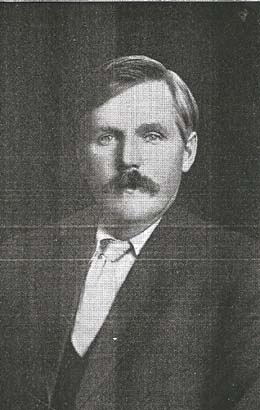

Lee Monohon was one of the original 14 charter members of the Washington State Good Roads Association, and was its last surviving charter member. Born in Oregon, he arrived in Seattle in 1871 at the age of 13. As a young man he became interested in civil engineering, and helped survey the Northern Pacific railroad track across the Northwest before settling on May Creek (today [2007] in the northern part of the city of Renton) in 1884. He mined and worked in Canada's Yukon Territory and in Alaska for a dozen years during the 1890s and 1900s. But he is particularly remembered as a major player in the Good Roads Association during the early decades of the twentieth century, while at the same time continuing his career as an engineer and taking an active role in Renton's civic affairs. Blessed with good health, Monohon lived well into his 90s. He died in July 1951, three months after his 93rd birthday.

Early Years

Lee Monohon was born on April 25, 1858, near Roseburg, Oregon. He was the son of Martin Monohon (1820-1914) and Isabelle Monohon (1824-1912). (Martin Monohon would later become known as one of the first white settlers on the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish.) He lived in Oregon and Idaho as a young boy, and moved to Seattle with his family in 1871.

Young Monohon completed his schooling in Seattle. The family remained in Seattle until 1877, at which time Martin moved to the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish in what is today the southern part of the city of Sammamish. Lee is reported to have helped his father “clear and develop the homestead” (Bagley, p.870), but whether this was on their Seattle property or the property east of Lake Sammamish is not recorded (perhaps both).

Mining and Engineering

During the early 1880s Monohon worked as miner in Skagit County. He then worked in the engineering corps of the Northern Pacific Railroad for several years, and assisted in surveying the track that was under construction between Bozeman, Montana, and Wallula (Walla Walla County), Washington. In 1884 he returned to King County and purchased a 320-acre ranch on May Creek, in what would later become the northern part of Renton. He cleared his land, cultivated 200 acres, raised crops, and operated a large dairy. But he was restless, and when the Klondike Gold Rush kicked off in 1897, he seized the opportunity and went north. He spent 12 years in the Yukon and in Alaska. He mined for a few years and “was fairly successful in his search for fortune” (Bagley, p.870), but he also built roads there, and as a result became fairly well known in the Yukon, particularly in the town of Dawson.

Monohon returned to Renton about once a year during his dozen years in the Far North. He built a cottage at 62 Logan Street around 1900 and, once he returned to Renton for good in 1909, lived there until his death in 1951. He never married. His mother lived with him in his Renton home(s) for 25 years until her death in 1912; later his sister Emma lived with him for many years. Toward the end of his life his niece, Charlotte DeMars, moved in with him.

Monohon continued his work as a civil engineer when he returned to Renton in 1909. In 1911, the Cedar River flooded Renton. Monohon energetically lobbied the King County Board of Commissioners to appropriate $50,000 to dredge the river and divert its waters so they no longer emptied into the Black River, thereby eliminating the flooding problem that had plagued Renton’s city center since its earliest days. This was accomplished in 1912 when a 2,000-foot long, 80-foot wide canal was dug, channeling the Cedar River so that it no longer flowed into the Black River but instead flowed north into Lake Washington. This success resulted in Monohon being appointed as an engineer in charge of dredges for a number of years.

Good Roads

But Monohon is most remembered for his work with the Washington State Good Roads Association. In the 1890s there was only thin scattering of wagon roads in the state. Roads (usually just graded dirt tracks) were built only within a county or a road district, with a road supervisor in charge of construction. There was no coordination between the counties or districts as to how their roads might connect with one another, which resulted in a number of roads to nowhere that had little lasting value.

In December 1896 the first Good Highways Convention met at the Seattle Chamber of Commerce to promote better roads in the state and to come up with a new, improved system of road building. Monohon was there, and was a forceful voice arguing for change. He called the road supervisor system "rotten to the core, not on account of the character of the men involved, but from the inherent vices of the system"("Good Highways Convention meets ..."). This meeting led to the formation of the Washington State Good Roads Association three years later.

The Washington State Good Roads Association was organized in September 1899 at a meeting in Spokane led by Seattle businessman Sam Hill (1857-1931). Hill invited 100 men to the meeting to discuss ideas to improve the state's highways, but only 14 came. Monohon (who took a break from his work in the Far North to attend) was one of them. As the twentieth century got underway, these 14 charter members lobbied the state legislature tirelessly to centralize a state highway system built and maintained by state officers, as opposed to the uncoordinated work carried on by various county commissioners in Washington state's 39 counties. In 1905 the state legislature created a state highway board, which eventually led to the formation of the Department of Highways (later the Washington State Department of Transportation).

Monohon played an active role in the Good Roads Association during the 1910s, particularly later in the decade, as the automobile became more widespread. By the end of the 1910s it was becoming obvious that it would be necessary to build a nationwide system of highways to provide access for the automobile and to connect the country. The question then arose how to pay for it.

Early roads had been funded by property taxes, special levies, and individual assessments. But in a 1948 Seattle Post-Intelligencer interview, Monohon explained that at the Good Roads Association convention in 1919 there was considerable pressure for approval of a $30 million bond issue to build roads. Monohon, chairman of the resolutions committee that year, vigorously argued against it, saying that the State could not afford it. Voters rejected such a bond issue in 1922, and during widespread road construction in the state during the 1920s, roads were built and maintained with motor vehicle licensing fees and gasoline taxes. "My biggest victory, and the thing I'm proudest of, is my part in keeping the Washington [state] highway system out of debt," Monohon said in the 1948 P-I interview.

Last Years

Monohon takes the honors of being the last surviving charter member of the Washington State Good Roads Association, which is now named the Washington State Good Roads and Transportation Association. But he was active in his community too. Described as “progressive ... in his political views” (Hanford, p.223), he served on the Renton City Council for eight years, was a lifetime member of the Renton Chamber of Commerce, and was an active member of the King County Pioneers Association. He was also an active Mason for more than 40 years.

He remained physically and mentally active well into his 90s. Not long after his 93rd birthday he fell ill. He died six weeks later, on July 29, 1951.