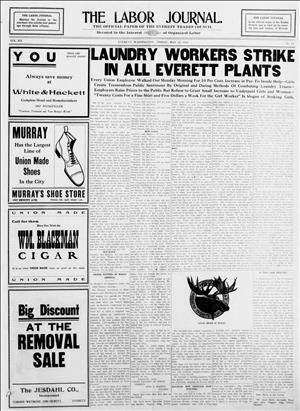

On May 23, 1910, Everett laundry employees – using the slogan "Twenty Cents for a Shirt and Five Dollars a Week for a Girl Worker" -- strike for an increase in pay. While laundry prices have increased, managers blaming rising labor costs, workers claim they have not received a pay raise in two years. No Everett laundry in 1910 recognizes the Laundry Workers Union, Local 154, but individual employees are union members and all risk losing their jobs by participating in the walkout. Strikers will work closely with union organizers and use the press effectively to build public support for their cause. The battle between managers and workers will quickly reach a boiling point, laundry owners planning to hire strike breakers, but workers win their demands in less than a week.

Claim Unfair Wages

Laundries were big business at the turn of the twentieth century, gaining work not only from individual households but from hotels, hospitals, barber shops, cafes, and other business establishments. Commercial laundries reached their peak in the 1920s, then slackened when home washing machines became affordable.

In 1910, luxury apartment house were beginning to add laundries for every tenant in their buildings. This included washing machines, irons and ironing boards, driers, and rollers, but these conveniences were available to a wealthy few and likely not as yet in Everett.

Workers in the early laundries were employed in various jobs. They were Markers and Sorters, Washers, Polishers (of equipment), Mangle Operators, Starchers, Machine and Hand Ironers, and Wagon Drivers. Laundresses jobs were difficult and the pay was low. Working the mangle presses was dangerous if the state-mandated safety guards were not in place and work hours fluctuated. Sometimes workers did not have enough hours and at other times they were required to work 10 or more hours a day.

Laundresses (the inside workers) were women while the wagon drivers were men. The few men who worked indoors were paid more than women doing the same jobs and this likely accounted for the reason laundries employed mostly women, whose wages were considered supplemental family income. Reported wages at the time of the strike show the disparity between genders. For those working as 1st Class Sorters and Markers, men received $18 a week compared to a woman’s pay of $12 a week. Men Washers received $18 a week, women $14; Starchers, men $18 week, women 17 cents an hour. Men were hired to run the central machines and to drive the delivery trucks.

Coordinated Strategy

Laundry owners planned to hire strike breakers but were outmaneuvered by coordination between laundry workers, laundry wagon drivers, and the union. They successfully rallied public support through newspaper stories and word-of-mouth. Although laundry wagon drivers were not officially on strike, they walked out in support of the women, and, with women workers aboard, they drove the streets of Everett, handmade banners flying, collecting dirty laundry. Two women reportedly drove wagons themselves. Customers also brought their dirty laundry to the Everett Labor Temple, where it was then trucked to Seattle’s Independent Laundry, which was a union shop. The cleaned and ironed laundry was then returned to the Labor Temple, where it was boxed and made ready for pickup or delivery.

Both sides held firmly, employers claiming they were not given any advanced warning of a walkout. They believed they could continue to operate with small crews of the non-union workers. Strikers showed a letter that was sent days before the strike, giving managers notice. A few days into the bargaining, employers were ready to agree on the wage increase but would not at first allow strikers to return to work.

An Everett Daily Herald reporter covering the story visited the Labor Temple and was met by a pile of soiled linen that the laundresses were sorting, marking, and preparing to send to Seattle for washing and ironing. One laundress there said, "Give up our strike? Well, I guess not!," a sentiment shared by other striking laundresses. "Wait a minute," she continued, "There’s the telephone bell. We are receiving so many calls from residences, hotels and restaurants to call and collect laundry that it keeps us on the jump; why we have more laundry here than all the laundries in town combined. The laundries will have to give in for the simple reason that they have little or no work" ("Both Sides …").

The strategy worked. Without dirty linen to clean – particularly specialty collars and cuffs – the plants had no work. A Labor Journal story was clear:

"The amount of work given to the girls in their whirlwind campaign surprised even them and made them go some to handle it all. Everybody wanted to give them their work and for about a week the Labor Temple looked like a big laundry. Soiled linen and clean liners, shipping boxes and crates, filled the office until there wasn’t room to take a long breath. Oh, there was something doing in the laundry business alright. Now that it is over, the Labor Temple force are willing to confess that they don’t contemplate entering the laundry profession as a regular occupation. No, thanks" ("Laundry Girls …").

The strike ran from a Monday to a Saturday. Terms of the settlement included a 10 percent increase for all inside workers and a promise that every striker wishing to work would be reinstated. The new wage scale was to be in effect for two years.

1910, A Good Year for Women

It is not surprising that the laundry strikers were able to raise considerable public support in a short time for their cause. Clearly they were underpaid, particularly the women. And in 1910 Washington voters were already highly organized and actively working for passage of Washington’s Women’s Suffrage Act, a bill that men voters approved in November 1910. The Everett Women’s Suffrage Club had its office in the Commerce Building on Hewitt Avenue, only a few blocks from two of the laundries. It was also a strong time for union strength in Everett. With this organizational structure in place, it was easy to rally public support for the laundry strikers.

A year later, this same coordinated effort helped to pass the Washington Women’s Eight-hour Work Day bill, HB 12, authored by State Representative John E. Campbell (1880-1924) of Everett.

Other battles were to be won, the Labor Journal writing: "There are girls in other occupations that work as hard and probably receive as little remuneration and half the public don’t know anything about it. The same desire for better working conditions and the same latent possibilities for them are present" ("Laundry Girls Win ...").