On April 2, 1910, Charles Keeney Hamilton (1885-1914) of New Britain, Connecticut, is the first aviator to demonstrate airplane flight in Spokane. The exhibition, held at the Spokane Fairgrounds, is part of a nationwide tour sponsored by aviation pioneer and airplane manufacturer Glenn Hammond Curtiss (1878-1930). The chief local booster and organizer of the three-day Spokane air show is Polish immigrant Harry Green (1863-1910), a prominent businessman and sports and entertainment promoter.

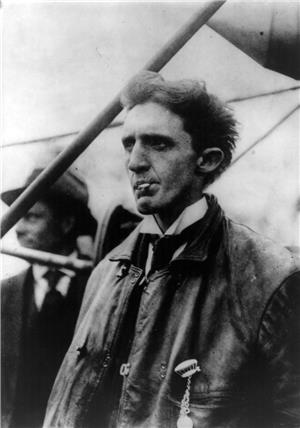

Daredevil Flyer

Hamilton was already a hot air balloonist, dirigible pilot, and parachute jumper when he began flying lessons in 1909 under Glenn Curtiss himself. Within six months he had become perhaps the best-known daredevil flyer in the United States.

His visit to Spokane was on April 1-3 after he had done a similar demonstration on March 11-13 at Meadows Race Track just south of Seattle near present Boeing Field. The Seattle demonstration was the first air flight to occur in Washington state. Telegrams made public later revealed that Curtiss claimed his company lost money on the Seattle and Spokane visits. He had wanted Hamilton to cancel them in favor of more lucrative offers from other cities, but Hamilton refused.

Crowds through the United States flocked to watch pilots perform such stunts as climbing to some 1,500 feet, cutting the engine, diving and restarting the engine at the last moment. Aviators could earn as much as $10,000 for two or three flights, but many were killed in the attempt. Hamilton was especially successful at performing this stunt.

Thrilling the Crowds

April 1, the first day of Hamilton’s Spokane demonstration, was a failure, as he could not start the engine of his Curtiss biplane. During the next day he made several successful flights to and from the fairgrounds, thrilling the crowds with his antics. The Spokesman-Review of April 3 describes his performance of the previous day. During his second flight,

“ ... the aviator was forced about a mile and a half east of the fairgrounds where he circled over the houses before being able to get back over the grandstand. While east of the grounds, Hamilton found a high-power, 12,000-volt electric line in his path. Being unable to rise sufficiently to pass over it, he let his machine run a few feet above a street, passing below the wires and between the poles, he ran along the road for quite a little distance before being able to get above the wires and in the clear sufficiently to soar” (McGoldrick, 6).

That same day, Hamilton boasted, “I can take the hat off your head if you want me to, for I can fly any height above the ground” (McGoldrick, 6).

Mechanical Challenges and More Thrills

Those early aviators had to be resourceful mechanics as well as flyers. In preparing for the next day’s flight, Hamilton worked late into the night trying in vain to repair a damaged magneto. He tried to persuade Harry Green to sell him his car for $3,500 in order to get a magneto. Green refused, but Hamilton was able to buy another car to get a six-cylinder magneto to adapt for his eight-cylinder engine.

The third day of Hamilton’s exhibition drew a crowd of 20,000, although only 3,000 had paid admission. In addition to the crowd at the fairgrounds, the newspaper reported that many watched "from roofs of houses and factories, in tree tops and on telephone pole cross pieces" (McGoldrick, 7).

Harry Green died of pneumonia on December 14, 1910, soon after the historic flight exhibition he had promoted. Thus, he did not live to see the subsequent flourishing of aviation in Spokane.