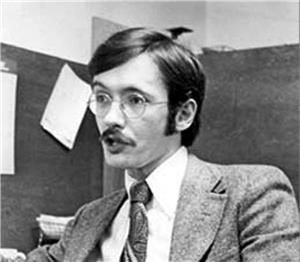

This is a talk on the Vietnam War presented by Walt Crowley (1947-2007) in September 1984 at the Seattle Center. Walt was invited to speak as a writer for the "anti-war tabloid," Helix, to a gathering consisting almost exclusively of Vietnam veterans and their families. The Vietnam Veterans Leadership Program sponsored the occasion. Walt presented his talk before a photo-mural of Maya Lin's Vietnam War Memorial, the original of which is carved in black marble and is located on the mall in Washington D.C. The talk reprinted here appeared in the Seattle Weekly and follows the Weekly's introduction to it.

Introduction by the Seattle Weekly

Last week [September 1984] a half-scale photo mural of the Vietnam War Memorial was displayed in Seattle. The actual memorial, of course, is located in Washington DC. It is a black marble salient cut into a grassy sward near the Lincoln Memorial, bearing the names of the 57,692 American men and women who fell in Vietnam between July 1959 and May 1975 in the order of their deaths.

Although initially controversial, the memorial has come to be accepted by Vietnam veterans and the public as one of the most moving public monuments ever constructed. The effect of the photographic reproduction displayed at Seattle Center was no less powerful.

The display of the mural and companion artwork by veterans was organized by the Vietnam Veterans Leadership Program as part of its “Coming Together Again” campaign to help veterans reassimilate into society. The VVLP held an official ceremony on the evening of September 19 to open the exhibit, and veterans and relatives of dead or missing Americans spoke briefly of their feelings. The project’s chairman Lee Raaen and ceremony organizer Gale Ensign also invited Richard Posner, a conscientious objector during the war, and Walt Crowley, then a writer with the anti-war tabloid Helix, to offer their perspectives.

The crowd, consisting almost exclusively of veterans and their families, accepted these two ”outsiders” graciously. And when the ceremony concluded with a moment of absolute silence and then the playing of “Amazing Grace” on a lone bagpipe, all who attended were truly united emotionally. It was an extraordinary experience.

Here is Crowley's talk.

The War We Won by Walt Crowley

I am very honored to have been invited to share with you what must be a very important, private, and for some, a painful experience.

I am also humbled to be in the presence of this memorial to the scores of thousands of men and women who lost their lives during the Vietnam War.

The Leadership Program asked me to speak to you today as a representative of the “anti-war movement.” I cannot do that for two reasons.

First, it implies that one person could speak for all of the millions of people who ultimately came to criticize or oppose military and political intervention in Vietnam. The spectrum of views and the range of feelings reflected and expressed during the national debate over Vietnam are simply too great for a single person to embrace or articulate.

It would be equally false to suggest that one person could speak for all of you here, or for all of the veterans of the Vietnam War, or for all of the 58,000 people named behind me. They and you do not speak with a single voice.

Secondly, for me to attempt to speak for a movement that unraveled and dissolved with the war it opposed a decade ago would perpetuate a false and dangerous polarity in our society. It would endorse the myth that the debate over Vietnam has—and continues to have—only two sides: an anti-war side and a pro-war side; a right side and a wrong side; a good side and a bad side.

Such a construction is not only not true: it is destructive. It smothers debate and reasoning. It preserves the isolation of the Vietnam veteran from his and her community. It represses our ability to share your horror and honor your heroism. It preserves and reinforces the barriers between Americans that prevent us from coming to understand and then move beyond our national experience in Vietnam.

Foremost, it poisons the root of reconciliation which we have all come here, in the shadow of this monument, to nurture.

So let us instead begin with some basic truths:

First, let no one ever tell you that the Vietnam veteran failed America. It is you who have been failed by this nation’s political and military leadership.

Secondly, let no one ever tell you that the decision to obey is any easier than the decision to object. To serve is no less an act of conscience than to dissent, and for thousands, the price of service was the highest a human being can pay.

Third, let no one tell you that the Vietnam veteran must bear responsibility for the events of the Vietnam War, the you are at fault and the guilt for policy or error is yours.

I say that there is no shame where there is no blame.

And finally, let no one tell you that the American soldier or the American people lost the Vietnam War. You did not lose this war; America did not lose this war.

In a fundamental way, America won the Vietnam War. That is the truth some would try to hide by burying the veteran with the dead. But they cannot succeed because you are the living witnesses of that victory of human spirit which is expressed in a simple but binding pledge, a pledge that all of us must make to those named here:

The pledge that no single American shall ever again be sent to die alone in a war that all Americans are unwilling to fight or unprepared to win.

If we keep faith with this pledge, then your service and their sacrifice shall have secured the greatest victory in our history.

September 1984 – Seattle Weekly