businessmen, logging baron Michael Earles (d. 1919) and contractor C. J. Erickson, toured the immense timber stands west of Port Angeles and came to an agreement: Earles would build a major sawmill at Port Angeles if Erickson would build a railroad from the city to the timber. By the summer of 1914, Earles had completed the "Big Mill" at the base of Ediz Hook and the rail line Erickson constructed was supplying the mill with logs. The Big Mill was the city's largest industrial plant until it closed during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The Pulp Industry

After World War I, during which electricity from Thomas Aldwell's dam powered the Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, the Elwha hydropower put Port Angeles at the forefront of the pulp and paper industry, which grew rapidly in the 1920s as forestry research chemists developed techniques for processing western hemlock and other pulpwoods into paper or cellulose. Aldwell played a leading role in enticing mills to the city to use the Elwha electricity. He convinced A. H. Dougall to locate a boxboard mill producing cartons and paper packaging on a portion of Alexander Sampson's former land claim where Tse-whit-zen and its cemetery had been located. The mill began production in 1918 as the Crescent Boxboard Company and was later named Fibreboard Products.

In 1919, Aldwell invited the Zellerbach Paper Company of San Francisco to invest in a planned pulp mill at Ediz Hook next to the Crescent Boxboard site. Operating first under the name Washington Pulp and Paper Corporation, and later for many years as Crown Zellerbach, the company began production newsprint and paper at the Port Angeles pulp mill in 1921. During construction of the mill in 1920, "hundreds of Indian bones were disturbed" (Lewarch, 21), a fact widely reported at the time but largely forgotten over the years.

A third major Port Angeles pulp mill began production in 1930. It was located at the Ennis Creek site that had belonged to the Puget Sound Co-operative Colony. During World War I, the U.S. Army Spruce Production Division built a spruce mill there but the war ended before the mill was put to use. In 1929, the Olympic Forest Products Company dismantled most of the spruce mill and reconstructed in its place a pulp mill, which was subsequently operated for many years by Rayonier.

Depression and New Deal

Coming just as the country plunged into the Great Depression, the large demolition and construction project for the Olympic Forest Products mill helped Port Angeles stave off the effects of the Depression for more than a year by keeping many local workers employed. But by the early 1930s, jobs and money were scarce in Port Angeles as they were everywhere.

New Deal agencies and programs established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1881-1945) to combat the economic hard times provided much-needed jobs and helped to build institutions that continue to play important roles in the economic and civic life of Port Angeles. Beginning in 1934, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), working with the Army and Navy, developed an airport just west of downtown. Home to a fighter squadron during World War II, after the war, the airport became the Clallam County Municipal Landing Field. The Port of Port Angeles took over operations in 1951 and the facility was later named the William R. Fairchild International Airport.

The WPA also built the headquarters for the Coast Guard Air Station -- the first on the Pacific Coast -- commissioned at Ediz Hook in 1935. The Coast Guard base forced a second relocation of Klallam families originally from Tse-whit-zen who had moved out onto the spit as mills were built over their old village location. The federal government moved them to land along the Elwha River west of the city, which later became the Lower Elwha Klallam Reservation. Congress created Olympic National Park in the mountains south of Port Angeles in 1938, and park headquarters were built on Peabody Heights in Port Angeles, in the first time a national park headquarters was located outside park boundaries.

Although the New Deal programs helped, it was the economic stimulus of World War II that finally ended the Depression. Even before the U.S. entered the war, demand for all kinds of forestry products was soaring, among them plywood. In the first decades of the twentieth century, researchers developed improved glues (first from skim milk, then from soybeans) to hold separate wood sheets together and devised ways to make the resulting plywood waterproof. Many plywood mills using the new techniques were built as cooperatives, with workers investing together to own the plant. In 1941, 272 members opened the cooperative Peninsula Plywood Company on the center of the Port Angeles waterfront to help meet the wartime demand for plywood.

Mills and More

The four major mills built along the Port Angeles waterfront between 1920 and 1941-- Crown Zellerbach, Fibreboard, Peninsula Plywood, and Rayonier -- remained the backbone of the city's economy in the post-war years. Tourism became increasingly important as the growing national affluence, and especially the 1961 opening of the Hood Canal Bridge that cut driving time from the populated central Puget Sound region, brought more visitors drawn by the mountains, rivers, and rainforest of Olympic National Park and by fishing and boating along the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Rising freight costs, both for bringing raw materials ever-increasing distances and for shipping the finished product, led the Fibreboard mill to close permanently on the last day of 1970. Logging declined rapidly in Clallam County after the 1980s, with most of the large timber gone and stricter environmental regulations in place. The Rayonier mill closed in 1997.

The other two mills remained among the top private employers in Port Angeles as of 2007, although both had seen changes in ownership. The pulp mill at Ediz Hook passed from Crown Zellerbach to Daishowa America and then to Nippon Paper Industries. The cooperative plywood mill was worker-run for 30 years until the owners sold it to ITT in 1971. It was bought by Klukwan, Inc., an Alaskan Native village corporation in 1989, and is now known as K Ply.

Other industrial jobs replaced some of those lost as mills closed, including at Westport Shipyard building motor yachts and at Angeles Composite Technologies manufacturing airplane parts, but service jobs climbed as a percentage of private sector employment. The largest payrolls in the city belonged to government institutions, including not just the city and county, but also to hospitals, schools, and federal agencies such as the National Park Service and Coast Guard. Port Angeles continued to grow at a steady rate, with its 2005 population estimated at 18,640.

By the start of the twenty-first century, Port Angeles may have appeared to retain virtually no trace of the Klallam villages that had occupied the harbor little more than 150 years earlier, but such appearances were deceiving. The cultural and human remains of Tse-whit-zen, which were well-known but disregarded when mills were built over them in the 1920s, were apparently unknown but soon very much regarded when the state Department of Transportation chose Port Angeles in 2002 as the site of a graving dock project. Construction stopped shortly after it began in 2003 when it human remains and artifacts were unearthed. Subsequent archeological investigation revealed virtually the entire village of Tse-whit-zen and multiple burials, leading to relocation of the graving dock and new insight into life on Port Angeles harbor in the hundreds of years before Victor Smith plotted a town site there.