This essay on Seattle's Potlatch, the Ad Club, and Seattle's Potlatch Bug is based on materials found in the library of Seattle's Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI). It was prepared by MOHAI historian Lorraine McConaghy, Ph.D.

Seattle's Potlatch Bug

Seattle’s Potlatch was first organized in 1911 to celebrate the city’s booming prosperity and capitalize on the popularity of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Potlatch was the brainchild of Seattle’s biggest downtown promoters: the Chamber of Commerce, both major newspapers, the Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times, and the brand-new Seattle Advertising Club.

The Ad Club’s slogan to hype the Potlatch was “Organized Optimism,” and the zealous young ad men energetically praised the festival’s boosters and ridiculed any slackers or detractors as “knockers.” As the Potlatch copy put it, the 1912 celebration would “chase the village pessimist out into the never-never and establish a perennial parade of optimists on Second Avenue.”

Optimist Joseph Blethen was the eldest son of Seattle Times publisher Alden Blethen and the president of the Ad Club, which had organized specifically to work on the Potlatch. In 1912, Joe Blethen was also elected president of the Potlatch, and his father chaired the Seattle Chamber of Commerce Bureau of Publicity.

The two men worked hard to make the Potlatch a public relations triumph for Seattle. The Ad Club frankly staged the Potlatch as “an advertising stunt,” as Joe Blethen put it, to assert Seattle’s character as the emerging metropolis of the Pacific Northwest, north to Alaska. The Seattle Times cooperated fully, publishing almost daily press releases, poetry, news, songs, and images generated at a dizzying pace by the Potlatch planners.

Joseph Blethen was the author of a number of 1912 booster ditties, including "The Potlatch’s Coming!" of which the chorus ran,

Go and get a Puget sound on,

That’s the kind of noise to pound on --

Go and get a Puget sound on,

For the Potlatch Nine-teen-twelve.

Seattle’s Potlatch stitched together the jarringly dissimilar themes of the Gold Rush, U.S. Navy militarism, and down-home summer fun, merging the three under a very loose adaptation of the Native American potlatch celebration. Organizers explained that they had borrowed the term “potlatch” from the “quaint jargon of the Chinook,” meaning a “carnival of sports, music, dancing and feasting, and the distributing of gifts by the hosts to all the guests.”

Organizers developed an extended Indian fantasy to suggest the exotic and mysterious character of the Potlatch. The Tillikums of Elttaes formed a local “secret order,” affecting to dress as Indians and greeting newcomers as well as one another with “Klahowya,” or “welcome” in Chinook. The narrative that shaped the Potlatch festival was that the Hyas Tyee, the “chief of the North,” paddled to Seattle to visit “his white brethren of the South.” He was attended by leaders of five Alaskan tribes, each represented by a contrived totem, the “grotesquely carved expression of the family tree.” The Hyas Tyee shared his knowledge of the “picturesque and romantic” Indian north with Potlatch visitors, and in return, the city of Seattle offered him access to “the ways of modernity.”

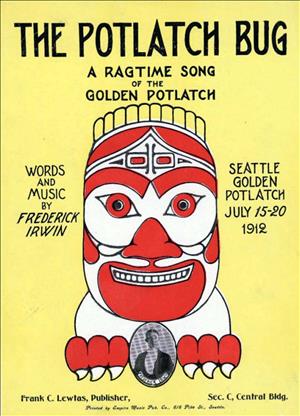

In the Seattle Potlatch myth, the five Alaskan tribal groups -- all, of course, Seattle businessmen in costume -- were responsible for constructing floats to lead the Great Potlatch Parade. So the tribe of Ikht, of the bear totem, built an electrically lit float describing life on the lake, while the Moxt tribe depicted life in the air, with the raven as its totem, and the Klone tribe, of the whale totem, built a float describing life on the water. While the Hyas Tyee and his attendants remained in town, Seattle was decorated with 250 plaster totem poles which bore the same exaggerated features as the Potlatch Bug.

The Bug was the festival’s ubiquitous emblem: a “grotesque from a totem pole,” as the Ad Club put it, “[that] grins and grins and grins, yet always with good nature.” The Bug was produced as an automobile emblem, made of enameled brass, and as a lapel pin, identifying the wearer as a Potlatch Booster. The Bug image appeared on stationery, posters, postcards, and banners -- even on local candy and coffee labels.

The “microbe of optimism” was infectious, intended to “inoculate you with the carnival spirit” and encourage local involvement and hard work: raising money, building floats, organizing parades, and publicizing the upcoming festival. The Bug was formally introduced to fraternal and service organizations around town in special programs presented by Ad Club members. For instance, at a smoker for Seattle’s Elks Lodge 92, Potlatch organizers offered an evening of theater and song, jokingly warning Lodge members: “Any [Elks] member found with Bug Exterminator or Insect Powder on his person, will be quietly ejected from the hall.”

Under the rubric, “Get the Bug,” members of Seattle’s Knights of Columbus were encouraged to meet the Bug High Priest for initiation “into the mysteries of the ancient and honorable order of Potlatch Bugs.” The initiation was a mock injection of “the Sacred Virus of the Great Bug,” administered by an Ad Club member who attended the meeting in full regalia. The Advertising Club’s dramatic troupe wrote and presented the programs that introduced the Bug to gatherings around town. Members, including Joseph Blethen, performed in plays entitled “The Latest Ideas in Bugs” and “The Bug and His Family Tree” throughout the winter and spring of 1912, building excitement for that year's Potlatch. Members of local clubs as widely diverse as the Arctic Club and the Oddfellows gamely sang along, to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy”:

The Bug

The Potlatch Bug’s a fearful thing,

Beyond imagination.

When once it plants its venomed sting

It means inoculation.

The symptoms well are known to all

And so, too, what its bite is,

The aftermath, the doctors call

Enthusiasmitis.

There is no further use to fight

A prophylactic battle;

The Potlatch Bug is sure to bite

Each booster in Seattle.

As enthusiasmitis swept Seattle, the Bug’s grinning face seemed to be everywhere. After the resounding success of the 1912 Potlatch, planning immediately began for 1913, for the Golden Potlatch. The Bug remained the Potlatch emblem. For instance, the Bug visited clubs in Everett to invite everyone to the Golden Potlatch, and its cutting-edge “electrical pageant”:

"Its four days of fast and furious fun will open ... with the gorgeous electrical pageant of the Tilikums [sic]. Every hour of the day and night, until its close, will be full of action, weird and colorful, and every feature will be free. You can’t afford to miss the entertainment that your big sister — Seattle — has prepared. It will be just as welcome to you as the cool sea breezes that waft up over Puget Sound ... Seattle owes you a good time. Come and take it."

The 1913 Potlatch didn’t turn out to be a very “good time,” as a violent and destructive riot swept the city after the parade. But the Potlatch Bug and the adapted Native American iconography that it represents reflect an interesting period in Seattle’s urban history, when the bustling, modernizing city sought to characterize its summer festival with misappropriated Indian motifs, seen as romantic, exotic, picturesque, and distinctly Northwest.