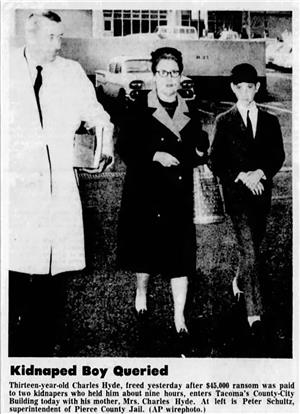

On November 17, 1965, three men kidnap Charles H. Hyde III, age 13, from a school bus stop in Lakewood, near Tacoma (Pierce County) in broad daylight. His captors telephone the Hyde family, demanding $45,000 for the boy's safe return. His father, Charles H. Hyde II acts immediately and pays the ransom. Young Charles is released nine hours later in an empty building on Ruston Way near Tacoma's Old Town Dock. On November 20, 1965, Tilford G. Baker, age 34, surrenders to the Pierce County Sheriff's Department, confesses to the crime and implicates two accomplices. Federal fugitive warrants are immediately issued for Dean A. Bromley, age 20, and James E. Evans, age 31. That night the FBI captures Bromley in Arkansas. Two days later, on November 22, Evans, who had fled to California, returns to Tacoma and surrenders. The men, pleading insanity, go to trial in February 1966 and are found guilty. Baker is a given life sentence for first-degree kidnapping and Evans 10 years for conspiracy to kidnap. Bromley will appeal and the Washington State Supreme Court will grant him a new trial. But the result is the same and he will be sentenced to life in prison. The Hyde family usually shunned publicity, but the kidnapping of young Charles gained national attention and became one of the most sensational regional crime stories of the decade.

Charles Is Kidnapped

At 7:45 a.m. on Wednesday, November 17, 1965, 13-year-old Charles Henry Hyde III, a eighth-grade student at the Charles Wright Academy, located at 7723 Chambers Creek Road W, University Place, was walking from his home located at 12745 Gravelly Lake Drive SW, Lakewood, toward a nearby school-bus stop when a white four-door sedan pulled up beside him and stopped. A man, wearing a yellow and blue Madras-plaid hat and dark glasses, exited the passenger side of car and began asking Charles questions. Suddenly he grabbed Charles by the arm and pulled him into the vehicle, saying they were giving him a ride to school. Charles was forced to lie on the floor in the back seat of the car, his eyelids were taped shut, and he was covered with a blanket.

At about 9:30 a.m., the kidnappers stopped at a house, wrapped up Charles in a tarp and carried him inside. They placed a telephone call to his father, Charles Henry Hyde II (1914-1998), president of the West Coast Grocery Company, 1525 E “D” Street, the largest grocery wholesaler in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, established by the Hyde family in 1891. The kidnapers told Mr. Hyde his son was being held for ransom and then ordered Charles to say hello to his father. They instructed Mr. Hyde to buy a black valise for $4.95 at the Eagle Loan Company, a pawn shop, at S 15th Street and Pacific Avenue, withdraw $45,000 from his bank in old, unmarked $5, $10, $20, and $100 bills, drive to the pay-telephone booth in front of the Signal service station at S 72nd Street and S Park Avenue in South Tacoma by 3:00 p.m. and wait for a phone call with further instructions.

After obtaining the black valise, Mr. Hyde went to the Bank of California and, without offering an explanation, withdrew the ransom money from his business account and drove to the phone booth. The pay phone rang at 3:00 p.m. and the kidnapers instructed Mr. Hyde to drive to the Park-N-Shop supermarket at S 96th Street and Pacific Avenue in Parkland, some two miles away. He was told to park in the alley behind the market, leave his car unlocked with the money on the front seat, go to the phone booth at the front of the store and wait for another phone call with further instructions.

Mr. Hyde did as instructed and waited at the booth for approximately 10 minutes, but when no instructions came, he returned to his car found he had locked the doors. He unlocked the front doors and went back to the booth to wait for another 20 minutes, but when no call came, he went back to his car and found the valise containing the ransom money was gone. Mr. Hyde drove home, told his wife, Otis, what had happened, and contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

The FBI informed Mr. Hyde, since state lines had evidently not been crossed, they had no immediate jurisdiction and notified the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department, which had jurisdiction under state law. Within a short period of time, FBI agents and Sheriff’s officers arrived at the Hyde residence to learn the details of the crime, start an investigation and coordinate a statewide manhunt for the kidnappers. (A clause in the Federal Kidnapping Act, also known as the Lindbergh Law, enables the FBI to enter a case after 24 hours when it is presumed state lines have been crossed, making it a federal felony. The law was a response to the New Jersey kidnapping and murder in March 1932 of the 2-year-old son of Charles Lindbergh, the famous aviator, and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh.)

Charles Comes Home

Just after 7:00 p.m., Mr. Hyde received a telephone call from an attorney and family friend, Rush E. Stouffer, 605 N 8th Street, Tacoma, advising him that Charles was there, claiming he had been kidnapped and needed to call his father. Coincidentally, the Stoufer residence was across the street from the Tacoma Lawn Tennis Club where George H. Weyerhaeuser was kidnapped in 1935. The Hydes, accompanied by Pierce County Sheriff Jack Berry, arrived soon after to take Charles to Sheriff’s headquarters where he provided a detailed description of his captors and the kidnap car for a police bulletin.

The following morning, Charles recounted the details of his abduction for Sheriff Berry and the investigators. He said there were two kidnappers, both white males, and provided detailed descriptions. They had kept him under a blanket or blindfolded most of the time and, other than a 10-minute stop at a house to telephone his father with a demand for ransom, they stayed in the car and kept moving throughout the day. Once it got dark, about 5:30 p.m., the kidnappers left Charles in an abandoned brick building on Ruston Way near the Top of the Ocean Restaurant (later destroyed by fire in April 1977), adjacent to Tacoma’s Old Town Dock. They taped his wrists together and his eyes and mouth shut and told him to stay quiet for at least 30 minutes or he would be shot. The kidnappers told Charles to wait there for his father to pick him up. After freeing himself, Charles waited for a half-an-hour or so, then left the building. The area was familiar, so he headed across the railroad tracks, walked up the hill through Old Tacoma to the Stouffer residence and asked to use their telephone to call his parents.

Seeking the Kidnappers

Sheriff Berry conceded there were few clues to follow in the kidnapping and, through the news media, asked for help from the public to solve the case. Four people who witnessed the abduction told detectives there were two white males in a white, late-model compact car. One man, who thought the circumstances were suspicious, said the car was a white 1965 Plymouth Valiant four-door sedan. He followed the car for a short distance and jotted down the license plate number, BEM-942. Unfortunately, the license plate had been reported stolen prior to the incident and belonged on a 1955 Pontiac.

A Western Union clerk reported that a man telephoned their Tacoma office at 2:00 a.m. on Thursday, November 18, wanting to send a telegram to the Hyde residence disclosing where Charles had been released. When the clerk asked for the sender’s name, he abruptly hung up.

Tilford Baker Turns Himself In

Late Friday night, on November 19, Tilford Gerald Baker, 34, suffering from paroxysms of regret, confessed to his wife, Anna, that he had abducted young Charles Hyde and hidden most of the ransom money. Then he telephoned his parents, Ollie and Ruby Baker, and told them the same story. After talking things over with his family, Baker decided to seek redemption by turning himself in.

Baker, accompanied by his step-father, Ollie Baker, and his brother, Ronald, arrived at the Pierce County Sheriff’s Office at 3:45 a.m. on Saturday, November 20, 1965. He told the dispatcher he had information that could help solve the Hyde kidnapping. Baker was referred to Deputy David Larson and his partner, Lowell Johnson, who had been temporarily assigned to the detective division to assist on the Hyde investigation. After hearing his brief confession, Deputy Larson placed Baker under arrest and telephoned Sheriff Berry and Chief Criminal Deputy George V. Janovich with the news. Ironically, detectives had received three substantial leads during night, all pointing to Baker, and planned to pick him up Saturday morning for questioning.

Sheriff Berry and Chief Janovich rushed to the office to question Baker and obtain a formal confession. In his 22-page statement, Baker, an unemployed carpenter, said he masterminded the kidnapping and implicated two accomplices: Dean Allen Bromley, 20, an unemployed laborer, and James Edward Evans, 31, an unemployed mechanic. Baker conceived the idea while doing carpentry work at the house next door to the Hyde residence, which coincidentally belonged to Charles’s grandparents, Robert H. and Beulah L. Hyde. He sent Bromley and Evans to obtain a car for the abduction from Budget Rent-A-Car at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. Bromley attached a set of stolen license plates and drove the kidnap car. Baker snatched Charles off the street and held him captive in the back seat. After obtaining the ransom and freeing Charles, the trio decided to disperse. Evans flew to California to visit his brother in Hayward and gamble at Lake Tahoe; Bromley flew to Arkansas with his wife to visit relatives; Baker stayed in his house at 337 S 100th Street, Parkland, became remorseful and surrendered himself.

Baker told Sheriff Berry that most of the ransom money was hidden in a locker at the Santa Fair Lanes, a bowling alley located in the Federal Way Shopping Center, Pacific Highway S (State Route 99) and S 312th Street, and provided him the key. Inside the locker, detectives found a red plaid bowling-ball bag containing $34,360, mostly in bills of small denomination. The split was supposed to be $15,000 apiece, but the kidnappers decided to stash most of the money and divide it later, after the heat died down. Baker had given $6,500 to Bromley and $3,500 to Evans for traveling expenses and spent $640 on new clothes and partying.

At 1:00 p.m. on Saturday, Baker and an attorney hired by his family, Albert R. Malanca, appeared before Justice Court Judge Elizabeth Shackleford. Pierce County Chief Deputy Prosecutor Schuyler Jerome Witt filed a criminal complaint charging Baker, Bromley, and Evans with first-degree kidnapping. Baker, the father of two children, was described by his attorney as a good family man who came from a nice family and had never been in trouble. Judge Shackleford initially set bail at $25,000 but, because kidnapping is a capital crime, raised it later to $50,000 at the prosecutor’s request.

Evans and Bromley

When Assistant U.S. Attorney Charles W. Billinghurst learned that James Evans and Dean Bromley had fled the state, he filed federal fugitive warrants with U.S. Commissioner Robert E. Cooper, charging unlawful flight to avoid prosecution. Now there was federal jurisdiction, and the FBI could officially act. At 8:00 p.m. on Saturday night, FBI agents arrested Dean A. Bromley in a tavern in McCrory, Arkansas. He was with his pregnant, 17-year-old wife, Pauline, and in possession of $5,532. At his initial appearance in Little Rock, U.S. Commissioner John E. Coats set Bromley’s bail at $100,000 and ordered him held in the Polaski County jail until extradition papers arrived from the Pierce County Prosecutor’s office in Tacoma.

Coincidentally, on Saturday evening, Detective Captain Ernest Keck, Pierce County Sheriff’s Department, received a telephone call at home from James E. Evans, who said he was at Lake Tahoe, had heard the police were looking for him, and offered to return to Tacoma and surrender. Evans, who had left his pregnant wife, Dovie Jane, and four children in Tacoma, promised to notify Captain Keck as soon as he arrived.

At 1:45 a.m., on Monday, November 22, 1965, James Evans called Captain Keck, saying he was at his residence at 4524 E “C” Street. Captain Keck and Sheriff Berry took him into custody at 3:00 a.m., along with $2,260 of the ransom money. At his initial appearance in Justice Court, Evans was charged with first-degree kidnapping and Judge Shackleford set bail at $100,000.

At the Pierce County jail, Evans gave Sheriff Berry a four-page statement, outlining his role in the kidnapping. He said Baker gave him $25 to rent a vehicle for the kidnapping, but he had not been involved in the actual abduction. After receiving $3,500 for travel expenses, Evans flew to California, used $300 to purchase an old car and lost the rest of the missing money gambling in Lake Tahoe casinos. Evans, whose family had been on welfare for seven months, said his motive for participating in the scheme was easy money to pay mounting debts.

Pierce County Sheriff’s Detective William Regan brought Bromley back from Arkansas late Thursday night, November 25. At his initial appearance in Justice Court on Friday morning, Prosecutor Witt charged him with first-degree kidnapping and Judge Shackleford set bail at $100,000. A preliminary hearing had been set for all three defendants for December 6, but that date was vacated when Pierce County Prosecutor John G. McCutcheon filed the kidnapping case in Superior Court the following Monday. (Guilty pleas are not accepted in capital cases where the death penalty may be imposed.)

The Trial

The trial of the three kidnappers commenced on Monday, February 14, 1966, in Pierce County Superior Court, Tacoma, before Judge John D. Cochran. Although the defendants had pleaded not guilty at the arraignment, their attorneys filed motions to change the pleas to not guilty by reason of insanity. The prosecution team consisted of Pierce County Prosecutor McCutcheon, Chief Deputy Prosecutor Witt and Deputy Prosecutor Everett Plumb. Questioning of the prospective jurors revolved around their impressions of the crime gained from the news media and their views about an insanity defense and the death penalty. On Wednesday morning, after two days of questioning, a jury of four women and eight men plus two alternates was selected and sworn in.

Opening statements and testimony commenced on Wednesday, February 16. The prosecution stated simply that the defendant had kidnapped Charles H. Hyde III for monetary gain, were caught and confessed to the crime. They acted rationally and with purpose. The defense attorneys maintained the men were insane at the time of the kidnapping and didn’t know right from wrong.

The trial testimony lasted two weeks. The prosecution rested its case on Friday afternoon, February 18, after less than three days of direct testimony. By lottery, Tilford Baker had been selected to present his case first, followed by James Evans and then Dean Bromley.

The defense called Baker’s stepfather who testified about Tilford’s troubled childhood. Two expert witnesses, one psychiatrist and one psychologist, testified that Tilford was a psychotic schizophrenic, couldn’t tell right from wrong, and could have organic brain damage. Then Baker took the stand and, with his eyes tightly shut and his left hand beating a constant tattoo on the witness box, recounted the details of the kidnapping. When asked on cross examination if he was insane, Baker jumped up and shouted “Absolutely not!”

Evans did not take the stand to testify in his defense. His attorneys relied exclusively on testimony from family and friends that he was “dumb” and psychiatric testimony that he was a mental defective with an IQ of 65. A psychiatrist testified that although Evans basically knew the difference between right and wrong, he didn’t understand the gravity of the crime. He said Baker had become a father-figure whom Evans was trying to please and he was easily led astray.

In a surprising turn of events, Bromley changed his plea from “not guilty by reason of insanity” to a simple “not guilty.” Bromley took the stand and testified about his role in the kidnapping, but maintained that Baker, the insane mastermind, and Evans, his faithful companion, forced him to participate. He said that Baker had pulled a gun, terrifying him, and made him drive the kidnap car. On cross-examination, the prosecution pointed out that when Bromley initially confessed to the kidnapping, he never mentioned coercion or a gun. He also told Pierce County Deputy Sheriff Frank A. Peskin that, if not for Baker, it would have been the perfect crime and he should have killed Baker and Evans and taken all the money and gone to Brazil. Bromley had bragged how he planned to go to Eastern State Hospital and, after release, return to Tacoma and commit the perfect crime.

Closing arguments began on Monday, February 27. In his summation, Prosecutor Witt pointed to the cleverness with which the kidnapping was conceived and executed as proof that none of the defendants was mentally irresponsible and that all knew right from wrong. He ridiculed Baker’s histrionic testimony on the witness stand and asked why Evans fled to California after the kidnapping if he didn’t know he had done something wrong. Witt maintained that Bromley, a convicted burglar, was not afraid of Baker as the defense maintained and had ample opportunities to quit the conspiracy. Witnesses for Baker testified that he was harmless and couldn’t kill animals or bugs, implying that Charles, much less Bromley, was never in any danger. Attorneys for the defense, in their closing argument, maintained the accused were too insane, too stupid or too frightened to be responsible for their actions.

The trial concluded on Monday afternoon, and the case went to the jury at 5:15 p.m. After electing a foreman and going to dinner, the jury began deliberations at 8:30 p.m. and at 11:05 p.m. Bailiff Conney Nelson told Judge Cochran they had reached a verdict. Court was reconvened and the jury foreman, Ernest L. Fisher, announced that Baker and Bromley were found guilty of first-degree kidnapping, and Evans guilty of a lesser included offense, conspiracy to kidnap. Since the jury did not recommend the death penalty, Baker and Bromley faced mandatory sentences of “not more than life” in prison. (Life sentences in Washington usually run about 13 ½ years although the state parole board may review the prisoner’s sentence after seven-and-a-half years.) For Evans, the maximum sentence for conspiracy to kidnap was 10 years.

On Monday, March 10, 1966, Judge Cochran sentenced Baker to life and Evans to the maximum 10 years imprisonment. Bromley’s attorney, Robert Ray Briggs, filed a motion for a new trial, which was argued on Tuesday, March 22. The motion was subsequently denied and Bromley was sentenced to life imprisonment. On Thursday, March 24, Attorney Briggs filed an appeal to the Washington State Supreme Court, contesting Judge Cochran’s ruling. Neither Baker nor Evans appealed their sentences. The three prisoners were sent to the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla to begin serving their sentences.

Bromley's New Trial

On October 5, 1967, the State Supreme Court set aside Bromley’s conviction and granted him a new trial despite the fact that he had confessed to the kidnapping under oath in open court. The main issue the justices agreed upon was that the trial court had erred by permitting a state psychiatrist to testify in rebuttal that Bromley was not a person who could be easily coerced. Having withdrawn his insanity plea during trial, coercion was his only defense and the psychiatrist’s expert opinion could have unfairly prejudiced the jury.

Bromley’s second trial commenced on Monday, May 20, 1968, in Pierce County Superior Court, Tacoma, before Judge William L. Brown Jr. The entire trial lasted one week and the result was the same. On Saturday, May 25, after deliberating for six hours, the jury of eight women and four men found Bromley guilty of first-degree kidnapping and voted against the imposing the death penalty. The following day, he was returned to the Washington State Penitentiary to resume serving his mandatory life sentence. On July 12, Bromley appealed again to the Washington State Supreme Court for new trial based on Judge Brown’s admission in the retrial of his confession and incriminating statements, but the justices affirmed the Superior Court ruling on November 20, 1969.

Epilogue

James E. Evans was paroled from the Washington State Penitentiary in 1970, after serving four years of his 10 year sentence. He died in Seattle on died August 28, 1977, at age 43. Tilford G. Baker and Dean A. Bromley were paroled in 1975, after serving almost 10 years of their “not more than life” sentences. Bromley died in Tacoma on May 1, 1981, at age 35. Tilford Baker spent approximately 10 years on supervised parole, living in the greater Tacoma area, then dropped out of sight.