Washington Territory’s De Tocqueville is an apt description for Father Louis Rossi, a Catholic missionary priest who ministered for just over three years, from 1856 to 1860 in Washington Territory and then for almost three more years in Northern California. He returned to Europe in 1862 and the following year, at the urging of friends, published in French a memoir of his experiences. In 1983 it was translated and annotated by W. Victor Wortley (d. 2008), then a professor in the Department of Romance Languages and Literature at the University of Washington.

From Ferrara to Fort Vancouver

Rossi was born Abramo De Rossi in 1817 in Ferrara, Italy, to Jewish parents. At 18 he became a Catholic and at baptism, as was customary, changed his name to Luigi Angelo Maria Rossi. Two years later he was accepted as a seminarian in a very strict order of missionary priests known as The Passionists. In a matter of months he was asked to leave and the documents pertaining to his dismissal record that he was “petulant and choleric” (Wortley, 10-11). Perhaps his threat to strike his novice master with a large altar candle had something to do with it. However he was reaccepted and in April 1843, at the age of 27, was ordained a Passionist priest. After teaching rhetoric and philosophy for several years, Rossi spent six months learning to speak French and in January 1855 was selected to be the superior of a Passionist community in Bordeaux, France. Almost immediately, it appears, interpersonal problems erupted and in October Rossi was asked to resign his position. Perhaps in a display of petulance and choler, he opted instead to resign from the Passionist order and became a secular priest.

The following summer of 1856 Rossi journeyed to Brussels to meet with Montreal-born Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet who was in Europe to raise money and to recruit missionaries for the Diocese of Nesqually, which he administered from his three room home located adjacent to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. (In recognition of the burgeoning population on Puget Sound, 47 years later the seat of diocesan government was moved and in 1907 was renamed the Diocese of Seattle.) Rossi was immediately accepted and in November 1856 the two landed in Montreal where the Bishop -- with Rossi’s help -- recruited five Sisters of Charity of Providence, including the redoubtable Mother Joseph (1823-1902), who established some 29 schools, hospitals, and orphanages before she died in 1902.

Upon arrival at Fort Vancouver in December 1856, he was immediately put to work learning English -- for the first time -- while performing as the Bishop’s secretary and clerical “gofer.” At some point prior to this, Rossi had begun referring to himself as Louis rather than Luigi. In November 1857 Blanchet assigned him to minister to the 300 Catholics in an area which ranged from the Cowlitz River on the south to the Canadian border and from the Cascade Mountains to the Pacific. His written instructions direction that “The whites will be specially the object of your pastoral solicitude, the Reverend Oblate Fathers being specially charged to evangelize the savages” (Wortley, 354). Blanchet is referring to the priests and brothers of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who in June 1848 established the St. Joseph of Newmarket mission at what is now Priest Point in Olympia.

It may be just as well that Rossi’s responsibilities did not include the Indians, as his Eurocentrist sense of superiority towards these “sauvages” conflicted with his spiritual obligation to treat all men equally as children of God. He did however think more highly of the Indians in California and elsewhere a number of whom had learned to read and write in mission schools. To him, the ability to read and write were measures of intelligence.

Ministering to Fort Steilacoom

Rossi selected Fort Steilacoom as the base for his ministry because of the large number of Irish and German Catholics found among the soldiers and also because they, along with a handful of families from nearby Steilacoom, had built a chapel in the middle of the fort. Another motive may well have been the presence of the army doctor, who could treat him for his frequent bouts of severe pain in the abdomen, chest, and joints. (It is likely that Rossi was afflicted with Mediterranean Familial Fever, an inherited disorder to which Sephardic Jews are particularly prone. The malady manifests itself in recurrent severe stomach cramps and chest and joint pains, accompanied by a high fever. Rossi was twice subjected to operations in an apparent attempt to cure him: first by the heavy-drinking surgeon at Fort Steilacoom, who may have removed his appendix, and then by a father-son team of physicians in San Francisco, who possibly removed his gall bladder. They offered to show him what they had extracted but he, understandably, declined.)

As there were virtually no roads and few passable trails, Rossi made the rounds of his missionary district occasionally on horseback but mostly in Indian canoes and on the several paddle and screw steamers that plied the sound. He was constantly on the move and became a familiar and recognizable sight in his black robe and wide European hat. His ministrations were available to Catholic and Protestant alike and he noted -- with modest self-satisfaction -- that the latter typically made up half or more of his congregations and audiences and accounted for a commensurate portion of the funds put in the collection plate.

Mills and camps rushed into existence by the demand for lumber from California’s gold fields offered fruitful opportunities for his ministry and by Rossi’s count he visited some two dozen of them scattered in isolated nooks and crannies from Olympia to Port Townsend. On a visit to Seattle in July 1858 he lodged in the infamous Felker House hotel run by Mary Conklin (1821-1873), known locally as Mother Damnable for her foul tongue and bullying ways. In her drawing room he preached a sermon to an audience that remained silent when he exhorted them to join him in prayer because, as he learned later, there were no Catholics in the room. And apparently, on that occasion at least, there was none in the entire village.

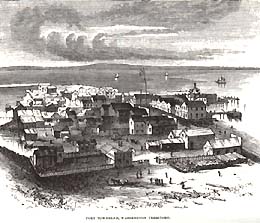

In 1858 Rossi moved to Port Townsend, because “around Port Townsend there are many localities I must minister to. [It] is more central than Steilacoom. Moreover, in case of need, the faithful in Steilacoom and Olympia can easily avail themselves of the Oblates ... . All these reasons, added to the opportunity of building a church in Port Townsend, induced me to transfer my residence there” (Wortley, 168-169).

But Rossi’s ailments continued to plague him and he repeatedly beseeched Bishop Blanchet to relieve him of his responsibilities and let him return to Europe to recuperate. Finally, not long after Rossi ministered to the soldiers on San Juan Island during the Pig War, Blanchet capitulated and in January, 1860 Rossi sailed for San Francisco, the first stop on his journey home. A journey that was to take much longer than expected because, as Rossi noted, “Man proposes, God Disposes” (Wortley, 223).

California Legacy

While waiting for a ship to take him on the second leg, to Panama, he enjoyed the warm hospitality of the first bishop of the San Francisco See, Spanish-born Joseph Sadoc Alemany. In a city where shanghaiing sailors was somewhat of an art form, the Bishop caused poor Father Rossi to be shanghaied with all the effectiveness of a press gang, albeit gently of course, and with the loftiest of spiritual intent. As Rossi noted, “Several of my colleagues remonstrated with me urgently, pointing out, particularly, that the number of evangelical workers in the region was very small for the cultivation of such a vast territory” (Wortley, 223). In March 1860 he found himself responsible for yet another huge missionary territory which stretched some 240 miles from Santa Rosa to Crescent City, California.

Still afflicted with his debilitating bouts of pain, in 1862 he finally prevailed upon Bishop Alemany to let him return to Europe once and for all. This time he made it and arrived back in Brussels, Belgium, on November 19, 1862. He left behind the four churches he built in California at Bodega, Tomales, Healdsburg, and Santa Rosa, along with one he built in Port Townsend and one that he finished in Olympia. Only two of the six buildings still exist, in Bodega and Tomales; both are active Catholic churches.

Back in Europe

Not long after arriving back in Europe, at the pleading of friends, he began writing his memoir which was published in 1863 under the title Six Years in America, California and Oregon. In 1864 a second edition was entitled Recollections of a Voyage in Oregon and in California. Both titles apparently allude to the fact that Washington Territory had earlier been part of the Territory of Oregon, but they’re misleading in that his only service in Oregon Territory was for a brief period while he was learning English from an Irish missionary in Portland.

As he had not intended to write a memoir, his recollections were unsupported by notes and occasionally marred by a faulty memory. Nevertheless it is a remarkable document that deserves study by any student of mid-nineteenth century United States history and of Washington and California in particular. The wealth of detail about national and regional politics, attitudes leading up to the civil war, secret societies, Protestant revival practices, local politicians, etc. indicated he must have spent a considerable amount of time just asking questions and seeking opinions. And it is replete with references to his affection for America and Americans, noting “All those who know America, love it. Indeed, how would it be possible not to love such a liberal country” (Recollections).

Professor Wortley noted in his introduction that “Louis Rossi is not exactly a prototypical Catholic Missionary priest” (Recollections). How true! In his memoir Rossi made a compelling, albeit unexpected, case for his strong support of the separation of church and state. “I share the opinion of those who say that as long as America doesn’t come under the influence of any particular religious faith, she will be not only free, but she will free others” (Recollections). Also, as a missionary he made no great effort to convert people to Catholicism, feeling that if his fellow pioneers here on the frontier lived a virtuous life according to their own beliefs, that was sufficiently meritorious for eternal salvation. However he did fret about being an “unworthy” priest because he hadn’t made more of an effort to garner converts.

Father Louis Rossi died on September 9, 1871. He is buried in a cemetery in Ile Ste. Denis in Paris.

He needn’t have worried about being unworthy. He left behind a legion of warm friends and admirers who were impressed both with him and with his representation of Catholicism. Upon learning of his impending departure from Puget Sound, the non-Catholic publisher of Steilacoom’s Puget Sound Herald, Thomas Prosch, wrote:

“The departure of Father Rossi will be a source of regret throughout the Sound. His amiable manners, his kindness of heart, and his zealous endeavors to promote the moral and spiritual welfare of the people have gained him the esteem and confidence of all. Coming, as he did, among a population composed of but few Catholics, he has succeeded to a wonder extent in doing away with the prejudices which most Protestants entertain against the Roman Church.; and by his sermons, his lectures, and the purity of his private life, he has exerted an influence on our community that will be felt long after he has left us” (Wortley, 159).

A few months earlier, ethnographer James G. Swan (1818-1900), also a non-Catholic, had written a lengthy article for the San Francisco Evening Bulletin extolling the many virtues and benefits of taking up residence in Port Townsend, among these he included the presence of Fr. Rossi. “(He) is an intelligent and highly educated gentleman, with whom it is a pleasure to converse. He is an Italian by birth, and his gentlemanly and agreeable manners have already won him many friends, even among the Protestant portion of the community” (Swan, 14).

High praise for a missionary who worried whether he had done enough to accomplish his mission.