Hillyard, known today as a neighborhood in Spokane's northeast quadrant, began as a separate town in 1892. It was built around the Great Northern Railroad's rail yards and named after Great Northern magnate James J. Hill (1838-1916): literally, Hill's Yard. Before that, Hudson's Bay fur traders referred to Hillyard and the surrounding areas as Horse Plains or Wild Horse Prairie. Hillyard was first platted as a townsite in 1892 when the Great Northern Railroad arrived and chose this flat ground as the site for its rail yards, machine shops, and roundhouse. By 1895 it had 486 residents, but as the rail yards expanded over the next two decades it experienced a boom in population to about 4,000 by 1916. Many of these new residents were immigrant laborers, and Hillyard came to be known for its Italian and Japanese neighborhoods. In 1924, Spokane annexed Hillyard and it has been part of the city ever since, retaining its own industrial, blue-collar character. Hillyard has long been known as an economically depressed part of Spokane, a problem exacerbated by the closing of the last remnants of the rail yards in 1982. Hillyard continues to have one of the lowest per capita income levels in Spokane and in the state. Yet it also has well-groomed neighborhoods, a golf course, and a thriving antiques district. New residents from Russia and Southeast Asia have recently arrived, continuing Hillyard’s legacy as a haven for immigrants. The neighborhood's historic business district is on both the Spokane Register of Historic Districts and the National Register of Historic Places.

A Prosperous Suburb

Despite Hillyard's later reputation, the village began as what the Spokane Spokesman-Review called a "prosperous suburb." Three years after the plat was filed in 1892, Hillyard already had 486 people, a hotel, three churches, and six saloons. By 1895, the Great Northern's yards included a 20-stall engine house, a paint shop, a car shop, a blacksmith shop, a boiler shop, a machine shop, a storehouse, and offices.

"Here anything in the car or locomotive line can be made or repaired," wrote the Spokesman-Review. The paper reported that only 40 men were employed in 1895, but predicted, correctly, that the number was soon to leap.

There was continual talk of incorporating the town in those early years, and in 1895 an incorporation measure was passed by the narrowest of margins: 45 in favor and 44 against. However, incorporation did not last long. Less than a year later, another voice was heard from -- a voice the town could not ignore.

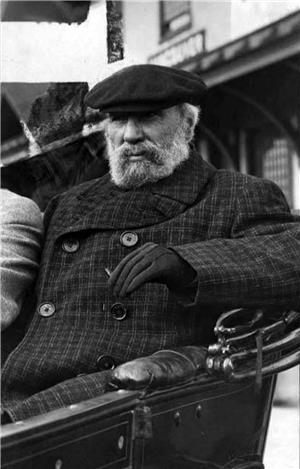

Hill Stirs Up the Town

"Jim (James J.) Hill was in Hillyard just an hour and a quarter yesterday, but in that time he stirred up that brisk suburban town as it had never been stirred up before," said the Spokesman-Review in 1896. "In plain terms, he said that incorporation must be vacated or he would move the shops; that there must be no delay about it, or the 1st of April would see only the shells of the buildings left." (S-R, "Stir at Hillyard)

Hill had purposely built the yards outside city limits to avoid what he called “burdensome taxes” and he had no intention of allowing that situation to change. The alarmed citizens were convinced that Hill meant business, so they convened a meeting that night and dissolved the incorporation.

"Now peace reigns once more," sardonically noted the Spokesman-Review in 1897. "All this was given wide publication through the newspapers, but the advertising was not of the kind to help the town much" ("Bright Future for Hillyard").

A Railroad Town

In 1897 the town was already facing some of the social and economic issues that would later define its character. Although Hillyard was noted for its "neat, homelike residences," it was also known for its many tenements, because "there are so many railroad people who are of such a migrating class that they seldom own their own homes," said the Spokesman-Review ("Bright Future for Hillyard").

By 1899, the paper reported that Hillyard had the most extensive rail shops of any place west of St. Paul and was also the headquarters of 14 or 15 regular train crews, of five men each. By 1900, the Great Northern employed 350 people.

With all of those railroad workers came the usual auxiliaries. After Spokane cracked down on "fallen women" in 1904, up to 40 "of the class who ply their vocation" had moved into Hillyard.

"They have shoved us out of Spokane and we must live somehow," one of the women was reported as saying ("Fallen Women at Hillyard").

In 1904, the citizens hit on a clever compromise to the incorporation issue. They incorporated the town of Hillyard -- but left the massive rail yards and shops outside of the incorporation.

Labor and Labor Tactics

With so much blue-collar labor, union unrest and strikes were frequent. Some of these strikes shed light on the social divisions that were agitating the country during this time of mass immigration. During a Hillyard machinist-helpers' strike in 1911, the company brought in what the Spokesman-Review called a "band of Italians" to break the strike.

"Last night the machinists' union called a special meeting and decided not to work with the foreigners," said the Spokesman-Review. "They demand white assistants and will walk out sooner than work with men who cannot speak or understand the English language" ("GN Strike Far From Settlement").

Over the years, the company succeeded in bringing in immigrant laborers, especially Italian and Japanese. When Japanese workers came in to break a strike in 1904, they were housed in converted boxcars. Soon the Italians and Japanese had established their own neighborhoods within Hillyard. For many decades, some Hillyard blocks were considered Spokane's Little Italy, with Italian produce stands and restaurants. Meanwhile, some Japanese families went on to open thriving businesses, such as the Hillyard Laundry.

Mayor Goes Plumb Bugs

With all of that union labor, Hillyard had developed a socialist political bent around 1910. In 1913, socialist Jared Herdlick was Hillyard's mayor -- but not for long. In June of that year, Herdlick stopped showing up in his office or at city council meetings. Even his wife didn't know where he was. He just plain disappeared.

And then, three months later, came the starting news: He had surfaced in the hills around Portland, claiming amnesia. He wrote a letter to his wife claiming that he had suffered a memory lapse, "obliterating for three months all cognizance of his personality, relatives and social and political interests." He had even forgotten he was mayor of Hillyard.

Then, three months later, he showed up and demanded his job back. He declared that he didn't know what had happened to him, except to say that "the horrible gray wolf called capitalism drove me plumb bugs"("Herdlick Wants His Mayor Job").

When it was clear that he would not be welcomed back with open arms, he withdrew his demand, apologized for causing any trouble, and quietly withdrew from the public scene.

Annexation

By 1924, Spokane had grown to the point where it was lapping up against Hillyard's borders. Spokane had long been interested in annexation, but Hillyard residents were deeply split. Hillyard voters defeated a March 1924 annexation referendum, 600 to 595. Another election was immediately called. In September 1924, Hillyard residents voted 808 to 681 to become part of Spokane. Jim Hill was no longer around to protest -- he had died in 1916 -- but he didn't need to. The Great Northern shops remained outside of city limits.

Some Hillyard residents weren't wild about the change however. Among other things, it meant that all of Hillyard's street names -- except the main streets of Market and Diamond -- were changed to conform to Spokane's street names. Some of the old street names can still be seen, stamped in the concrete on sidewalk corners. Hillyard City Hall became a fire station.

The center of community life continued to be Hillyard High School. One longtime teacher recalled: "It was Prohibition days then and Hillyard was a tough town. I had the son of the principal bootlegger in one of my classes" (Barnes).

A new high school for the area, John Rogers High School, was built in 1932 and continues to be an important Hillyard community center.

Behemoth Locomotives, Hillyard-Made

The rail yards, still thriving, took on an even more important role in 1927 when the Great Northern decided it needed a fleet of freight locomotives bigger than any yet built, powerful enough to haul 5,000 tons over the Rocky Mountain passes. The company intended to order the locomotives from one of the big Eastern factories, but the Hillyard shop men talked executives into letting them build the fleet right there in Hillyard.

"At the time, no locomotive had ever been built west of the Mississippi," said the Hillyard foreman years later. "As a matter of fact, no engine had yet been built completely new in any American railroad shop. And to tell the truth, none of us at Hillyard had even been inside a locomotive works" (Perrin).

The first behemoth, called a class R-1 Mallet, steamed out of the Hillyard shops in November 1927. In 1928, the shops were churning out one a month, and over the next few years built at least 26.

Sober Agnes Kehoe

Hillyard has a long history of producing colorful politicians, as well.. The best known throughout the state was Agnes Kehoe (1874-1959), who served four terms in the Washington State Legislature beginning in 1938. She never actively campaigned, but had no trouble getting re-elected on the basis of this simple platform: She promised never to get drunk and never to sell her vote.

Kehoe’s contributions far exceeded those modest goals. She first came to Hillyard in 1903 with her husband, who had landed a job in the rail yards. She soon became a prime mover in the Hillyard branch of the Social Service Bureau, the era’s main provider of charity and welfare services, as well as the Community Chest and Spokane Women's Club. She founded the Visiting Nurses Association and for decades was instrumental in almost every community initiative.

When the Great Depression hit, a group of Democrats and Republicans urged Kehoe to run for the legislature, on the grounds that “responsible citizens” were more necessary than ever in the legislature. She resisted for several years, largely because her husband, who then ran the Kehoe Hardware Market, felt that "a woman’s place was in the home."

"Finally, I guess they wore down his resistance," she said in a later interview. "He said, 'Well, she can file if she wants, but I won't vote for her.' Nevertheless, I think he voted for me" (Prager). At the time she was one of only eight women in the 145-member legislature.

From Steam to Diesel to Tourism

The rail yards continued to be Hillyard's economic heart through the war years, but when diesel power began to replace steam power in the 1940s and 1950s, it appeared that the Hillyard shops would go into decline. A reprieve came in 1954, when the Great Northern turned Hillyard into its major Western diesel locomotive repair and overhaul facilities.

The reprieve was short-lived. Railroads throughout the United States were hurt by competition from semi-trucks and airplanes. In 1968, the Great Northern merged with the Northern Pacific to become Burlington Northern, and the shops at Hillyard were cut back to "local service." The work force was slashed as workers were transferred to Montana and to other freight yards.

Hillyard never fully recovered from this blow, although the community struggled to find a new economic base. A community group calling itself the Hillyard Development Corp. came up with a plan to convert Hillyard's rail yards into a tourist attraction, what they called the "Disneyland of Spokane." The group planned to convert the central core of Hillyard into a turn-of-the-century village with a railroading motif. They organized the Hillyard Tours, in which passengers boarded special trains in Hillyard and went on scenic trips to Newport, Republic, Colville, Chewelah, and Kettle Falls. The first trip in 1968 attracted 260 passengers and was deemed a smashing success.

But the dream quickly faded. By 1969, ridership had dropped and trips were cancelled. The railroading "village" never materialized. In 1970, boosters were blaming Burlington Northern for not helping out enough. They said that the railroad had jacked up the prices of train rental and refused to let a refurbished steam locomotive run on its tracks.

"To let Hillyard, the center of early-day railroading here ... simply die an economic death while the weeds and debris take over the yards and the old roundhouses -- scene of all the early bustle -- would be sad and wasteful neglect," the boosters said in a letter to the Burlington Northern president (Cross).

The excursions soon ceased. The weeds and debris continued to proliferate in the old yards throughout the 1970s until the final remnants of the yard closed in 1982.

"I'm Frum Hillyurd ..."

Hillyard became stereotyped, often unfairly, as Spokane's neighborhood for the undereducated and underemployed. In 1975, Superior Court Judge George T. Shields caused a Hillyard uproar because of comments he made in sentencing a man for a Hillyard shooting incident.

"There are only three things that come through about Hillyard," said Shields. "One is everybody drinks or is drunk. Everybody fights or is about to … and the third thing is that everybody is armed" ("Judge Comments During Sentencing).

Hundreds of Hillyard residents signed a petition demanding that Shields "rescind" those remarks. Shields later tried to "clarify" his feelings about Hillyard by saying that he was referring only to a specific Hillyard tavern, which had been the scene of two recent shootings.

The judge was guilty of, at the very least, making gross generalizations, but he was only expressing what much of greater Spokane was already thinking. Hillyard had become synonymous in Spokane with "rough" and "lower class," even though many of its residents and neighborhoods defied that stereotype. Eventually, Hillyard residents found a way to poke fun at the stereotype. During one city election, bumper stickers appeared in Hillyard reading, "I'm Frum Hillyurd and I Voat."

While Hillyard continues to struggle with economic problems, it has many energetic civic associations, including the Greater Hillyard Business Alliance, the Hillyard Council, and the Hillyard Festival Association, which sponsors several yearly community festivals.

Hillyard Today

As of 2007, Hillyard remains one of the poorest areas of the city. The average house price is about half of the Spokane average. For this reason, Hillyard continues to be attractive, as it was in the 1910s, to first-generation immigrant families. The immigrants today are often Russian and Southeast Asian.

Hillyard has also been active in preserving its historic heritage. Over 85 percent of central Hillyard's historic buildings are still intact, many built before 1910. In 2002, the Hillyard Market Street District became the first Spokane neighborhood to be accepted onto the National Register of Historic Places. The Hillyard Historic Business District was placed on the Spokane Register of Historic Districts in 2004.

A drive has also begun to build a Hillyard Heritage Museum. A proposed visitor's center still awaits funding, yet the museum already has a few outdoor displays that perfectly symbolize the history of Hillyard: Several historic rail cars, open to the public upon request.