On March 23, 1900, Rose Brooks was one of 50 working women who gathered under the dynamic leadership of 23-year-old Alice Lord (1877-1940) to found Seattle’s Waitresses’ Union, Local 240, of the Hotel and Restaurant Employees’ International Alliance. This account of Rose Brooks and her union is based on the Rose Brooks collection (2006.41), located in the archives of Seattle's Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI) and donated by Brooks’s niece, Patricia Brooks Greetham. It was prepared by MOHAI historian Lorraine McConaghy, Ph.D.

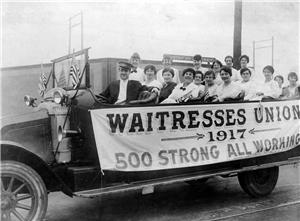

The Seattle Waitresses’ Union was the first chartered waitresses-only local in the United States, and represented more than 200 Seattle waitresses by 1902.

When Brooks and the other charter members organized to form their local, Seattle was exploding with growth, in the midst of the decade-long Gold Rush to the north. Ten thousand hopeful miners pulsed through the city each year, and they outfitted, lodged, and boarded in Seattle: local waitresses worked 14-hour days, seven days a week, for a weekly wage of between $5 and $7.

Alice Lord arrived in Seattle in about 1899, as a young woman of 22 and set about earning her living as a waitress; within the year, charismatic “Sister Lord” had recruited the charter members of Local 240. The men of organized labor wondered whether the women would be successful. Alice Lord proudly responded in the craft periodical, Mixer and Server, in January 1906:

"I believe there should be a waitresses’ local in every city whose population is large enough to demand such. In a mixed local, the girls do not take the interest that they should; they always leave the work to the boys ... . but if the girls know that the success of the local depends on their efforts, they will put their shoulders to the wheel ... ."

Active, caring and militant, the Waitresses’ Union lobbied and crusaded for their own members, but also for all women workers. They gained the 10-hour-work day for Washington state women workers in 1910 and the eight-hour day the following year. Local 240 struck successfully for a six-day work week for Seattle waitresses in 1907. But surely their greatest triumph was the 1913 passage of a minimum wage for women in Washington. Alice Lord wrote of their success:

"A good many people thought an organization run by girls would not last long. But you see, the girls belong to a race whose forefathers fought for the liberty of humanity in 1861-1865 (during the Civil War), and they are fighters, too — this time, for the liberty of the wage earner."

Listed as Rosa Brooks in the 1900 Seattle City Directory, Brooks worked in the Brooks Brothers Restaurant; three years later, in 1903, she was listed as a “waiter,” resided downtown at 1009 3rd Avenue, and worked at the Levi Brooks Restaurant, at 1420 3rd Avenue. A charter member of Local 240, “Sister Brooks” was a member of a close-knit group of female friends and co-workers, who gathered together for weekly suppers of beer and crab, and lots of talk.

Rose Brooks’ 1903 Working Card was signed by Augusta Blase, and showed her dues paid through July of that year. Membership in the union permitted Rose to receive union benefits and representation, and to vote for officers. In 1907, Rose Brooks requested a withdrawal card, which identified her as a member in good standing of the Waitresses’ Union, and exempted her for a time from paying dues. Both Eva Mae Callum and Alice Lord’s signatures are at the bottom of the document, with the local’s address noted as the Labor Temple, at 6th and University. In 1910 Lord also signed a dues receipt for Brooks that noted her purchase of a Waitresses’ Union button.

Documents in the file indicate that the Waitresses’ Union met every Friday at 6:30 p.m. in the Labor Temple, and that dues were 75 cents per month. Rose Brooks’s 1905 membership book included the union constitution and general rules, with the prologue:

"We declare that labor creates all wealth, but the laborer does not receive his due share of the wealth he produces; therefore, to enable him to secure his full rights, he must unite with his fellow-workers so as to accomplish by united action what is impossible by individual effort ... ."

"Recognizing the fact that organization is necessary for the amelioration and final emancipation of labor, we have organized the Hotel and Restaurant Employees’ International Alliance."

The general rules required members to either be citizens or to become naturalized.

They required locals to accept “colored worker at our craft” if a “colored local” did not exist in the city. In Seattle, the Waitresses’ Union was a whites-only local, and flouted this regulation.

A local could request a charter from the International if there were more than 10 members -- in fact, if more than 10 bartenders, cooks, or waiters accumulated in a general local, they were required to apply for a new local charter for their own craft.

The local was required to seek sanction of the General Executive Board for any strike, “to the end that strikes may be less frequent and more effective,” though provision was made for unauthorized strikes if a local was willing to strike “entirely upon its own resources and risk.”

The union’s benefits were of great importance to members who were adrift from their families or who feared indigence in their old age. The Hotel and Restaurant Employees’ locals paid a death benefit of between $50 and $100 to members, and each local assumed the responsibility of arranging a suitable burial for members who have “no known relatives or friends.”