Jerzy Friedrich was a Seattle resident who arrived in the Pacific Northwest in 1959. He was born in Lwow, Poland, in 1920, and his life intersected with the ravages and traumas of World War II in Europe. In 1939 Germany and then the Soviet Union invaded his country. In 1940 Friedrich was deported to the Soviet Union, where he worked on a collective farm. In 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union, and subsequently Poles in the Soviet Union were allowed to fight the Germans. Friedrich joined that army and eventually became an officer. He left the Soviet Union in 1942, fought in Italy for a year, and after the war remained in Italy. He married and started a family, moved to Argentina in 1948, and to Seattle in 1959. In 2008, HistoryLink.org historian Phil Dougherty interviewed Mr. Friedrich at length. This People's History is presented as the life and long journey of one Seattleite from Poland to the Pacific Northwest.

Beginnings

Jerzy (pronounced Yher-zay) M. Friedrich was born in Lwow, Poland, on January 18, 1920. In 1920, Lwow (pronounced Le-voof) was in southeastern Poland, but became part of Russia’s Ukraine after borders were redrawn at the end of World War II. The city is located about 250 miles southeast of Warsaw, the Polish capital. His father abandoned the family when Friedrich was 2, and he and his mother moved in with her parents. His childhood was not particularly happy -- he missed having a father -- but both his father’s parents and his mother’s parents helped support him and his mother, and they lived comfortably: He and his mother lived in a separate house on his maternal grandparents' lot. His aunt, uncle, and two cousins lived in still another house on the grandparents' property. They had a maid. And he was particularly fortunate to get a good education, which would serve him well in the adventures that awaited him as a young man.

In the summer of 1939 Friedrich -- nicknamed Jurek (pronounced Ou-rick) by his family and friends -- was pursuing his studies in math and physics at liccum, the Polish equivalent of technical college preparatory. War talk was in the air, and “I followed it closely,” he said. “But I didn’t think war would start. I was a kid and I was stupid to think that the Germans would respect the non-aggression pact [that it had entered into with Poland in 1934]. And I was a chauvinist -- I knew as a 19-year-old I’d be involved one way or another. But I was absolutely not scared. We believed England and France would support us if Germany invaded, and I didn’t believe Hitler was stupid enough to start war with England and France. My relatives did not share in my opinion.”

War and Occupation

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. “We got up, turned on the radio and heard the Germans had crossed the border in numerous places in the west. The announcer began reading numbers -- we didn’t know what they meant, but they were a code calling military units up. Then, about 11 a.m., I heard planes outside and ran up to the roof. German Stukas were diving where I knew the railroad station was. I couldn’t see if they hit it, but I could see the explosions. I went in to lunch and told my mother and grandparents what I had seen. My grandfather said ‘You are talking stupidly. Nobody has declared war on Poland. You are almost a man and you are spreading gossip like an old woman.’ I started to tell him again -- but a look from my mother and grandmother shut me up. We finished our lunch in complete silence -- not one word.”

The Germans bombed Lwow indiscriminately for several weeks. The city had no major industrial targets but, with a population of about 300,000 in 1939, was a transportation hub. Friedrich was willing to fight and tried to volunteer, but was told he wasn’t needed -- Poland lacked sufficient arms to provide its troops, and the Germans were moving too fast for the Polish military to mount an effective response. So he waited, believing the propaganda that the intervention of England and France would stop the German invasion. “By September 15 we were accustomed to the bombs,” he said. “But then one day we were sitting on our front doorstep and we heard machine guns. The Germans had come up from Czechoslovakia [south of Lwow], and before I knew it they were within a kilometer of our house.” Then, on September 17, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east. “A few nights later I was out on the street alone. We were in a blackout, but the sky was lit up from fires, Germans on one side, Russians on the other. For the first time I realized we were going to lose the war. The surrender was the worst part of my life.”

Warsaw surrendered on September 27, 1939. Lwow’s local commander negotiated a surrender with the Russians, who by then had already occupied the city. Other parts of Poland were occupied by Germany. Friedrich soon learned the Russians and Germans had different systems: Germans would come in during the day and drag groups of citizens screaming from their homes (although he never saw this firsthand, since the Germans did not occupy Lwow when he was there). The Russians were stealthier. Friedrich explained, “You never saw Russian soldiers in the street. But you saw political officers in the street, and they talked to us: ‘See, we are not your enemy. We are Slavs like you.’ But then in the night, people would disappear.”

Deported

Despite the Soviet occupation, Friedrich was allowed to continue his studies. By Christmas 1939 the Russians had taken over his grandparents' house, and the entire family moved into his aunt’s house. Then, in February 1940, the family learned a large transport of Poles had been shipped to the Soviet Union. Their dread grew that they would be next, and they were right. On April 10, a neighbor came by and warned them that another transport was going out, and they were on the list. “I could have run away,” said Friedrich. “But these are terrible decisions to have to make, to run away and leave your family behind. I didn’t do it.” Half an hour later, the Russians knocked on their door. They then entered with guns drawn.

The Soviets took away Friedrich’s 84-year-old grandfather that night, and the family never saw him again. Three nights later, on April 13, they came back for the rest of the family. The family was given half an hour to pack, and was then taken to the railroad station and loaded onto a boxcar with perhaps 60 other people. The Soviets had built two shelves inside the boxcar, making three areas for people to sit. The top shelf was big enough to sit in; the middle shelf was big enough for a person to lie down (older people got these spaces) and the bottom section, along the floor, was just big enough to crouch in. This is where Friedrich rode. The toilet was a rough dirty board with a hole cut in it, placed across a four-inch gap in the door; “This was the worst part of the whole trip,” Friedrich said.

For more than 17 days the train rode east, across the border into the Soviet Union, east through Kiev and across southern Russia, on and on, in a roundabout route that eventually stretched more than 4,000 miles. The train stopped once a day, usually around noon, where two men (Friedrich was often one of them) were allowed to get off and take food back to the rest of the prisoners. Friedrich’s education began paying off: “Even though the signs were in Cyrillic, I could read them. I knew where we were.” When the train finally stopped for good on May 1 in Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan, they were only 300 miles from the border of China.

The Collective Farm

Friedrich and his family were transported about 20 miles from Semipalatinsk to a collective farm, or a kokholzy, (pronounced ko-hos) where they were allowed to pick a single room in one of the local’s homes to live in. They found a house occupied by a relatively small family, but it was “primitive conditions,” scowled Friedrich. “Not even an outhouse.” He plowed with oxen during the day, earning enough food to feed his family. In an odd twist, Friedrich explained, they were “special transports,” and technically not prisoners -- they had freedom to move about the farm or go to the city if they asked permission.

But they were barely a step above being prisoners. “I was a slave,” he said. “We were only given the barest necessities to survive. And if you couldn’t work, you starved to death. If you needed something, you pretty much had to steal it. I didn’t know how I was going to survive. But you manage -- you always manage.” Escape was theoretically possible -- but where would have they have gone?

Several thousand people were on the 30,000-hectare farm, and over time, Friedrich came to recognize most of them. He was able to follow the war’s progress on the radio and in newspapers, although the Russians controlled the flow of news and thus he knew only broad outlines: The German sweep across Europe in the spring and summer of 1940, France’s sudden collapse, Great Britain seemingly the next domino about to fall -- “This was a DISASTER,” he emphasized. “I was petrified. But I was young and still optimistic. We were miserable -- but we had to live.”

After nearly a year at the kokholzy, the family was transferred to Semipalatinsk. Friedrich, his mother, and his grandmother found what in essence was a freestanding bathhouse and settled in. The building was about 50 years old, built from ax-cut logs, and with a concrete floor. There was enough room in the one-room structure for a kettle and stove and for them to sleep in; Friedrich fashioned a bed out of boxes. There was no running water or indoor plumbing. If he wanted a bath, he paid two rubles for one at a nearby public bathhouse. He went to work remodeling buildings, though he wasn’t paid enough to live on, and was (like most of the population) forced to troll small flea markets to try to obtain what he needed. He had been living in Semipalatinsk for only a few months when the Germans turned on their Russian allies and invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

Turnaround

He broke into an excited smile when asked about that day. “We were in park, a converted cemetery actually, in the middle of town. Some of the houses around the park were mounted with radio speakers that usually played music or government propaganda. Suddenly the speakers announced Germany had invaded Russia, and Stalin came on and began speaking. The Russians were stunned. They sat there for a minute, then silently stood while Stalin spoke. We Poles couldn’t say a word, but we looked at each other with grins and nudges. We knew something would happen.”

And happen it did. From that day forward, they were allies with the Russians. The Russians changed the Poles’ documents to reflect their newly elevated status, which entitled them to better opportunities. The Russians became more free with the news. Everything changed. “Suddenly they became very sweet,” explained Friedrich, “because even in Semipalatinsk you could feel Moscow shaking. The Germans were advancing on Moscow. I thought they would take it. Then a Polish army was allowed to form in Russia, and suddenly, I was free.”

Becoming a Soldier

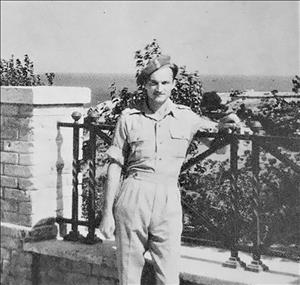

It was March 1942. “As a man, I knew I had to fight, but I felt badly leaving my family behind,” he said. He traveled west across Kazakhstan to the Caspian Sea, took a boat to Iran, crossed northern Iran, Iraq, and went to Palestine (now Israel). He patrolled the beaches with the British, who feared the Germans were going to invade Palestine. But by early 1943 the tide of the war was turning against Germany, and the pressure on Palestine lessened. Meanwhile, Friedrich had spotted an opportunity and applied for Officer School. He was accepted, and in April 1943 reported to class at the British Royal Air Force base at Habbaniya, about 55 miles west of Baghdad, Iraq. “Nothing but desert,” he summarized. In October he graduated as a cadet officer, which, in the Polish Army, did not mean you were an officer, but a candidate to become one. (He eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant.) But even as a cadet he had the same privileges as an officer, and was treated as one.

But there was another episode that made Habbaniya memorable for him. He had been out of touch with his family for more than a year by this time, and had no idea where they were or how to reach them. The officer’s club at Habbaniya was set up in a large tent, and one day Friedrich noticed a large, new American-made car parked in front of it. It was such a novelty that he walked up to the car to check it out. He saw the driver was in a Polish uniform and struck up a conversation with him, and mentioned that he had been at Semipalatinsk. The soldier told him he had recently been in Tehran, Iran, and there was a refugee camp there; the solider specifically mentioned that he thought some of the female refugees at the camp were from Semipalatinsk. Friedrich wrote the camp commander, identified his family, and asked for any information available. Two weeks later, he heard from his older cousin, Zygmunta, who was at the camp. He learned that his mother and grandmother had been sent to a refugee camp near Kampala in Uganda, Africa. From then on, he was able to keep in touch with his family.

Combat

After graduating from Officer School, Friedrich briefly returned to Palestine. But by the end of 1943 he was in Naples, Italy, which American forces had recently liberated. He trained his army, went briefly across Italy to the city of Bari on Italy’s southeastern coast, then returned to western Italy to fight at Monte Cassino during the early months of 1944.

Friedrich was in the Third Infantry Division of the Second Polish Corps, which was part of the British Eighth Army. His knowledge of math and physics landed him in the light artillery division. He explained, “I was in the artillery, so I was always back. I never engaged in hand to hand fighting or machine gun fighting. I did not climb the hill at Monte Cassino, but after the battle, I was awarded the Monte Cassino Cross. I was ashamed. How could I compare myself to all the people who went up the hill? They were the heroes.”

He may not have climbed the hill, but he had his own intense moments when death was millimeters away. One day he was in a long column “as far as the eye could see” of men, truck, and material, all on an open road. Unexpectedly the Germans began shelling. There was nowhere for the soldiers to go. Described Friedrich, “I could hear shells landing behind me and thinking ‘that’s my men they’re hitting.’ I was riding in a truck loaded with benzene, and I knew if we were hit we would explode. It is holy terror when you have to take it and cannot defend yourself. But I had to be calm for my men. To break yourself to be calm is real courage, because you are terrified -- especially the better educated you are, because you know what might happen. Courage is to control terror, especially when you can do nothing to fight it.”

The battle of Monte Cassino ended in May 1944. Friedrich’s unit returned to eastern Italy, and over the course of most of the next year fought its way 200 miles north along the eastern flank of Italy from Ortona to Bologna. “Since I was in the artillery, we almost never saw the death and bodies even though artillery caused 60 percent of it. By the time our units advanced, the infantry had cleaned up and the bodies were gone. But one day we advanced so fast I saw four dead German soldiers. This is rude to say, but I felt a satisfaction, a job well done. This is what war makes you -- it transforms you from a civilian to a killer.”

Searching For Home

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945. Friedrich was in Bologna, along with units of British and American armies. “The Poles entered Bologna first,” he noted, laughing, “we were more macho.” Days later, the news of Germany’s unconditional surrender was announced. “The British and Americans started shooting off all of their ammo,” he said. “The skies were full of rockets. They got drunk, they were happy -- they were going home, though of course they still had to fight the Japanese. But in our [Polish] sector, there was silence. We were astonished. [As part of the Yalta accord] Roosevelt had given my part of Poland to the Russians. I had no home to go to. It was an enormous tragedy; you cannot imagine. I had become used to advancing five kilometers at a time, getting closer to home. But just before the war ended I found out I had no home to go to. I had no money, no citizenship, no documents. I was deeply depressed and disappointed.”

After the war he remained in Bologna for a time, then in March 1946 went to Turin, Italy, to attend polytechnic school. He soon met his wife, Pia (1923-2007), and they were married that October; they had two children, Vivian (b. 1947) and Alexander (b. 1950). He continued his studies in Turin and was happy there -- but then, in 1948, Italy had its first election since war’s end to elect a government. It was a particularly heated election, with the United States heavily influencing one side and the Soviet Union the other. “I panicked,” said Friedrich flatly. “I thought the communists would win and we would be deported again, so we decided to leave. But the communists lost. Ach! Had I known, I would have stayed in Italy.” He was unable to get approval from the United States to immigrate to this country, and Europe was flooded with refugees. But Argentina was accepting refugees, and in March 1948, the month before the election, the Friedrich family traveled to Buenos Aires.

They would remain in Argentina for 11 years. Life in yet another new country was difficult, but over time they became acclimated and eventually prospered. In the meantime, Friedrich remained in touch with his family. In Tehran his cousin Zygmunta had met and married an American soldier from Seattle, and they had come to Seattle after the war. A few years later her parents had also moved to Seattle. They encouraged Friedrich to move to Seattle, and explained there were far more opportunities here.

After a few years in Argentina, he began making applications to move to America. It took seven years, but his applications were finally accepted by the U.S. government, and the Friedrichs -- including his mother, who had joined them in Argentina -- arrived in the United States on February 14, 1959. They moved to Seattle and settled in the Sandpoint neighborhood. Friedrich worked as a draftsman for various companies for a number of years, then concluded his career with an 18-year stint as an associate architect at the University of Washington, Division of Facilities Planning and Construction.

Looking Back

Friedrich first returned to Poland, accompanied by his wife and now-grown children, in 1969. He recalled, “We drove north from Czechoslovakia, driving a brand-new Mercedes-Benz. We came up on the border checkpoint, and I saw the Polish flag and Polish soldiers. I stopped at the checkpoint -- and I choked up.” Here he paused briefly in his narrative, and his eyes brimmed with tears. It was a powerfully moving moment. He quickly explained, “It is still hard to compose myself when I think of the first time I saw the Polish flag and Polish soldiers. After 30 years I was coming home. It was a moment I’ll never forget.”

He concluded, “After 70 years, I don’t know if we did the right thing by fighting back when the Germans invaded. We were determined not to give up like the Czechs [who had surrendered to the Germans without a fight six months earlier], but Czechoslovakia was not destroyed as parts of Poland were, and thousands of people, like me, never came back. This was a loss for Poland -- I came here and got a good education and was successful. But I would have been successful there. It’s an emotional question.”