This People's History consists of excerpts of interviews recorded in 1984 about childhood experiences of Seattle-area winter holidays in the 1920s. They are taken from oral histories in the collection of Seattle's Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI). The museum's Sophie Frye Bass Library has archived more than 300 oral history interviews, recorded since the 1960s with a wide variety of narrators, over a broad range of topics. The conversations exerpted here were recorded when most of the narrators were octogenarians recalling a decade when they were children. They were edited by MOHAI historian, Lorraine McConaghy, Ph.D.

Their memories open metropolitan Seattle to us during the “roaring twenties,” though the 1920s didn’t roar much in western Washington. The recession that followed on the heels of World War I cut prices on the very items that Washington produced in abundance: coal, salmon, and lumber. Jobs were hard to find and times were tough, and these narrators remembered a simple holiday time, when people made a little go a long way. The first things to be forgotten in history are the everyday moments that seem inconsequential. It is easy to learn how many people were counted in Seattle in the 1920 census or who was elected president in 1924. It is far more difficult to learn how people actually lived in 1920 -- what mattered to them, how they cooked and dressed, and, yes, how they spent their holidays. Here are some memories of that time and place. The narrators include Lily May Anderson, Bibiana Castillano, Priscilla Kirk, John Kusakabe, Lucile McDonald, Lydia Offman, Greta Petersen, Jean Sprague,

Amelia Telban, Ethel Telban, and Louise Yook.

Holiday Memories

In the 1920s, we made gifts for our parents at school. I remember in first grade we made a little calendar. It was just a piece of red paper -- at the top we pasted a Christmas picture cut from an old holiday card and the teacher gave a tiny little calendar to each of us, and we pasted that on. And later on, I think about the 5th or 6th grade, we girls made handkerchiefs for our mothers. They were made of peach-colored cotton -- I remember our teacher, Miss Gill, taught us how to embroider. It was very simple, we only did a few stitches at each corner, but I remember how thrilled I was to learn how to do that. Then another year, I remember, the boys made door stops. The school principal went over to the Denny-Renton brick yard and got a pile of bricks and the boys painted them red or green, and then painted a design on them. Another time, we made an apron for our mothers as a Christmas gift, and it was quite an ambitious project. We had an awful struggle because we had to appliqué a design onto it. And another gift I remember making was a hot pad. And that was made with a piece of cardboard for a base, woven around with white and red raffia. That turned out okay, and it was a practical gift, too. We made gifts for our parents at school, for all my growing up time.

I was a little girl then, and we had a big two-story house in Kirkland, with a full basement and an attic besides, and it had two bedrooms and one bathroom. At Christmas time, the tree was always in the room we called the parlor, and it practically filled that tiny room. I don't suppose the room was more than eight feet square, and the tree went clear to the ceiling. My parents trimmed the tree, and it was lit with candles because nobody had electric tree lights in those days. When we were really little, I was a great one for dolls. I had a baby doll, and he was about 10 inches long and he had a bald head, like babies do. He was sort of like a real baby, and I wanted a baby bed for him. And I remember peeking through the keyhole and seeing this bed under the Christmas tree, and, oh, I was so delighted, I could hardly wait to get it! My father had made the bed but my mother made sheets and a nice blanket and a pretty bedspread and a little pillow. And, of course, the doll baby was in the bed and, oh my goodness, I was so delighted! My brother wanted a sled, and he got that for Christmas -- I thought it was a very dull gift, until the snow fell!

Well, when I was young, we lived on 19th and Cherry, in Seattle, and it was a very international neighborhood. I just loved living there because we had all kinds of people -- we had white families, and two or three black families; we had Japanese and Chinese and Jews. I’m always thankful that I grew up in a neighborhood like that. My Dad was a watchmaker, and he had a store on First Avenue in Pioneer Square. I think he was pretty prosperous because we had a car before a lot of other people did. And we owned our home, too, and didn’t rent. We attended the Bikur Cholim Synagogue, at 17th and Yesler. That’s the orthodox synagogue. But my mother sent me to Temple de Hirsch because they had a very good Sunday school. When we were little kids, my folks used to put out presents for us on Christmas Day so we would have them, too, like our Christian neighbors. In fact, we would hang our stockings, and they’d be filled with Japanese oranges and candies. But as we got older, that stopped. I mean, Hanukkah isn’t Christmas. It’s a very different story. It just happens to come at the same time. In school -- at Minor and Garfield -- my folks let me be in on the Christmas programs because I liked music so much. I would sing in the programs because I could carry a tune, and when it came to Christian words, the teachers would say, “You can hum.” So I just hummed.

When I was a girl, we lived out at Green Lake, and our home was small but comfortable -- we were the only Black family out there -- we were called “Negroes” then. At Christmas, we always had a tree -- you could buy one at the Pike Place Market for a quarter. I recall my father going to the Market to bring back a sack of candy for us. In those years, the candy was in forms of little fish or little animals. Our Christmas trees were very small, and we always had lighted candles and we were always warned to be very careful with the candles. The decorations were mostly made of paper or popcorn -- we would pop the corn and string it. Sometimes it was colored, but usually just the white popcorn. We had long, silver tinsels that we draped around the tree. And since we didn't have a fireplace, our little stockings were pinned up on the wall. And how we looked forward to Christmas morning! I really believed in Santa Claus. We had a coal-burning stove, and I always worried about him coming down the chimney. And we would always gather around the tree to open our packages. Our Christmas presents mostly were homemade, but we always had plenty of goodies, special things that my mother baked.

In December there is a period known to Japanese as Oseibo -- “end of the year.” Oseibo is a custom that I don't believe is religiously motivated, but families would give gifts of appreciation and good will to other families. By chance, Oseibo hit just around Christmas time, and therefore they went more or less together. But the commercialized Christmas doesn't enter into Oseibo -- you would give, for instance, a sack of rice to a family. Something practical in appreciation for their support and friendship. The children would receive packets of candy, or a little envelope with a couple of pennies. I asked my parents why we as Buddhists were observing this gift-giving thing with such gusto, passing cards and so forth and so on, like the Christians were doing. And their answer to me was that Oseibo is a longstanding Japanese custom and, also, that there is nothing wrong in following the customs of your new neighbors. As a family, we just observed the gaiety of the period. You couldn't help but get caught up in it. But we never did use the term “Merry Christmas” on our greeting cards. It was always "Season's Greetings,” or "Oseibo."

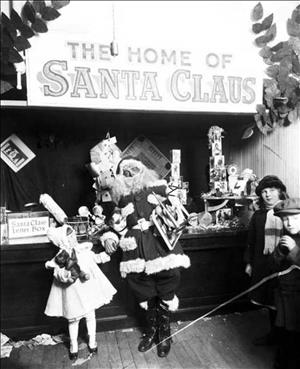

Our parents were both born in Slovenia. They learned German in school, and they each spoke their own village dialect. But both of them spoke English here, and they were very anxious to be Americanized, and for us to be Americanized, too. I remember Mother talking about always on Christmas Eve in Austria, they would shampoo their hair with special scented water made with flower petals saved from the summer before. And she told us about going to midnight mass in the old country, too. It really must have been beautiful when they came down out of the snowy hills in a sleigh, down into town and through the doors of the church, filled with lighted candles. One Christmas tradition that we continued in America was that our mother made a special walnut bread -- just that one time a year. It was a sweet dough that you rolled out, spread your filling of walnuts and honey, and then rolled it up to rise and bake. It's really good. Mother would tell us about how as a child, she expected Santa Claus to visit. And I believed in him wholeheartedly, too. I remember going into the Bon Marché in downtown Seattle once with Papa on the streetcar and seeing Santa. And the Bon had a special Christmas display for children -- it was a wonderland. I remember walking through it and being thrilled to pieces.

We came from Denmark to Seattle. Back home, we celebrated on Christmas Eve. That's when we had all our gifts and things, and we danced around the tree, singing the Christmas hymns. And we didn't have Santa Claus, like you do here for Christmas. But we have what we call the Julenisse and he was a sort of troll. And the kids were supposed to put porridge out for him -- if you put porridge out for the julenisse that's good luck. But there's not just one of them, there's many. In Danish Christmas scenes, you'll see a little julenisse instead of Santa Claus. But here in America, we kept a Danish tradition on Christmas Eve -- we made a rice pudding, a porridge. And there was one almond hidden in the pudding. Whoever happened to get the almond, there was a present standing on the table that went to that lucky person. I can remember us all -- maybe 12, 15 people -- all seated around the table, eating that delicious pudding, and watching each other -- who would find the almond?

Our family came to Seattle from Suwatao, in China, not too far from Hong Kong, between Hong Kong and Canton. My father came here to become the minister of the Chinese Baptist Church in Seattle. We did have a Christmas tree, and my older sisters say they remember decorating the tree. We stayed up almost all night on Christmas eve, decorating the tree. It always was a big tree. They'd string popcorn and cranberries, and we made double-happiness signs, you know, the Chinese word "double happiness"? We cut them out of red or silver foil, and they were so pretty to hang up and use on the tree. We kept them for New Year's decorations, too, those happiness signs. For Christmas gifts, each of us kids got a $2.50 gold piece on Christmas. They were tiny -- about the size of a dime, I think. We always cherished them for as long as we could stand it, admiring them, and then finally, we’d spend our present to buy something wonderful.

My parents had only been in the United States for a few years, but they wanted to do things the way the Americans did and so we had a Christmas tree with really pretty ornaments. Down here in Renton, the woods were still close by. So we'd go up there where it was logged over and all the first growth was gone but there were lots of second growth trees, and we had a big choice of Christmas trees. We would all walk around and pick out our tree, and our father would cut it down. He made his own stand for the tree because we bought nothing in those days that we couldn't make for ourselves. I remember we hung little illustrated cards on the tree, small ones trimmed with gold tinsel all around. And there were a couple fancy ornaments, too -- the one I liked the best was a brightly painted glass bird with a shiny tail that clipped on the branch. Everything was so special because we only saw these pretty things once a year. They were stored away in the attic and there was a special box to keep the ornaments in. It was a huge chocolate candy box with chrysanthemums painted on top in a raised design -- it was the most beautiful box I had ever seen.

In the Philippines, Christmas was a very religious holiday when I was a girl. For nine days, every day the church was full. No matter how far away you lived -- even way far out in the country -- you had go to town to attend the mass. It was an obligation. But when we came to Seattle, Christmas was very different. We only went to mass on Christmas eve. I bought a nativity scene, here in America, to decorate. We lived in a boarding house -- my father and mother were the managers -- and we bought one tree -- a very big tree -- and decorated it from top to bottom. Everyone enjoyed it so much. All the people in the boarding house gave presents to us and we gave presents to them, too. Whatever you could afford or whatever you like. Not especially special -- just a little something, something to remember people by. A pair of socks or mittens, some candy or some nuts and raisins. And we always had a big dinner on Christmas Day. We served Philippines food like adobo, pansit, and dinardaran -- and turkey, too, for Thanksgiving and Christmas. So a little bit of the Philippines, and a little bit new, too.

All through the years, we'd sing Christmas carols as a family. It's the joyous part of the season. And it's a time to be thankful for your blessings. Back then, we sure didn’t have much but we always shared with others who were less fortunate than we were. Back then, salaries were so small. And it was hard, too, for some people just to get around -- nobody had an automobile, and we all got around on the streetcars or else we walked. So neighbors took care of neighbors, especially older folks. The neighborhoods were closer-knit than they are now, and more family-oriented. You knew all your neighbors, and you shared. That was one thing that was really always nice. Wherever we lived, we always had lovely neighbors and we would be congenial, thinking about each other, and especially at Christmastime. We'd go from house to house, and sing our carols, and spread our Christmas joy and take our little gifts to them -- a plate of cookies, or some fruit and nuts. They might not be much, but we shared what we had.

These excerpts are edited from interviews that can be found in their entirety at Seattle’s Museum of History & Industry.