On August 20, 1953, one prisoner is killed and three are wounded by guard's gunfire when a riot breaks out at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe (Snohomish County). The shots are fired when a mob of inmates rush the prison gate. The rioters retreat but go on a rampage, breaking windows and wrecking machinery, setting fire to five buildings and destroying the interiors of the cell blocks. The turmoil will last for more than 36 hours before all the inmates are finally returned to their cells. The damage to the reformatory will total more than $750,000. It is the worst riot in the history of the Washington State Reformatory.

Monroe State Reformatory

The Washington State Reformatory, opened in 1910, is located in Monroe, approximately 20 miles east of Everett. Now called the Washington State Reformatory Unit (WSRU), it is part of the Monroe Correctional Complex which comprises four separate "units" with a total population of 2,500 male inmates and custody levels ranging from maximum to minimum. The WSRU houses up to 875 inmates in two large cell blocks that are the most prominent feature of this historical building. The 11-acre compound is surrounded by 30-foot-high red brick wall with six guard towers strategically placed to monitor activity inside the compound.

In August 1953, Paul J. Squier, age 57, was the reformatory supervisor. He had held the position for only 18 months, having arrived from the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in April 1952 where he had been employed for 30 years, the last 12 years as warden. Squier immediately put certain reforms into effect and spent $100,000 to enlarge the rehabilitation facilities and improve living conditions for the inmates. However, his efforts were being frustrated by a few of the staff seeking to undermine his authority and by the deep-seated unrest in the prison population, brought about by years of alleged corruption and abuse at the institution.

The Riot Begins

After dinner on Tuesday evening, August 20, 1953, most of the 615 inmates at the reformatory were in the yard inside the stockade, enjoying their daily recreational period. At 7:00 p.m., Corrections Officer Elmer Grewing gave the routine signal, "Yard out," over the loudspeaker, telling the prisoners to return to their cells. But it was also a prearranged signal to start rioting, catching reformatory guards completely by surprise. While half the inmates obediently returned to their cells, the other half began running wild inside the compound. The guards watched helplessly, but with guns at the ready to prevent an escape attempt. The rioters picked up rocks, broken bricks, baseballs, bats, and other objects and began throwing them at the guards atop the parapet and breaking windows in the buildings and guard towers.

Half of the rebels stayed outside in the compound and set fire to the carpentry shop, machine shop, brick-making plant, cannery, laundry, and the grandstand at the baseball field. They tried to destroy all the machinery in the power plant and shops by pouring sand from the brick-making plant into the mechanisms and opened all the fire hydrants, vastly reducing the water pressure needed to fight the fires. A few prisoners broke into the reformatory garage and stole a 1950 Nash sedan. They drove the car around the yard for awhile, then rammed it into the greenhouse and set it on fire.

The other half of the rioters rushed inside the cell block where they broke windows, burned mattresses and blankets, pulled plumbing from the walls, broke water pipes and flooded the floors, ripped up the barber chairs, overturned benches, demolished the reformatory kitchen and mess hall, and generally destroyed anything breakable. Startled, the unarmed corrections officers hastily retreated into the administration building and barricaded the doors.

Fighting the Firefighters

The fire departments in Monroe, Snohomish and Everett were called to the reformatory shortly after the riot began. The Monroe Volunteer Fire Department was the first to arrive with two trucks and was let into the stockade through the south gate. Unfortunately, the guards neglected to inform the firefighters there was a riot in progress. When they began deploying hoses and unloading equipment, the rioters proceeded to attack the firefighters with a shower of bricks and rocks. They covered their retreat with a powerful stream of water from a fire hose, but were forced to abandon 500 feet of line. On the parapet, guards looked on indifferently, without response, as the firefighters and trucks were chased out of the compound.

Meanwhile, reformatory officials made an emergency call to the Washington State Patrol who immediately dispatched 75 state troopers to augment the force of guards at the reformatory. Sheriff's deputies from Snohomish and King counties, as well as police officers from Everett, Snohomish and Monroe, were also sent as reinforcements. To prevent convicts from escaping, all the roads in the area were blocked and the prison was completely surrounded.

Fires raging inside the reformatory compound were visible for five miles. Huge showers of sparks and burning debris shot into the sky as portions of destroyed structures collapsed. Fortunately, there was only a slight breeze that night and the flames were contained within the stockade, sparing the administration building and the cell blocks. As a precaution, firefighters remained on duty throughout the night, outside the reformatory walls.

Entering the Fray

At about 9:00 p.m., Snohomish County Sheriff Thomas V. Warnock and Sergeant O. S. Buehler, head of Washington State Patrol's Everett Detachment, led a squad of 12 deputies and state patrolmen inside the reformatory cell blocks to quell the rioting inside. The officers, wearing riot gear and armed with tear gas and batons, were ready for action. Sheriff Warnock took a rifle inside the cell block and fired twice into the ceiling, getting the prisoner's attention. After some initial resistance, the squad quickly subdued the rebels and herded them into cells. Meantime, the rampage in the compound continued unabated.

At about 9:30 p.m., the height of the riot, a mob of prisoners gathered in front of the guard tower at the northeast corner of the yard and began a barrage of bricks and rocks, breaking every window in the tower and sending the officers ducking for cover. Anticipating a mass breakout, a guard on the wall opened fire with a sub-machine gun when the inmates advanced toward the gate. Tear-gas grenades were lobbed into the center of crowd, dispersing it immediately. After the shooting, the most rioters gravitated toward the open baseball field, leaving behind four who had been shot during the melee. Prisoners carried the wounded men to a gate on the opposite side of the compound where reformatory medical personnel could administer first-aid. Two inmates had been shot in the head and were taken to Monroe General Hospital (now Valley General Hospital) by ambulance in critical condition. The other two inmates had minor wounds and were treated at the reformatory hospital.

After the shooting incident, things began to quiet down. The insurgents generally milled about the center of the yard, shouting insults at the guards. Banks of portable floodlights and spotlights were set up on the parapet to illuminate areas where convicts would be likely to hide or attack. The large, steel gates, set in the walls, were the most critical areas. The rebels were given plenty of time to calm down before state patrolmen in riot gear, herded them away from the gates onto the baseball diamond where they could be monitored by armed guards atop the wall. Sheriff Warnock led a contingent of deputies to search for prisoners who might be hiding in the burnt-out buildings, but found none. Using tools taken from the carpentry shop, the inmates tore up the bleachers for firewood and built bonfires to keep warm. They spent the night, under close supervision, corralled on the baseball field.

The Second Day

On Friday morning, August 21, sporadic trouble broke out in the compound when a group of prisoners tried to break into the reformatory garage, but guards drove them back with tear-gas. They tried again about noon, but were chased back to the baseball field. There was no food available, since the kitchen had been destroyed, so inmates in the yard scavenged tins of fruit jam from the destroyed cannery. Eventually, the rebels, desiring food and shelter, capitulated and became compliant. However, reformatory officials still deemed the situation unsafe. The prisoners spent the remainder of the day and all night on the baseball diamond, waiting to be allowed back into their cells.

Meanwhile, Superintendent Squier ordered a complete shakedown of the two cell blocks before permitting prisoners inside from the yard. The kitchen had been ransacked during the insurrection and most of the knives had disappeared. Guards completed the search about 1:00 a.m. Saturday and reported finding over 100 handmade weapons and knives. Squier also ordered a careful inspection of the entire compound before inmates would be allowed outside again, to be certain that no knives, tools or other contraband had been hidden there.

End of the Riot

By Saturday morning, after another chilly night on the baseball field without food, the danger of another uprising seemed to have passed. About 10:00 a.m., officers began moving small groups of inmates through the gate at guard tower six where they were searched for weapons and contraband, and then escorted to cells. By early afternoon, all the rebels had been cleared from the compound and locked up. A subsequent headcount confirmed that all the reformatory inmates were accounted for. Superintendent Squier suspended visitations and other privileges until further notice. Arrangements were made for hot meals to be brought to the reformatory, but prisoners had to eat inside their cells to prevent any new outbreaks of violence.

In Olympia, Lieutenant Governor Emmett T. Anderson, acting for Governor Arthur B. Langlie, immediately demanded a full-scale investigation and ordered Attorney General Donald Eastvold to launch an inquest. He sent assistant Attorney General Frank Hayes to Monroe to meet with Snohomish County Prosecutor Philip G. Sheridan and reformatory officials to determine whether criminal prosecution of the ringleaders, should they be identified, was feasible. Those responsible for the melee could be charged with assault, destruction of state property, arson, and inciting to riot. However, the likelihood of obtaining corroborating testimony from other inmates, needed for convictions, was remote.

Investigation

The investigation into the cause of the riot started on Saturday afternoon, August 22, 1953.

Among complaints of intolerable conditions, inmates told the investigating committee the direct cause of the riot was the unnecessary brutality used to discipline Ernest Jack Taylor, a black male, age 18, serving 15 years for grand larceny. They claimed he had been brutally beaten with chains in retaliation for disobeying instructions.

Guards claimed the problem was their inability to maintain discipline because they had no backing from the administration. The inmates knew that nothing would happen if they were reported for infractions, even serious ones like carrying concealed weapons, assaulting a guard, or attempting escape.

The investigation revealed that Taylor, a janitor in the cannery, refused to follow an assignment that he claimed was unnecessary. On Wednesday morning, August 19, his insubordination was reported to the reformatory's "adjustment committee" (disciplinary board) to decide on what disciplinary action to take. After a hearing on Thursday morning, the three-member committee decided to place Taylor in "deadlock" (solitary confinement) for an indefinite period. Taylor refused to comply with the sentence and had to be forced into the deadlock cell. He had been slightly injured on the way to deadlock when he allegedly attacked the escorting officers. Supervisor Squier told the investigating committee that Taylor had been examined by the reformatory's doctor after the incident and, except for a few bruises, was basically uninjured.

Aftermath

On Sunday, August 23, reformatory officials and engineers from the state Department of Public Institutions began an intensive survey of the riot damage and formulated plans for putting vital facilities back into operation. On Monday, Harold D. Van Eaton, state Supervisor of Public Institutions, announced that only two of the reformatory buildings had been damaged beyond repair: the laundry and the cannery. The other buildings, constructed primarily of brick, could be renovated and he estimated the damage would not exceed $800.000.

On Tuesday afternoon, September 1, 1953, members of the Legislative Committee on State Institutions convened in the reformatory auditorium to determine the underlying causes of the riot and to ascertain if outbreaks of violence could be avoided by legislative action. The committee consisted of three State Senators: Neil J. Hoff. Tacoma, committee chairman; Howard S. Bargreen, Everett; and Albert D. Rosellini (1910-2011), Seattle; and three State Representatives: Dewey C. Donohue, Asotin County; Harry A. Siler, Lewis County; and Robert D. Timm, Adams County. Assistant Attorney General Frank Hayes, representing the governor's office, also attended the session.

What Went Wrong

Witnesses included Superintendent Squier; two former reformatory superintendents, Ray Ryan and Earl Lee; reformatory administrative officers and staff; law enforcement personnel, who had been present during the riot; and a number of inmates, who were screened from the assembly and testified anonymously. The hearings were broadcast live by radio station KRKO and KING, as well as KING-TV.

The topics covered a wide range of subjects including morale, mismanagement, dissension among the employees, favoritism, prison security, smuggling of contraband into the institution, gambling, alcohol abuse, drug trafficking, violence and brutality inside the reformatory walls, and the shooting incident that left one inmate dead.

Some of the most surprising revelations came from reformatory staff. Benjamin Wright, Supervisor of Classification and Parole, testified that the state Department of Corrections considered the reformatory a second-rate prison, and forced it to house hardened criminals who should be incarcerated at the Washington State Penitentiary. He said the reformatory even housed eight psychopaths due to lack of space at the state mental institutions to which they had been committed.

Dr. C. Arthur Elden, the reformatory physician, testified that after an afternoon visit to a cell block on the day of the riot, he felt tension among the inmates and that trouble was coming. A group of inmates had congregated around Ernest Taylor's cell, discussing a beating he had allegedly received after objecting to being placed in solitary confinement. Dr. Eldon met with assistant Superintendent John L. "Cap" Brady and warned him: "For God's sake, don't have yard-out tonight." Brady said if the inmate's routine is changed, "they'll think we're cowards" (The Everett Daily Herald).

Superintendent Squier testified about his attempts to remove Assistant Superintendent Brady, who had been at the institution for more than 30 years. Squier said he could not carry out his program of reform as long as Brady remained on staff, undermining his authority. He told the committee that Brady frequently countermanded his orders, upsetting morale and causing considerable confusion. Other staff members substantiated Squier's position, testifying they sometimes didn't know who was in charge.

Former reformatory Superintendent Ray Ryan had Brady replaced during his administration (1945-1949). He told the committee: "This institution will never be run well with Mr. Brady there" (The Everett Daily Herald). Ryan said the dire situation at the reformatory would continue unless and until there was a high level shakeup and went on to name names.

The committee concluded the hearings late Thursday afternoon, September 3, concluding the riot was the climax to years of corruption, scandal, and unrest at the institution. The problem was amplified by the state's propensity to use the reformatory as a dumping ground for prisoners who should clearly be housed elsewhere.

Cleaning House

On Friday, September 4, Director of State Institutions Harold D. Van Eaton telegraphed Superintendent Squier: "This wire confirms authorization for you to make personnel changes immediately to assure proper administration and security at the state reformatory. I request you utilize all means available to this end and report to the department any special assistance you may require" (The Everett Daily Herald). Squier immediately dismissed assistant Superintendent Brady and told the news media other changes would follow. As expected, Brady charged that Squire was using him as a "fall guy" for the riot and refused to resign. Squier pointed out that Brady wasn't expected to resign; he had been fired.

On September 19, Superintendent Squier announced the dismissal of seven more reformatory staff members. The explanation for their dismissals was their uncooperative attitude.

Assistant Superintendent Brady was replaced by Lawrence Delmore, age 50, retiring assistant warden of Alcatraz Island Federal Penitentiary. Delmore was considered one of the nations top experts in penal affairs. Paul Squier continued as Superintendent of the Washington State Reformatory until his retirement in 1956. He was succeeded by Roy Belnap.

Testimony during the three-day hearing failed to determine who had fired shots at the rioting inmates. According to the Snohomish County Prosecutor's Office, the investigation was still in process. But, as far as the guards were concerned, it was better left unsaid. Lyshall's fatal wound was ruled a death by misadventure while participating in unlawful acts.

Wounded inmates:

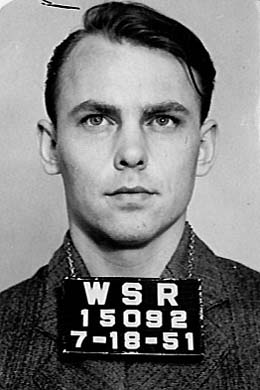

- Walter Thomas Lyshall, age 21, serving 10 years for auto theft, was taken to Monroe General Hospital where he died from a head wound.

- Glen M. Anderson, age 25, serving 15 years for grand larceny, was shot in the head and blinded. He was taken by ambulance to Monroe General Hospital in critical condition. Anderson, incapacitated, was granted a 90-day leave of absence on October 21, 1953, and subsequently pardoned on February 25, 1954.

- Richard Phillip Brattain, age 22, serving 10 years for burglary, was treated for a scalp wound at the reformatory hospital.

- Douglas Farris, age 20, serving 10 years for auto theft, was shot in the ankle and hospitalized at the reformatory.

Injured Officers:

- Chief Criminal Deputy Edwin O. Walker, Snohomish County Sheriff’s Department, fractured ribs in a traffic accident while responding to the riot at the Washington State Reformatory.

- Sergeant Marvin Paulson, Washington State Patrol, Lewis County Detachment, suffered facial injuries when his tear-gas gun backfired.