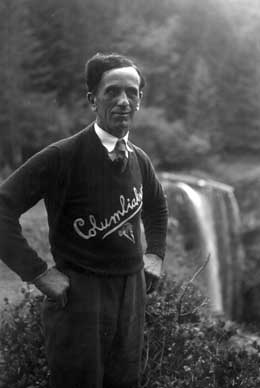

Alfred "Al" Faussett, logger and waterfall-jumping daredevil of Monroe, gained fame for his exploits in the 1920s – when all across the country daredevils were taking on challenges such as going over waterfalls in strange craft, doing stunts on the wings of biplanes, or vying for titles of "the best, the biggest, the only." Al, an inveterate showman, built the innovative canoes and other craft in which he successfully tumbled down waterfalls in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. He competed for attention throughout his life through stunts that achieved fame, but never the riches or happiness he sought.

The Beginning of Ambition

Al Faussett was the eighth of 10 children. He was born on April 12, 1879, to Irish immigrants John (1833-1909) and Annie Faussett (1842-1929). His eldest brother Robert (1862-1943), a self-made man who became Snohomish County's Prosecuting Attorney, wrote of a childhood shanty on a farm in Minnesota with a roof that leaked so badly that "my mother would hold a pan over her in bed to catch the rain" (R. Faussett). From this background in poverty, family members' ambition led to real estate dealings, financial success, and recognition.

The entire family settled in the Monroe area by 1899, following sons who had come earlier for logging jobs. Al was 20 years old and became respected as a tree faller, but it's clear from many entries in his small town's weekly paper, the Monroe Monitor, that he craved attention in other ways as well.

Guy Faussett, his great-grandson, stated that as early as 1901, men "were racing horses from Lewis and Main St. ... their hooves had to touch the river ... and all the way back to town, and Al was always involved in that, and he was a bettor and a gambler” (G. Faussett). In 1902 "he bet that his horse could drag a thousand pounds on a hundred-foot line” (Robertson). Bettors came from all around to compete with Al's horses, or to wrestle, box, and participate in footraces with this cocky young man.

Al was an excellent swimmer, contrary to a commonly held belief based on a misinterpreted news article. On February 20, 1902, he swam to the rescue of his sister, Sarah “Sadie” Beck (1867-1949), and her baby when they were tossed from a horse-drawn buggy as it forded the Sultan River. He also tried to drum up support among men in Snohomish that he could jump off that town's Avenue D bridge and swim the Snohomish River.

The family prospered. In 1900 Robert, who had been educating himself and living apart from the family for years, came to Monroe as the first principal of the Monroe School District and later became Prosecuting Attorney for Snohomish County. Brother Charles (1876-1950) was making a name for himself in real estate, and George (1887-1969), formerly a sawyer, eventually became an interior designer. Al's father passed away in 1909, widely regarded as a wealthy man.

Manhood Brings Domestic Complexity

Al's personal life was complex. After a first marriage in 1903 failed, he tried again in 1908, just a year before his father's death. Vera Schalkaw (1883-1959), of German descent and rigid character, became his bride. Their infant son Earl, born May 5, 1909, died in November of that year. That sad beginning to their marriage did not bode well, although they did have another son, Irvin (1910-1992), the following year. The raising of Irvin was left to Vera, while Al pursued various schemes for increasing wealth. Irvin shared memories with his grandson Guy Faussett (b. 1960), who said, "[Al] was always betting and wild and into something new -- whether auctioning cows or taking off to North Dakota to buy horses. He always had some new scheme ... because he was going to get rich somehow ... He wrecked the family car by jumping it in Monroe one time in a dirt ramp to impress his friends ..." (G. Faussett).

Vera opened her own furniture store in 1919 to provide financial security to the family while Al tried a new scheme to make money in the horse and cattle auction business, but the personality clash of this stern German and her adventurous Irishman was too much. They divorced in 1925.

Daredevil Waterfall Adventures

Only a year later, Faussett was preparing his wildest feat yet, to go over 104-foot Sunset Falls on the Skykomish River and live to tell about it. Guy Faussett stated, “[People] usually say ... that Hollywood was filming a cowboy western movie and wanted somebody to pose as an Indian and go over Sunset Falls in a canoe. It's the most common story ... and absolutely not true” (G. Faussett). A $5,000 offer for exclusive filming rights was mentioned in one pre-event unnamed news article found in the Everett Library's Al Faussett file. However another paper stated after the event, “No deal had been closed with any movie concern and Faussett will derive no funds from that source” (The Everett News, June 1, 1926).

Al's son Irvin told Guy that Faussett, as a logger for most of 20 years, was familiar with Sunset Falls and had heard a story about an Indian who took a canoe over it to prove his love to a woman. With his close friend, steamboat Captain Charles “Cap” Elwell (d. 1947), Al was determined to prove the feat possible.

Together Faussett and Elwell designed the Skykomish Queen, feeling that success would depend more on the boat than on any man riding in it. It was a 32-foot dugout canoe made from a spruce log. Halfway between a long covered rowboat and a kayak in appearance, the craft had a steel front cover to protect from battering on rocks and was fitted with strong vine maple branches that stuck out at angles to deflect the craft from huge boulders.

Faussett hired The Everett News sportswriter Herbert “Scoop” Toole (1898-1928) to be his manager, and together they made sure the public knew well in advance about the event. Ever the showman, Al paraded his boat in Everett and Snohomish to drum up ticket sales, ranging from $1.00 to $5.00 per person for the big day, May 30, 1926. A special Great Northern Railway train was enlisted to carry passengers to the site, and large areas of land were cleared for parking. Newspapers proclaimed the coming event with vigorous hyperbole common to the daredevil fad that swept the 1920s. From Seattle writer A. C. Girard: “Can Al Fausett [sic], prominent logger of Monroe, cheat death in his attempt to shoot Sunset falls next Sunday afternoon? This is the all-absorbing question that is holding the limelight in northwestern Washington. Hundreds say he will never come out alive. ‘Just one chance in a million,’ say some of his staunchest friends, and all the while Faussett is working away making his craft ready for his plunge that will either cover him with glory, or end his life’s chapter” (The Seattle Star, May 27, 1926).

The paper goes on to describe the falls: "a drop of 104 ft. in a distance of 275 ft. with water speed more than 60 mph. Huge saw-logs, 70 ft. in length, shoot over the falls, disappear from sight and come to the surface, completely stripped of bark, their ends shooting skyward, to be hurled from the whirlpool at the base of the canyon” (The Seattle Star, May 27, 1926).

Estimates of the crowd that began arriving on Saturday night for the Sunday afternoon event range from 3,500 to 5,000, and most people avoided the ticket-taker by approaching the riverbank from the surrounding woods. The sheer mass of humanity made ticket collection untenable, even though Al postponed his jump from 1 until 4 p.m., thoroughly angered at the freeloaders.

In the few seconds it took to race through the chute at up to 80 miles per hour, the boat performed as intended. Faussett was deep inside, protected by inflated inner tubes and wearing a patented quick-release belt to fasten him to the canoe. An air tank of his own invention was in place in case he was trapped underwater. The crowd held its breath -- then cheered as the battered boat surfaced at the bottom of the falls. Faussett's own words, quoted in The Everett News the following day, tell the story best:

“People will never know, and little did I dream of the power of those treacherous waters in the falls. When I went under the water hit me with a crushing force and hurt my lungs. It twisted my body and head. I was hurt inside and could not breathe. The line to my air tank had broken with the first meeting of the fast water and I was forced to hold my breath as best I could against the crushing water. The water came so fast it crammed down my nostrils and throat ... . At no time was I afraid of those treacherous falls, not even when the water seemed to be crushing the very life out of me. It was all over in a few seconds, and when I saw the light of day as I rode out of the turbulent waters, I thanked God that I had ridden safely through. Would I ride it again? Yes, I would, but never will I ride Sunset Falls or any other falls unless I see the color of the money first” (The Everett News, May 31, 1926).

Faussett's frustration with the gate-crashers included those who filmed the event. As The Everett News noted, “A battery of moving picture cameras, a number of them having been sneaked in without anyone's knowledge, were on hand to take pictures of the ride” (The Everett News, June 1, 1926).

Despite the loss of money, the thrill of the ride whetted Al’s appetite for more. He immediately began planning to jump 268-foot Snoqualmie and 176-foot Niagara Falls. Much of the summer of 1926 was spent preparing for a Snoqualmie Falls jump, but permission could not be obtained, so Al decided instead to go down 28-foot Eagle Falls, east of Sunset Falls. On Labor Day 1926 Faussett was back on the Skykomish River. Eagle Falls has a much shorter drop than Sunset, but being in a narrower channel, is equally dangerous. For this feat Al built an entirely different craft. Only 16 feet in length, it looked like a big cigar. A hatch on top was designed to close completely, forcing the occupant to lie down inside, unseeing as the wooden cocoon tumbled down the rapids. Iron bands circled the affair, much as the rings on a barrel.

Everett News reporter “Scoop” Toole's friendship with Faussett undoubtedly contributed to that paper’s laudatory coverage. Its brazen headline appeared in one-and-a-half-inch-tall capital letters:

“AL FAUSSETT RIDES FALLS, PERILOUS TRIP MADE IN SAFETY ... On to Snoqualmie and Niagara, says Al Faussett, daredevil logger who successfully ‘shot’ Eagle Falls yesterday afternoon about 2:30 o’clock. A crowd of about 400 Labor Day celebrants witnessed the feat which was considered more dangerous than the trip over Sunset Falls in the Skykomish Queen. The water was low and showed many jagged rocks on the perilous descent but Faussett’s specially constructed canoe made the hazardous trip over the angry looking ‘white water’ without mishap. When half way down Faussett opened up the boat and shouted to his friends on shore. When he landed at the foot of the falls he appeared none the worse for the harrowing experience” (The Everett News, September 7, 1926).

The Everett Daily Herald, lacking the “friend” connection with Al, had a different view of the shout-to-shore incident: “Half way down the dugout wedged in the rocks and remained there until Faussett’s aides on shore came to his assistance with a pike pole. While waiting to be released Faussett opened the protective covering of his craft and called to his friends on shore” (The Everett Daily Herald, September 7, 1926).

Over the next two years Faussett's ambition led him to ever-increasing challenges. On June 1, 1927, he tackled 186 foot Spokane Falls, where he had to be rescued after the first of two rapids. A Spokane reporter wrote, "Dr. Stanley Titus ... said Faussett had sustained a moderate concussion of the brain, numerous contusions of the head and body and possibly internal injuries ..." The writer went on to laud Al's sense of humor and spunk by noting that on his way to the hospital Faussett admonished the ambulance driver to “‘Slow’er up a little, buddy, take it easy an’ be careful. It pays to be careful -- you can't be too careful, no-sir-ee, yuh sure can’t’” (The Spokesman Review, June 3, 1927).

On March 30, 1928, Al went over 42-foot Willamette Falls at Oregon City. This time the hatch of a newer and bigger cigar-design craft didn’t close, leaving Al pummeled, choking, and needing rescue from the pool at the base of the falls. As he recovered in his hotel room after the adventure, discussion was of the tremendous pounding of water on the boat. Al colored the experience with the remark, “Say, if there had been 80 cowbells inside the boat they could not have been heard” (Oregon Journal, April 1, 1928).

The Silver Creek Falls jump was held on July 1, 1928, near Silverton, Oregon. Tumbling down 184 feet, Faussett was nearly killed. He suffered broken ribs, sprained ankles, and numerous bruises. To add insult to injury, his new agent, Keith McCullagh, absconded with nearly $3,000 in gate receipts and betting proceeds, or so it was alleged. The man was said to have left the country. Al’s friends and well-wishers took up a collection to pay the hospital bill for the down-on-his-luck daredevil.

Not all reporters praised Faussett's exploits. After his Silver Creek Falls jump a scathing news article written by Don Upjohn appeared. Titled “Al Improves on God's Handiwork and Plan in Management of Falls,” it decried the mowing of natural vegetation in order to put in parking areas, the barbed wire fencing at the top of the falls, and Al’s control of water flow through the use of a wooden dam, as well as his plan to convert that dam to concrete and put in concession stands.

Faussett considered quitting for a while, but was back at it again, on July 28, 1929, jumping 212-foot Shoshone Falls at Twin Falls, Idaho -- a drop even higher than Niagara Falls in New York. For this challenge, he had designed a cigar-shaped, canvas craft that required him to lie full length inside, surrounded by pneumatic tire tubes. In this inventive protection Al planned also to go over Celilo Falls on the Columbia River and finally, Niagara.

At Celilo Falls, Faussett was approached by Native American fishermen who warned him that the treacherous hidden rock shelves at the base could trap and kill him. They offered him a salmon, "with the remark that ‘if he did not eat another fish before he made the ride, it would be the last fish he ever ate’” (The Everett News, September 19, 1929). He refused the fish, insulting the tribal people, but successfully jumped the 83-foot cataract on Sunday, September 22, 1929, in his canvas craft. This was his last major adventure. (Celilo Falls was destroyed by construction of The Dalles Dam on March 10, 1957.)

Life Out of the Limelight

The daredevil career lasted only a few short years, from 1926 to 1929. Despite increasingly difficult waterfall challenges, Al never hit the financial “big time.” Ticket sales invariably failed to cover the costs involved, and Al’s habit of literally betting his life with those who would win if he died, was not a stable way to riches. He tended to overestimate expected revenues and was generous to a fault, often promising to give to worthy causes a portion of income that was risky at best.

The fame he most sought, going over Snoqualmie and Niagara Falls, eluded him. Despite extraordinary planning since the summer of 1926 for Snoqualmie, dates set, then postponed, he was formally denied permission by Puget Sound Power and Light Company on May 9, 1927 (Associated Press, May 9, 1927). On August 3 of that year in spite of that legal setback, he prepared to jump Upper Snoqualmie Falls. As Faussett approached the rim of the falls, he was served with a restraining order and in frustration, pushed his empty boat over and into the torrent. Publicity leading up to the attempt and the fact that people saw a boat descend, albeit without Faussett inside, may have accounted for the many subsequent news articles that list Snoqualmie Falls as one of his conquests.

In 1929 Faussett went to Hollywood to attempt cliff jumping into the ocean. He lived in Ukiah, California, for several years during the Great Depression with relatives. An undated news clipping in the family album bears the headline “Thrilled Thousands; Now Seeks Wilderness Peace.” It spoke of Faussett’s plans to retire from the daredevil business to become a miner and trapper in the mountains of Northern California. Whether he actually did mine or trap is not known by his family.

By 1934 Al had returned to Portland, Oregon, where he had good friends, and there he remained for the rest of his life. For many years townspeople feted him annually at “Al Faussett Days.” He eked out a living through his mechanical skills. His inventiveness had produced specialized craft for all of his waterfalls, and he knew his tools. There was rarely an auto or old truck that he could not fix for a friend -- not in a proper shop, but by “horse-trading” in his own back yard.

Faussett never remarried, but had many women friends, perhaps the “groupies” of those days. One in particular was labeled only as “Elaine,” and “my better half” on the backs of photographs. She was obviously special, and Guy Faussett would like to talk with anyone who may have known her. Irvin lost all of the family photos and Al’s memorabilia in a house fire in 1959, making images and information concerning Faussett’s life all the more valuable if they could be discovered.

His brother Charles was one of Faussett’s closest friends and hosted him often at his home in Port Angeles, not without some dread regarding Al’s propensity for “glad-handing” and regaling total strangers in restaurants with stories of his past triumphs. Unhappy when out of the limelight, in his 50s Al sought attention through boxing and as a professional ring man and trainer. Guy and Irvin agreed that Al never quite got his fill of appreciation because he felt strong competition within his own family.

Al Faussett died on February 16, 1948, at the age of 68 in Multnomah, Oregon. The Seattle Post Intelligencer proclaimed, “Famed Stuntsman Dies in Bed.” His son Irvin is quoted in this last tribute: “Dad was just nutty about jumping over precipices. He never thought about anything else. Hoped to make the Niagara leap some day, but never got back there” (Seattle Post Intelligencer).

Thwarted in hopes for Niagara for over 20 years, he was building a boat for that attempt in his house right before he died. (Relatives later had to remove part of a wall to get the canoe out.) Great-grandson Guy Faussett feels that Al would be pleased that he is still attracting attention, nearly a century after his exploits.