On the night of March 20, 1975, a U.S. Air Force C-141A Starlifter, returning to McChord Air Force Base from the Philippines via Japan with 16 servicemen aboard, is flying southbound over the Olympic Mountains. A Federal Aviation Administration air traffic controller, nearing the end of his shift, mistakes the Starlifter for a northbound Navy A-6 Intruder, on approach to Whidby Island Naval Air Station, and directs the pilot to drop altitude to 5,000 feet. Complying with the incorrect order, the C-141A crashes into Warrior Peak on the northwest face of Inner Mount Constance in the Olympic National Park, killing all onboard. Attempts are made to recover victims, but due to inclement weather and dangerous snow conditions, 15 of them will not be recovered until springtime. In terms of loss of life, it is the biggest tragedy ever to occur in the Olympic Mountains.

The Aircraft

The Lockheed C-141A Starlifter was introduced in 1963 to replace slower propeller-driven cargo planes such as the Douglas-C-124A Globemaster II. It was the first jet specifically designed for the military as a strategic, all-purpose transport aircraft. The Starlifter, a large aircraft, 145 feet long with a 160-foot wingspan, was powered by four Pratt & Whitney jet engines. Its shoulder-mounted wings and rear clamshell-type loading doors gave easy access to an unobstructed cargo hold, measuring nine feet high, 10 feet wide and 70 feet long.

At a cruising speed of 566 m.p.h., the plane was capable of carrying more than 30 tons of cargo approximately 2,170 miles without refueling. When configured for passengers, the C-141A could accommodate 138 passengers.

On Thursday, March 20, 1975, U. S. Air Force C-141A, No. 64-0641, under the command of First Lieutenant Earl R. Evans, 62nd Airlift Wing, was returning to McChord Air Force Base (AFB) from Clark AFB, Philippines, with en route stops at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, and Yokota Air Base, Japan. The plane was due to arrive at McChord at 11:15 p.m. Flown by the Air Force Military Airlift Command (MAC), Starlifters normally carried a six-man crew consisting of two pilots, two flight engineers, one navigator, and one loadmaster. But on March 20, because of a grueling, 20-hour flight from the Philippine Islands, the C-141A was carrying four extra relief crew members. In addition, the plane was transporting six U.S. Navy sailors as passengers, heading to new ship assignments.

The Mishap

At 10:45 p.m., while over the Olympic Peninsula, approximately 90 miles from McChord AFB, the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) Seattle Air Traffic Control (ATC) Center gave the pilot clearance to descend from Flight Level 370 to 15,000 feet. Several minutes later, approach control at Seattle Center cleared the plane to descend to 10,000 feet.

The last radio message was received at approximately 11:00 p.m. when the pilot acknowledged authorization from approach control to descend to 5,000 feet. Five minutes later, the C-141A disappeared from the radar screen.

Attempts to Search and Rescue

Besides being nighttime, weather conditions in the Puget Sound area were extreme, with high winds, snow, freezing rain, a low cloud cover, and a only a quarter-mile visibility. McChord immediately put rescue helicopters and an Air Force Disaster Preparedness Team on alert, awaiting break in the weather. Coast Guard Air Station, Port Angeles, became base-of-operations for the impending search-and-rescue effort. Shortly after the plane’s disappearance, some 120 mountaineers from the Seattle, Everett, Tacoma, and Olympic Mountain Rescue Units and several military helicopters assembled there, awaiting orders.

At 2:45 a.m. on Friday, an Air Force Lockheed C-130 Hercules from McClellan AFB, California, flying at 30,000 feet, reported a rough “fix” on the Starlifter’s crash-locator beacon, in the mountains approximately 12 miles southwest of Quilcene in Jefferson County. Ground parties were flown by helicopter to Quilcene, prepared to hike to the crash site, but they needed the location pinpointed because of the rugged terrain and winter weather. Lieutenant Robert Herold, a helicopter pilot from Coast Guard Air Station, Port Angeles, established the exact location of the signal by triangulation several hours before weather allowed the wreckage to be spotted from the air. It had crashed into the northwest face of Mount Constance (7,756 feet), just inside the eastern border of Olympic National Park.

Bad weather continued to plague aerial search operations throughout Friday. Finally, at about 4:20 p.m., after searching sporadically for eight hours, an Army Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopter from Fort Lewis spotted the wreckage. The pilot, Warrant Officer Edward G. Cleves, and his observer, U.S. Forest Service Ranger Kenneth White, reported the plane appeared to have impacted at about the 6,000-foot level of jagged Warrior Peak (7,310 feet), then slid down the mountainside. They reported seeing the tail section, a large piece of the fuselage and part of a wing at the 5,000-foot level in a canyon above Home Lake, the headwaters of the Dungeness River, and debris scattered over a wide area on the steep slope. The helicopter made three passes over the area, but neither Cleves nor White spotted any bodies or signs of life. Because there were deep fractures in the snow above the wreckage, White reckoned an avalanche would soon bury the crash site until spring.

On Saturday morning there was a break in the weather. Army helicopters dropped explosive charges at various locations on the steep slopes surrounding the wreckage to diminish the avalanche hazard. Then, two Army Boeing-Vertol CH-47 Chinook helicopters ferried several rescue teams onto the mountain to search the ridges and ravines for possible survivors. They were also hoping to find the aircraft’s flight data recorder, which might provide clues to the cause of the crash, but much of the wreckage and debris had already been covered by snowfall. Forced out by a new storm, the searchers left the site that afternoon without finding any bodies on the mountainside.

On Sunday and Monday, poor flying conditions in the Olympics hampered efforts to search the Mount Constance crash site for survivors and the flight data recorder. Mountain-rescue experts conceded, however, there was no doubt all 16 persons aboard the Starlifter were dead.

A Regrettable Human Error

Meanwhile, at McChord AFB, an investigations board, consisting of eight Air Force officers and four National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) officials, headed by Major General Ralph Saunders, was convened to determine the official cause of the tragedy. Of particular interest were radio communications between the C-141A and Seattle Center, minutes before the crash.

On Monday morning, March 24, the FAA announced that a “regrettable human error” by a Seattle Center air traffic controller was believed responsible for the loss of the Starlifter. Tape recordings of the radio transmissions revealed that the controller had confused the southbound Air Force C-141A with a northbound Navy A-6 Intruder that had been flying at the same altitude, en route from Pendleton, Oregon, to Whidby Island Naval Air Station. The controller intended to instruct “Navy 28323” to descend from 10,000 feet to 5,000 feet, but inadvertently gave the order to “MAC 40641,” flying over the Olympic Mountains. The Starlifter’s pilot responded: “Five thousand -- four zero six four one is out of 10.” Still approximately 60 miles northwest of McChord AFB, the pilot started to descend and struck a ridge near the top of Mount Constance. The error was discovered when the tapes were played, an hour after Starlifter had gone missing. The controller, in a state-of-shock, was relieved of his duties and placed under a doctor’s care.

Finding the First Body

Meanwhile, a 10-man search team from Olympic Mountain Rescue (OMR) and the National Park Service, airlifted to the crash site, discovered the forward fuselage section and the remains of Lieutenant Colonel Richard B. Thornton, the aircraft’s navigator, while searching at about 7,000 feet, well above the suspected impact level. Late in the afternoon, David W. Sicks, team leader and OMR’s chairman, decided to abandon a further search of the area as deteriorating weather threatened their air support. The searchers spent the night at a base camp they had established earlier at the 5,000-foot level.

On Tuesday, March 25, the morning was clear but the temperature was 10 degrees Fahrenheit and there was a strong 20-knot wind blowing. Snow conditions were becoming unstable, cornices were building, and there was an avalanche nearby. Rescuers recovered the body from a stash site and then were flown from the mountain by helicopter just as visibility began to drop. Although the team was prepared to stay for two days, Sicks estimated it would have taken that long to make the 10-mile trek on winter trails under impossible weather conditions to reach the Dungeness River Road, the only safe exit route.

On Tuesday afternoon, over 800 persons gathered at the McChord base theater for two separate memorial services held to honor the 10 airmen and six sailors who perished in the Starlifter accident.

Difficult Conditions

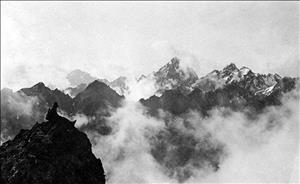

In addition to the volatile spring weather, there had been two minor avalanches at the crash site while the Olympic Mountain Rescue team was there. Olympic National Park’s Chief Ranger, Gordon Boyd, said: “It is extremely steep, hazardous terrain, not only because of avalanche dangers, but because of ice and rotten rock” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). Due to the risk involved, the Air Force postponed further efforts at recovery until after the spring thaw. Boyd said park rangers would monitor conditions around Mount Constance and advise the Air Force when it was safe to allow search parties back into the area. Snow on the mountain was reported to be over 15 feet deep and unstable.

On Friday, May 16, 1975, Captain Douglas McLarty, McChord AFB Public Information Officer, announced that, due to above-average spring temperatures, the wreckage of the Starlifter was beginning to emerge from the snow. A team of two Air Force pararescue specialists and two Olympic National Park Service rangers had been camping on Mount Constance, at the 5,000-foot level, monitoring snow conditions and protecting the integrity of the crash site from interlopers. While there, the men found the body of Airman First Class Robert D. Gaskin, the first since March 24. And on May 29, the team discovered the remains to two more victims, whose bodies were airlifted to McChord AFB for identification.

Finding More Bodies

On Monday, June 2, the official probe into the Starlifter crash was finally officially reopened. Teams of Air Force crash investigators and pararescue climbers were airlifted into the area and set up a base camp at the 5,500-foot level of Mount Constance. The following day, search teams, probing the snow with 10-foot rods, found five more bodies before high winds and a snow storm forced the temporary shutdown of recovery operations.

Although unpredictable spring weather and occasional avalanches continued to hamper recovery efforts, the investigators and search teams made steady progress. The Starlifter’s cockpit and a section of the fuselage, containing several bodies, had been sighted in a snow-filled crevasse approximately 400 feet below the crest of Warrior Peak. The elusive flight data recorder was recovered late Thursday, June 12, and sent to the NTSB in Washington D.C. for evaluation.

On Monday, June 16, Major General Ralph Saunders, commander of the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service and president of the investigations board, announced the Air Force had concluded its investigation into the crash of the Starlifter. The last two bodies had been found and removed from the crash site over the weekend and all the victims were accounted for.

Over the next several days, Air Force personnel, Olympic Mountain Rescue members and Forest Service and National Park Service rangers set about the daunting task of cleaning up the crash site. Army CH-47 Chinook helicopters lifted the large pieces of the aircraft from mountainside, while smaller pieces of debris were collected in cargo nets and flown out. The wreckage was airlifted to the Coast Guard Air Station in Port Angeles and then trucked to McChord AFB for further study and disposal.

Bad Luck, Fatigue, and Inexperience

Although it was clear that the Starlifter’s collision with Mount Constance was the direct result of an incorrect order from the FAA air traffic controller, critics believed other factors could have contributed to the tragedy, including bad luck. Had the aircraft been on a slightly different course or 500 feet higher, it would have missed Mount Constance, the third highest peak in the Olympic Mountain Range. Air Force C-141As were equipped with radar altimeters that should alert the crew when the aircraft falls below a “minimum descent altitude.” However, bad weather, particularly snow, could have rendered the equipment useless.

Crew fatigue was also believed to be a factor contributing to the accident. Although augmented with an extra pilot and navigator, the crew was at the end of a grueling 20-hour day and became complacent, choosing not to challenge the air traffic controller’s direction to descend to 5,000 feet while flying over a range of mountains. En route Low-Altitude Flight Charts, which the pilot uses while flying IFR (instrument flight rules) don’t show terrain heights, but the navigator has access to Tactical Pilotage Charts that do. The pilot should have followed MAC procedures and checked the terrain before accepting the instruction.

The Starlifter’s flight crew, although qualified, was supposedly inexperienced, having fewer than the 1,500 hours of flight time the Air Force considered to be a desirable minimum. As part of Defense Department budget cuts, the Air Force Military Airlift Command had furloughed 25 percent of its most experienced C-141 pilots since January 1975. Forty-four experienced C-141 pilots (18 per cent), assigned to McChord’s 62nd Airlift Wing, had been removed from flight status. As a result, the younger and less-experienced pilots and crew were overworked and under-trained.

In terms of loss of life, the crash of the Air Force C-141A Starlifter remains the biggest tragedy ever to occur in the Olympic Mountains.

U. S. Air Force Casualties:

-

Arensman, Harold D., 25, Second Lieutenant, Irving Texas (copilot)

-

Arnold, Peter J., 25, Staff Sergeant, Rochester, New York (loadmaster)

-

Burns, Ralph W., Jr., 42, Lieutenant Colonel, Aiken, South Carolina (navigator)

-

Campton, James R., 45, Technical Sergeant, Aberdeen, South Dakota (flight engineer)

-

Evans, Earl R., 28, First Lieutenant, Houston, Texas (commander/pilot)

-

Eve, Frank A.,, 27, Captain, Dallas, Texas (copilot)

-

Gaskin, Robert D., 21, Airman First Class, Fremont, Nebraska (loadmaster)

-

Thornton, Richard B., 40, Lieutenant Colonel, Sherman, Texas (navigator)

-

McGarry, Robert G., 37, Master Sergeant, Shrewsbury, Missouri (flight engineer)

-

Lee, Stanley Y., 25, First Lieutenant, Oakland, California (navigator)

U. S. Navy Casualties:

-

Dickson, Donald R., Seaman, Tempe, Arizona (USS Dubuque)

-

Eves, John, Third Class Petty Officer, Ridgewood, New Jersey (USS Dubuque)

-

Fleming, Samuel E., Chief Warrant Officer, Alameda, California (USS Coral Sea)

-

Howard, Terry Wayne, Third Class Petty Officer, Sylmar, California (USS Dubuque)

-

Raymond, William M., First Class Petty Officer, Seattle, Washington (USS Coral Sea)

-

Uptegrove, Edwin Wayne, 35, Lieutenant, Coupeville, Washington (USS Coral Sea)